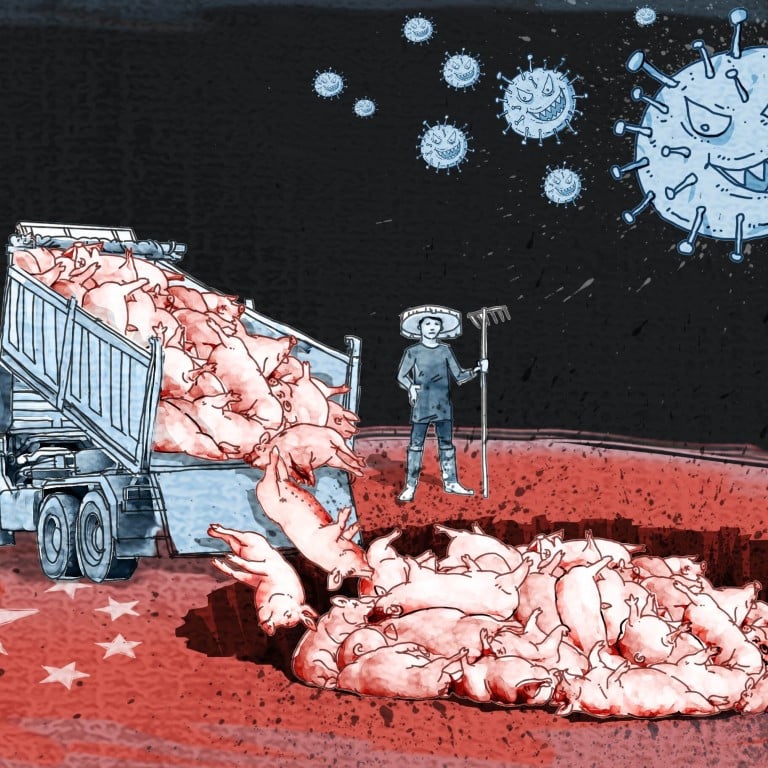

Coronavirus: China will need an army of vets to defend against future pandemics

- A year after the first Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, the country’s animal public health system remains inadequate

- African swine fever exposed inadequacies in 2018 including a lack of qualified vets working in the field

This is the latest story in our series on the Covid-19 pandemic, a year after the first cases were reported in the mainland city of Wuhan. It explores the worrying gaps in China’s animal health services exposed by the new coronavirus, and what can be done to prevent future zoonotic diseases. Please support us on our mission to bring you quality journalism.

What is the status of China’s food security and why is it important?

Covid-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, has taken at least 1.6 million lives, shackled the world economy, and should serve as the definitive warning of the costs of poor animal health, which still loom large for China and the world.

Three quarters of all human diseases have their origins in animal populations, according to the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE).

But, one year on from the first outbreak of Covid-19 in Wuhan, China’s public health system – particularly its animal health component – is still in need of an overhaul, along with an army of better trained, better paid veterinary surgeons, epidemiologists and other public health professionals to prevent the next pandemic.

“It’s absolutely shameful that in a modern society something like this African swine fever thing has been allowed to occur,” said E. Wayne Johnson, a Beijing-based veterinary surgeon and consultant at Enable AgTech.

04:14

Covid-19: coronavirus variants seen in Britain, South Africa spread worldwide

“African swine fever took years to spread from Europe, and through Russia, but it only took a few weeks to spread through all of China,” he said, blaming the rapid spread on poor animal health practices, lax government oversight, and a lack of animal health professionals like veterinary surgeons.

African swine fever is estimated to have cost China 1 trillion yuan (US$153 billion) in economic losses by autumn of 2019 – one year after its detection – according to Li Defa, a professor at China Agricultural University, in interviews with domestic media.

China is still grappling with the disease that killed some 60 per cent of its pig herds and sent pork prices skyward. China’s pig population is recovering, but has only returned to about 88 per cent of pre-outbreak levels, the agriculture ministry said in November.

According to the latest data from the OIE, there are still 20 reported ongoing outbreaks of African swine fever in China in nine different administrative regions.

Game over for China’s wildlife food trade, but does ban go far enough?

Responsibility for public health in China, like in most countries, is shared between multiple government departments, led by the health ministry and Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. The animal health element falls under the agriculture ministry.

China’s top officials are familiar with the connection between animal health and preventing the spread of epidemics.

In June, China’s State Council said its rural health – where most agricultural work is done – was the “weakest link” in the country’s health care system, and called for more veterinary surgeons to work in rural areas for animal disease prevention and control.

Coronavirus, Sars, West Nile virus: how experts plan to stop next outbreak

It was part of a wider call to boost numbers of rural doctors and health workers, whose total numbers have steadily fallen by 3.55 per year for the past five years.

There are only 100,000 certified veterinary surgeons in a country of 1.4 billion people, according to public statistics. Few focus on livestock and even fewer on public health.

In response to the “massive need”, the State Council said it would scrap the requirement for official certification to work as a vet in rural areas. The bar for certification was already set low in China, requiring only an undergraduate degree in veterinary studies, which typically takes three years to complete.

Bat virus? Bioweapon? What the science says about Covid-19 origins

China’s rural veterinary surgeons, on the front line of the fight against animal diseases, are not well paid, despite being in high demand. In December, the city of Gaoping in rural Shanxi province said it would hire 16 veterinary health workers at 2,500 yuan (US$382) per month, slightly less than its residents’ average monthly income.

An investigation by official news agency Xinhua in June showed rural animal health workers near Urumqi in Xinjiang earned just over 1,000 yuan per month – “not even as good as those working in government poverty alleviation factory jobs,” the report commented.

Diana Bell, a conservation and wildlife disease biologist at Britain’s University of East Anglia, said the status of veterinary health professionals needed to be boosted in China. “It’s crucial that these be seen as important, high profile, and good paying jobs, which are there to maintain the health of livestock and the humans that eat them.”

I think it’s an opportunity for China to reinvent itself as a producer of welfare friendly, healthy, organic-bred livestock

Bell studied the origins of the 2003 Sars outbreak, which was also first detected in China’s wet markets. She and her colleagues warned then that a perfect storm of poor animal treatment – including China’s connections to an international illegal wildlife trade and poor health standards in intensive livestock farming – could lead to the creation of a new, more terrifying virus.

And it did.

While much of the origin story of the new coronavirus is still unclear, scientists are sure it made the jump to humans from animals. China placed bans on the human consumption of wildlife in response to suspicions that the virus originated from a nexus of suspected animal hosts, including bats and pangolins.

A team of WHO officials is expected to travel to Wuhan in January to investigate just how the virus jumped.

01:23

China removes pangolin from traditional Chinese medicine list

“I think it’s an opportunity for China to reinvent itself as a producer of welfare friendly, healthy, organic-bred livestock,” Bell said. But she warned that poor health care in China’s intensive livestock farming carried any number of “ticking time bombs” for animal and human health.

Poultry farming has led to different strains of highly virulent bird flu, like H5N1, which killed dozens of people in China over the past decade. Similarly, in the animal population, rabbit haemorrhagic disease was first reported in China in the 1980s, with mortality rates of more than 70 per cent.

“There are millions of viruses out there waiting to be found, and we don’t know whether they are able to be spread to humans,” Bell said.

Animals hunted, traded and homeless host twice as many viruses that infect us

Feng Yonghui, chief analyst at meat industry portal Soozhu.com, said public health and animal health were still largely seen as two separate sets of responsibility in China.

“In China, the main job of the veterinary surgeon industry is to give shots and monitor disease in pigs, cows, chickens and other animals, while public health concerns are left to medical doctors who work on human health,” he said.

“After African swine fever, companies have taken up most of the responsibility for increasing animal health, while the government has maintained its oversight role.”

Feng said few Chinese veterinary surgeons were working in public health, although the exact numbers were unclear. The agriculture ministry did not respond to multiple requests for comment on animal health and public health matters.

Antibiotics created superbug at poultry farms in China, study finds

Finland, by contrast, employs more than 400 local government veterinary surgeons – out of the 2,800 vets in the small northern European country of around 5.5 million people. That is equivalent to one public health vet for every 13,750 people.

In another contrast, Finnish public health vets are not only responsible for animal health, but also public issues like food hygiene.

Dirk Pfeiffer, professor of One Health at City University of Hong Kong, said that while China had made tremendous progress in public health as a developing nation, policy priorities should shift towards a more comprehensive management of human, animal and environmental factors laid out in the “One Health” approach.

06:29

The Hong Kong man who chose to be homeless, and still has no regrets

“While bringing 1.4 billion people out of poverty over the past few decades, prioritising all three human, animal and environmental health at the same time was just not possible in my view,” he said.

Pfeiffer estimated that China only had a few hundred trained veterinary surgeon epidemiologists, and would need to train four to five times its current number over the coming 10 to 20 years.

“Better training in epidemiology will be important,” he said. “There is a need for more future officials working at national and province level to receive specialist veterinary epidemiology training, until every province has a strong epidemiological unit in the animal health service.”