US-China tech war: rivals no longer worlds apart as they shoot for the moon

- America’s research ecosystem gives it an edge, but those familiar with both countries say it is no longer accurate to bill the rivalry as market vs state

- China’s growing R&D spend is increasingly market-driven as it seeks to incentivise the innovation it craves

“Our market-oriented approach will allow us to prevail against state-directed models that produce waste and disincentivise innovation,” read a White House document in October that unveiled a national strategy to maintain the United States’ global leadership in 20 technological areas, including artificial intelligence (AI), space and medical technologies.

Yet the driving forces behind science and technology advancement in the two countries are not defined precisely by the White House’s categorisation.

02:12

Chang'e 5 returning to China with lunar rock samples

Chinese science policy observers say the rivalry between the two nations is not so much a fight between state-directed and market-oriented models as a race to translate science into commercial applications.

“It has always been a misnomer for people to say the US is market-driven and China is government-driven,” said Denis Fred Simon, professor of China business and technology at Duke’s Fuqua School of Business in the US.

China is becoming more market-oriented with scientists being incentivised to develop technology that can be translated to commercial applications, foreign multinational groups being invited to set up local research and development (R&D) operations, and the government establishing hi-tech parks to spur local entrepreneurship, according to Simon, who has been working in and studying China for four decades.

The country has been the second-highest spender on R&D since 2013 and further closed the gap with the US last year.

Companies (of which state-owned firms contribute 60 per cent of GDP) have in recent years become the main drivers for R&D investment, accounting for 76 per cent of the spending in 2019, while Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Guangdong were among the most committed municipalities and provinces in R&D outlays.

An increasingly decentralised funding model could mean that investment will be better spent, Simon said.

“If you look at the distribution of spending, increasingly the money is coming from provincial and local level, rather than only central government,” he said.

“That’s a good sign. It means those funding these projects are closer to where decisions are being made. There’s more coordination with what’s happening at the local level, which is very important.”

For large-scale undertakings such as aerospace projects, the state-directed approach has long been a trusted Chinese strategy, according to Zhou Yu, professor of geography at Vassar College in New York, who researches globalisation and hi-tech industry in China.

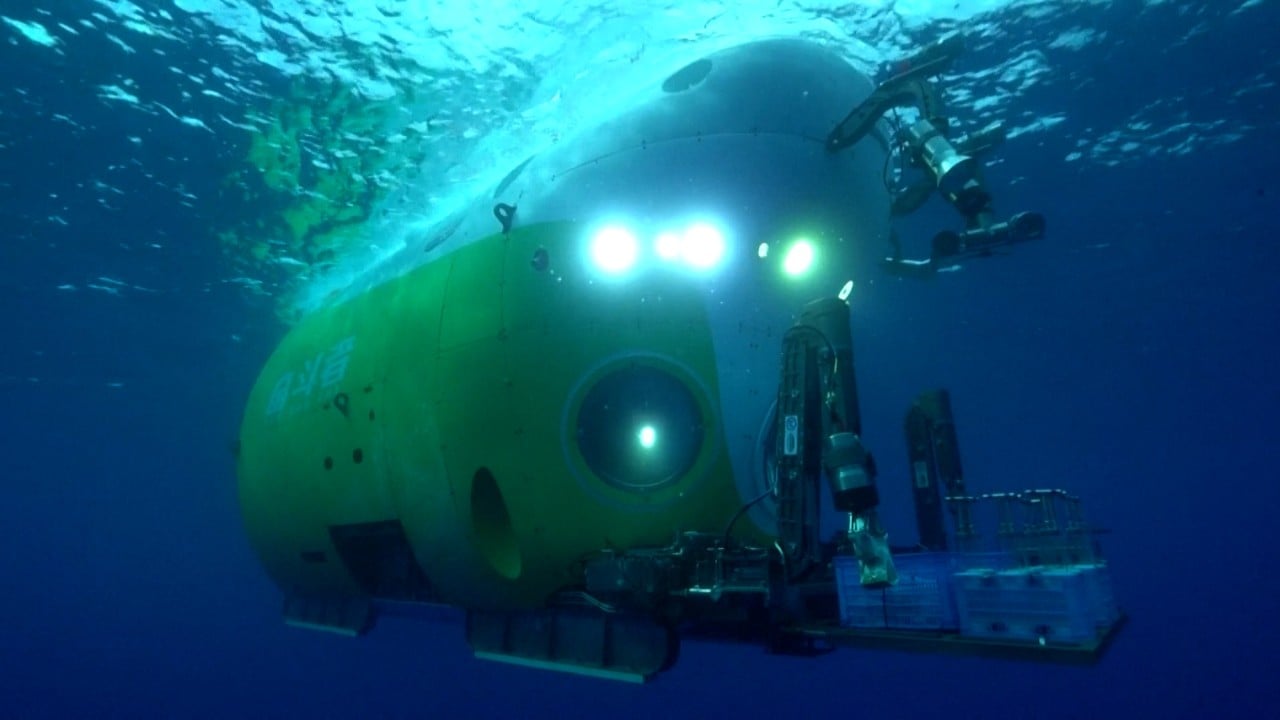

One example is the manned deep-sea diving submersible Fendouzhe, or Striver, which last month extended China’s exploration of the Mariana Trench, the deepest location on Earth.

02:41

Chinese manned deep-sea submersible gets rare look at deepest ocean depths, the Mariana Trench

Development of the three-seater craft, led by state-owned China State Shipbuilding Corporation, involved nearly 1,000 scientists and researchers from about 100 research institutions, colleges and enterprises, including the state-funded Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The 800 million yuan (US$122 million) project started in 2016 as part of a push into deep-sea technology and equipment that had been outlined in the government’s five-year plan ending this year.

But in some industries in China a bottom-up approach is common, such as mobile phone makers working on technology to respond to market demand, according to Zhou.

China’s hi-tech direction for the next five years

Innovation hub Zhongguancun in Beijing is home to 9,000 hi-tech companies, including search engine and AI firm Baidu and social media giant Sina.

The hub’s success cannot be attributed to state policy alone, according to Scott Moore, China programme director at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Zhongguancun emerged partly as a result of conscious planning and policy and partly just because of its proximity to leading universities, much as Boston’s biotech cluster did,” said Moore, the former environment, science, technology and health officer for China at the US state department.

“The distinction between this approach and the more organic one of the West isn’t sharp.”

02:08

China space control juggling with at least three space missions since Chang’e 5 launch

Looking at the US funding model, Cheng Yangyang, a particle physicist and postdoctoral research associate at Cornell University, said the categorisation of state and market-directed approaches was “quite flawed”.

“In the US, since the Second World War, scientific research is primarily government-funded. Not just at universities and national laboratories; private companies also rely extensively on government grants, contracts and subsidies,” Cheng said.

She cited Covid-19 vaccine development and the space industry, and added that major companies sometimes discouraged innovation by pushing out smaller competitors.

“The key issue is whether the development in science and technology is ethical and equitable, whether it advances the public good or serves only elite interests,” she said.

China’s total R&D expenditure by government institutes, universities and companies has grown by double digits for four consecutive years, rising by 12.5 per cent to 2.2 trillion yuan last year, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

R&D as a share of China’s total economic output reached a record high of 2.2 per cent last year, although it remains behind that of the United States, Japan, South Korea and advanced European countries, according to the bureau.

China filed 58,990 international patent applications with the World Intellectual Property Organisation last year, surpassing the US for the first time.

But some experts argue that increased investment did not improve the quality of scientific research.

“[Increased financial input] has obviously raised the quantity of output, so China’s share of scientific publications and patents has soared,” said Erik Baark, professor emeritus at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, who researches China’s science and technology policy.

“However, how efficiently and effectively are these new input resources used? Looking at the level of citations for Chinese publications – which indicate the level of quality and originality of such publications – it is still much lower than publications by scientists in the West.”

Washington’s new strategic technology plan sounds a lot like Beijing’s

Simon, at Duke’s Fuqua School of Business, echoed this, saying that most patents filed were what were known as “junk patents”, which did not have much potential for commercial success.

“Money does not buy innovation,” he said. “You can throw a lot of money in, and you don’t automatically get innovation. This is exactly what happened.

“The inefficiencies in the system, and some of the hurdles, were preventing that extra money from being used efficiently and turning out the kind of innovative results that the leadership was expecting.”

05:20

U.S.-China tech war overshadows ‘phase one’ trade deal

In the next five years, China aims to move towards technological self-sufficiency. Vice-Premier Liu He, President Xi Jinping’s top economic adviser, has said that to achieve this the government is to strengthen R&D capacity, boost international collaboration, do more to nurture research and give corporations a greater role in driving innovation.

Ultimately, countries best able to translate science into practical and commercial applications will have the greatest success in spheres such as biotech and quantum [science], according to Moore, of the University of Pennsylvania.

China vs the US: what are the risks of a space rivalry?

“China has so far not been able to match US translational research capacity, but in fairness few other countries have either,” Moore said.

He said the US had developed an ecosystem in which government technology transfer policies, financing including venture capital, immigration, tax policies and intellectual property protection play important roles.

“We’re collaborating with many countries because it brings us new ideas,” said Yung Kai-leung, chair professor of the department of industrial and systems engineering at Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

“Take this mission as an example: if we only worked with China for moon sampling, we would not have known how it was done,” he said. “Teaming up with scientists around the world expands our horizons on scientific research.”

Can China’s chipmaking drive save it from US embargo?

Simon said China and the US may converge “somewhere down the line” as China becomes more market-oriented in its tech development.

“The last thing I want to see is China running off developing its own separate standards, systems and technologies that are not compatible with those in most of the world,” he said. “It isolates China and creates a certain amount of xenophobia in China.”

He viewed closer collaboration between China and the US as essential to tackling global problems related to science and technology, including climate change, clean energy and water, and global health and pandemics.

“We will not be able to address those in any fruitful way,” Simon said, “unless the US and China can build some bridges and improve their cooperation.”