Explainer | What are the coronavirus mRNA vaccines and how do they work?

- Two of the currently available vaccinations against Covid-19 use a relatively new technology which has not been approved before

- Scientists are confident the risks of unintended consequences are low in the short-term

While scientists are confident of their safety in the short term, any long-term side effects are unknown. So what are mRNA vaccines, how do they work and what are their implications for public health?

02:15

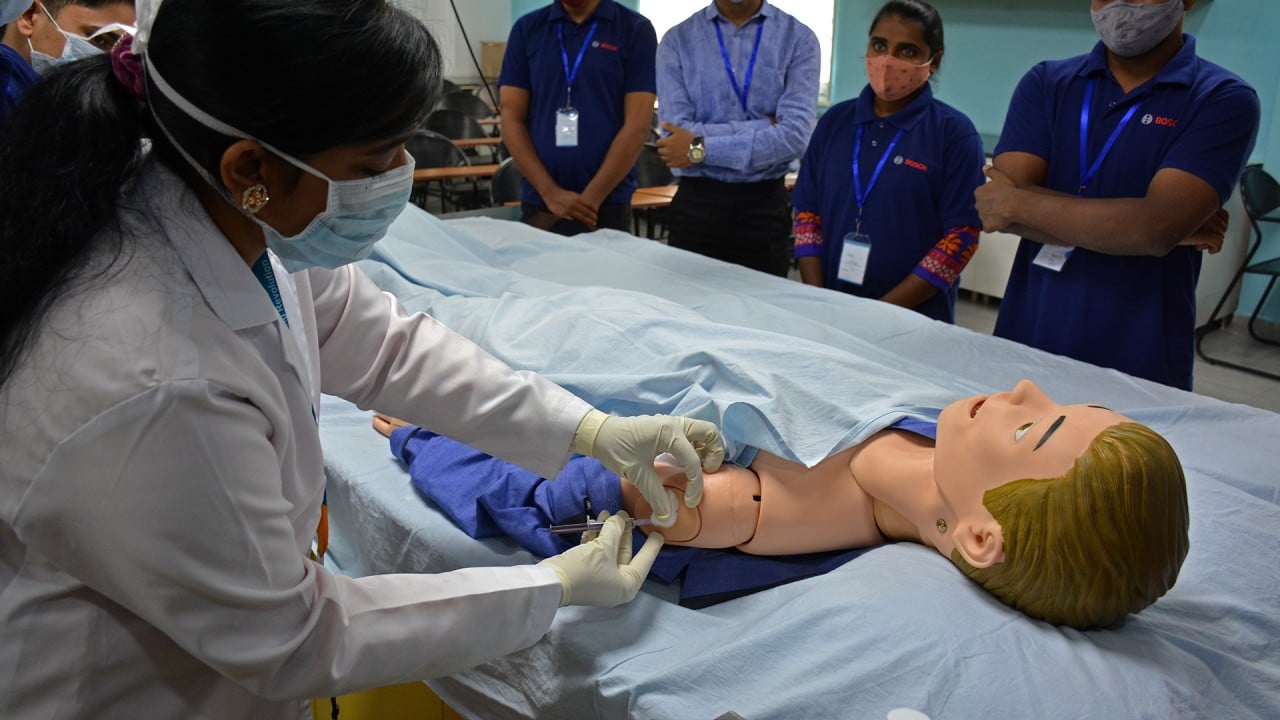

India trains workers to handle Covid-19 mass vaccination programme

Why are mRNA vaccines important?

While expensive to develop, mRNA vaccines can be mass-produced at relatively low cost. They can also be quickly redesigned to cope with a mutation of the virus – a move that has not yet been required, but could be necessary down the track, as shown by the new strain identified in Britain and South Africa.

Traditional vaccines use incomplete, dead or weakened viral strains that are grown in chicken eggs. An mRNA vaccine instead turns the body’s own cells into vaccine factories, triggering a strong, lasting immunity against the virus. It is this feature which makes the mRNA vaccine arguably the most powerful weapon in the fight against Covid-19.

How does it work?

The vaccine works by modifying human cells. It contains no actual part of the virus. Instead, scientists have replicated the genetic instruction – the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) strand – it uses to create its distinctive spike protein.

Coronavirus: scientists keeping close eye on new variant

The spike protein is what the coronavirus uses to invade human cells, so if the immune system can be taught to recognise it – without actually introducing the virus – it can trigger a response and ward off future infection.

The mRNA fragment is wrapped in a fatty parcel that dissolves after vaccination, releasing its information into the body where it will invade any cells it meets. It will instruct the infected cells to produce the spike protein.

This triggers the immune system to attack the modified human cells – because it no longer recognises them – as if they were the Sars-CoV-2 virus which causes Covid-19.

Once the immune system has finished cleaning up all traces of the infected cells, it retains a memory of the spike protein and will go on the attack if it is encountered again. This means that if the actual virus enters the body, the immune system will immediately recognise it and know how to destroy it.

Is mRNA a gene therapy?

The mRNA vaccinations are a form of gene therapy, according to the definition in many parts of the world, including Europe. Few gene therapeutics have been approved by health authorities because of safety concerns, and in most countries they are subject to strict regulation.

Top US scientist Anthony Fauci gets Moderna Covid-19 vaccine

Some patients have died or suffered severe illness due to unexpected consequences of genetic manipulation in other therapies.

What makes the mRNA vaccine different?

Scientists regard the mRNA strand as a relatively safe agent. It occurs commonly in nature and, in simple organisms like viruses, it is relatively unstable and breaks down easily.

This relative fragility means the mRNA fragment used in the vaccine is, in theory, unable to penetrate the nucleus of any cell it encounters, and cannot affect the chromosomes that form the trunk of human DNA.

The risks usually associated with gene therapy – of unintended mutations to human cells which could lead to some cancers and birth defects in the longer term – are therefore believed to be low.

01:55

Coronavirus vaccine: UK grandmother is first person outside trials to get Pfizer Covid-19 shot

What are the short-term side effects?

Most of the various short-term side effects which can follow an mRNA vaccination are simply a sign that the vaccine is working. These can include fevers, chills and muscle soreness and are common symptoms when the immune system is developing its response to any unknown intruder.

A review study by Stefaan de Smedt, professor with the Ghent University in Belgium, found the mRNA vaccine produced symptoms including skin reactions, pain, fatigue, fever and even facial paralysis.

US doctor has allergic reaction to Moderna’s Covid-19 vaccine: report

A major cause of concern was an unexpected immune response in some recipients. In some cases, the vaccine caused a dip instead of a boost to the immune system’s performance, de Smedt said in his review, published last year in the journal Nano Today.

Are there any long-term effects?

Because these vaccines are so new, there is no data on their long-term impacts to human health. The Covid-19 vaccine, as the first mRNA-based therapy, has not been officially approved for use – and the Pfizer and Moderna jabs have both been licensed for emergency use only.

Five stocks lead China’s vaccine race with benchmark-beating runs

However, as of last year, more than a dozen mRNA vaccine candidates for the treatment of diseases ranging from cancer to Ebola had entered clinical trials. None have yet been completed.

What could go wrong in the long-term?

The lack of long-term health data for the mRNA vaccines against Covid-19 has prompted some concern in the research community.

Another type of genetic vaccine – the adeno-associated virus vaccine, which uses a modified version of the target organism – turned out to have a serious problem, long after it was believed to be safe.

Vaccines will save 2021? Not so fast, here’s what the experts think

Dogs vaccinated 10 years ago with an adenovirus vaccine are showing a higher tendency to get cancer, according to a study by a Philadelphia-based team in December last year. Their research suggested the viral genes may have unexpectedly entered the canine body cells’ nuclei and affected the DNA.

Should I take a traditional or mRNA jab?

Proponents of the mRNA vaccines say the technology has been around for 30 years and is theoretically safe. Any serious health issues should already have been detected, through animal experiments or clinical trials.

A massive take-up of mRNA vaccines to fight the Covid-19 pandemic would open a new chapter in medical history, with potential cures using the same method for diseases like influenza, cancer and Aids.

As more Covid-19 vaccines approach the finish line, producers face new hurdles

But critics warn that after decades of research, none of the mRNA vaccine candidates have completed clinical trials. Vaccinating entire countries – or even continents – with a technology that has not been approved for formal use has its risks. The traditional approach may be more expensive or less effective, but has solid data on long term safety, they say.

Which countries are developing mRNA vaccines for Covid-19?

The United States and Germany lead the development of mRNA vaccines. France does not use the technology due to safety concerns, according to the Pasteur Institute. China has placed bets on old and new technologies, by developing five different types of vaccine.

We can’t rule out risks with Covid-19 mRNA vaccines: China health chief

Why has China not approved an mRNA vaccine, even for emergency use?

Gao Fu, head of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, said the mRNA vaccines for Covid-19 were initially developed to treat cancer patients. There would need to be different rules established before this new technology could be applied to healthy people, he said.

“I am not saying there will [definitely] be some side effects in the future, but at the least [the risk] has not been ruled out,” Gao told online news portal ThePaper.cn on Tuesday. “Because it is the first time that humans have used mRNA vaccines on healthy populations, there is a safety issue behind it.”