Coronavirus: unlikely clues to Covid-19 virus family found in Cambodia lab freezer, Thai drain pipe

- Fresh findings expand the range of known coronaviruses related to the one that causes Covid-19

- Researchers look for ‘bat zero’ in the quest to identify the initial animal hosts

“We know these coronaviruses can be found in bats, so it’s not surprising that we found this virus in a bat and it’s not surprising that the virus is very similar to Sars-CoV-2. The surprising part, really, was that it’s from 2010 and that it’s in Cambodia,” said Erik Karlsson, deputy head of the institute’s virology unit.

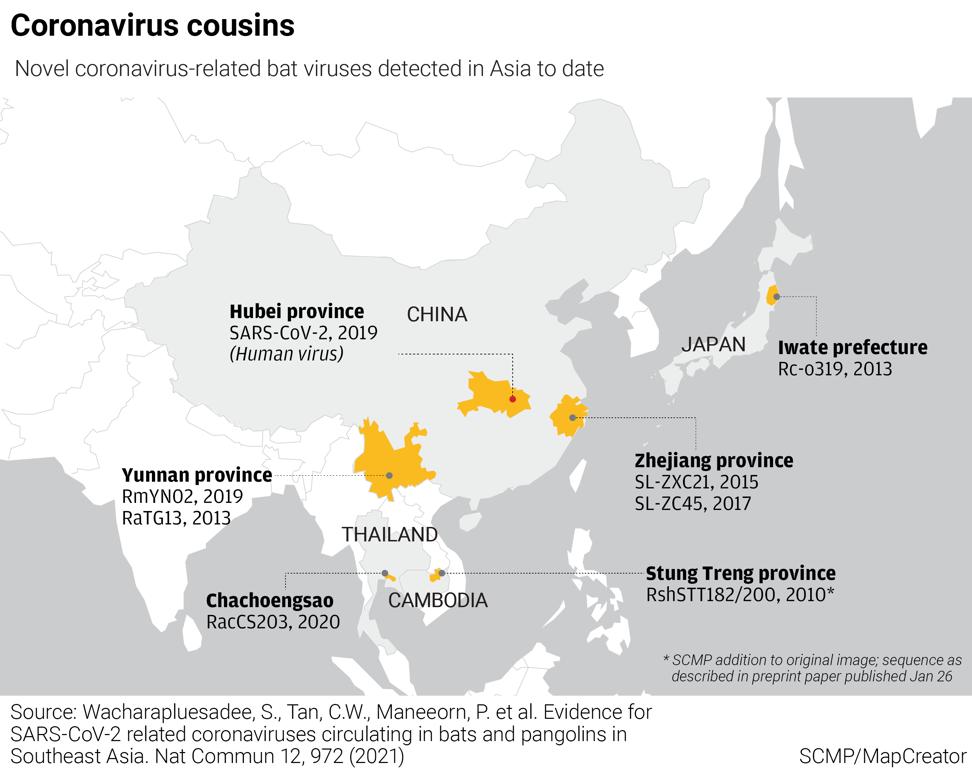

The frozen virus came from a palm-sized horseshoe bat that roosted in a cave near the Mekong River, some 1,130km (700 miles) south of the Chinese cave where the bat virus with the closest genetic similarity to Sars-CoV-2 was found. It’s one of several recent discoveries in Asia, including in bats living in the Thai drainage pipe, that expand the known range of related coronaviruses as scientists hunt for the source of Covid-19.

The suffering and damage caused by the pandemic has focused attention on this search like none other. The World Health Organization repeated scientific consensus that the virus likely came from a bat after a fact-finding team this month concluded a visit to Wuhan, the Chinese city where Covid-19 patients were first identified.

This view surmises the bat virus was likely to have migrated to another animal which then infected humans. But so far no bat or animal virus has been found that is genetically close enough to Sars-CoV-2 to count as a direct relative or immediate ancestor.

The bat link threw another spotlight on Wuhan, or more specifically the Wuhan Institute of Virology, one of the world’s leading laboratories for studying bat coronaviruses. The WHO team said it was “extremely unlikely” that the virus came from an accident or leak at the Wuhan lab, a finding most scientists agree with, although some say a thorough investigation is needed to discount this entirely.

Why more contagious Covid-19 variants are emerging

Supply routes

The WHO team did point to the need to fully investigate supply chains from places shipping farmed wild animals to Wuhan for food.

Some of those are in areas of southern China that have bat populations known to harbour coronaviruses, including Yunnan province, where the two most genetically similar viruses to Sars-CoV-2 have so far been found.

Yunnan borders Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar, and researchers such as those at the Institut Pasteur in Cambodia are separately working to identify related viruses that may lurk in Southeast Asia. The region is considered a hotspot for a branch of coronaviruses such as the one that caused the 2002-03 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), a sister disease of Covid-19.

Their aim is to shed light on the ancestry of the Covid-19 pathogen and others like it to stop another jumping to people.

“We need to understand the family tree for these threats, we need to understand the evolutionary history so we can use that information as background for all the other viruses detected in bats going forward,” said Christine Kreuder Johnson, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California-Davis.

She recently headed Predict, a now finished US government-funded programme that worked with labs around the world to discover viruses and track human infections.

“For us, it’s not so much about going back in time and solving the mystery as much as preparing for the next outbreak or pandemic,” said Johnson, adding that laboratories in the region were going back through bat samples collected in the past to check for related, but undiscovered viruses.

Bat bank

The Institut Pasteur in Cambodia, located in a bustling part of Phnom Penh just down the street from City Hall, employs around 300 staff in five research units and provides medical services to the public, such as vaccination and diagnostic testing.

The virology unit has its own one-storey structure on the campus of yellow and white buildings and flowering gardens. The unit houses the team that screened more than 400 samples collected from bats on field trips and kept in biobank freezers running at minus 80 degrees Celsius.

At first, the researchers thought there might be a mistake when the swab taken from a bat in 2010 revealed the telltale positive sign for Sars-CoV-2 infection: fluorescent lines bending into “s” curves popping up on the monitor connected to their testing machine.

“The first feeling was that there was perhaps contamination there … we needed to make sure before we shouted out about what we found,” said Duong Veasna, head of the virology unit.

But proof came when an affiliated lab sequenced the genome. They found the virus was 92.6 per cent identical to the one that causes Covid-19, making it one of a handful of close relatives and among the first found outside China. But unlike Sars-CoV-2, there was no indication this virus could infect people, the researchers said.

Bat ocean

The result, released last month in a not-yet peer-reviewed paper, came just weeks before another team in neighbouring Thailand published findings from samples taken from 100 bats living in an irrigation pipe in a wildlife sanctuary.

“From that very humble artificial cave in Thailand, with only 100 bats sampled at one point in time, we got important findings,” said co-author and Duke-NUS infectious diseases professor Linfa Wang, who worked with the team of Thai researchers from his base in Singapore.

That Sars connection sparked concentrated research into bat coronaviruses in the country.

“If we applied equal intensity to research in Southeast Asia, I can guarantee we will find many Sars-1 and Sars-2 related viruses, and maybe we can discover [a future] Sars-3 virus in advance,” he said. “We found one virus in Thailand now, but that’s a drop in the ocean.”

Coronaviruses widespread among bats and rats sold for food, study warns

Scary remix

Some 65 million years ago bats developed a trait no other mammal had – the ability to fly.

The skill bombards their bodies with stress and body heat, according to Wang. It also may be part of why bats are such prolific hosts of viruses, which typically infect the animals without harming them.

“For humans we fight very hard, sometimes we die with the virus. Bats, don’t do that, they don’t clear the virus at the level that we do. But bats did not evolve to carry viruses, bats evolved to live with the stress that came with flight,” he said.

Inside a bat, viruses form something akin to a “cloud”, according to the Institut Pasteur’s Karlsson. A mass of coronaviruses – single strands of genetic material that attack cells – are constantly picking up mutations and even swapping parts with viruses around them as they replicate.

“There are segments of these viruses that can mix and mingle with each other, so if you get very similar viruses in any host, they can end up recombining,” Karlsson said.

The viruses bear these traces. In Cambodia, the overall structure of the virus was highly similar to the coronavirus spreading in humans, except for part of its spike protein that attaches to cells. The finding could suggest that this family of viruses has long been spreading in the region and exchanging parts.

“These bats, they don’t live alone, there’s different species sharing the same roost, the same cave, so they do share viruses, especially coronaviruses, and mutations, recombinants happen all the time,” Duong said.

The potential danger in this has been seen before. Wang points to a cave in Yunnan that was monitored for coronaviruses by Chinese researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology for years following the Sars outbreak. Those researchers went back into their own freezers last year and found the closest known virus to Sars-CoV-2.

“That cave, it’s almost like a gene pool, a jigsaw puzzle with pieces of [the Sars virus] all dispersed on different viruses. We’re talking about just one cave, but we found all of the building blocks of the original Sars-1 virus,” Wang said.

“But not in one virus, in different viruses.

“That’s the scary bit of coronaviruses in bats, because these viruses are changing like crazy, and they have all the pieces to form new viruses all the time.”

Bat zero

Picking up the trail of where Sars-CoV-2 started may mean finding these genetic pieces, not just in different bats, but across unknown intermediary animals thought to have played a role in its emergence.

“We may get bits of the genome independently before finding – or never finding – the one that’s closest, because of this recombination,” said evolutionary biologist Eddie Holmes of the University of Sydney in Australia.

Taken together, the latest evidence from Cambodia, Thailand, and another group in Japan who recently discovered a virus in bats that is more distant but still over 80 per cent similar, indicates a wide range of related viruses in Asia.

Understanding where the most similar bat viruses are can help researchers target where to search for traces of infections in humans and other animals.

Where did Covid-19 originate? These virus sleuths are assessing every theory

Wang said it was possible the Sars-CoV-2 bat ancestor virus, or the virus in an intermediate animal, could be in Southeast Asia, where there was greater bat diversity compared with China.

Holmes, however, said the existing evidence suggested the virus originated within China.

“The first cases of this virus are in China, the closest related bat viruses are also still in China, so the most parsimonious explanation for that is the initial spillover took place in China,” he said.

But more work is needed to continue sampling other animals and bats to fill in more data and add to the recent discoveries.

As he puts it: “None of them is ‘bat zero’ yet.”