China-US scientists grow first human-monkey embryo, but is it ethical?

- It’s not in bad taste, says Chinese researcher after injecting human stem cells into macaque embryos to explore possibility of growing organs for transplants

- Most of the embryos died and others grew only low levels of human cells, but the progress achieved leads some to raise fears over where the experiments may lead

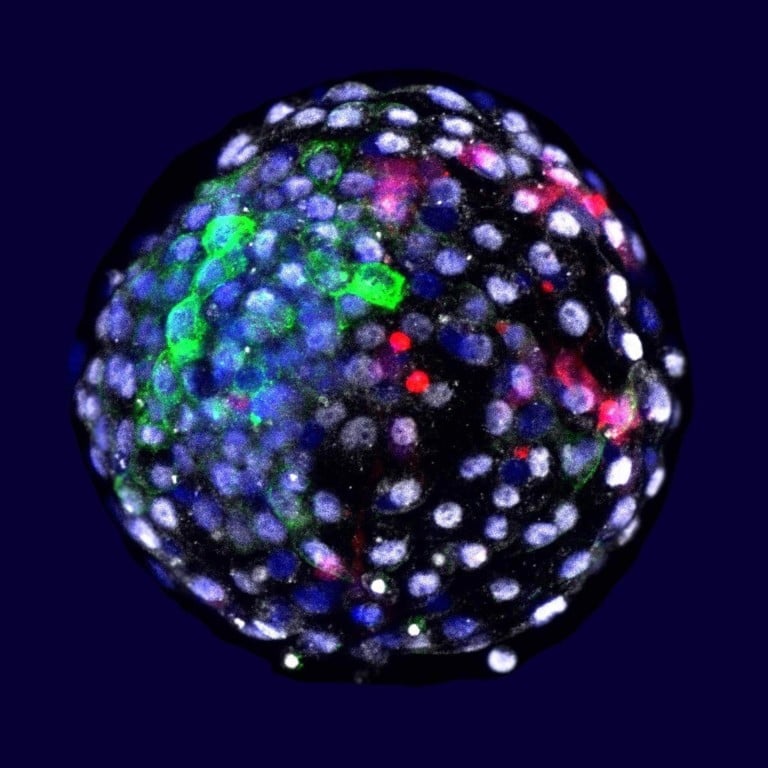

The researchers grew the mixed embryos, or chimeras, in test tubes for up to 20 days, said a paper published on Thursday in the journal Cell.

“This is not a work of bad taste, but [one] of highly practical value,” lead author Tan Tao, of Kunming University of Science and Technology, was quoted by state newspaper China Science Daily as saying on Friday.

But Professor Julian Savulescu, Uehiro Chair in practical ethics at the University of Oxford, said “what looks like a non-human animal may mentally be close to a human”. “This research opens Pandora’s box,” he said in a statement on Thursday.

But the human stem cells did not fare well in monkey embryos, with most embryos dying during the experiment and the few that survived having only 4 to 7 per cent human cells.

In chimera studies, this nonetheless represented progress. Many research teams have grown embryos of animals with human cells. One experiment in 2017 produced 1 per cent human cells in mouse embryos, while in pigs 0.001 per cent human cells was achieved.

Tan’s team believed the monkey embryos did better because they were genetically closer to humans.

Stem cells can grow into various kinds of tissue and organs. Tan and colleagues hoped human-like body parts could one day be developed by animals born with these cells.

More than 2 million people a year are unable to get an organ transplant. “Many people die while waiting, which is very sad,” Tao said.

Most vital human organs can be replaced by transplants, but there is a huge shortage of donors, and compatibility issues. A recipient usually has to take medication to suppress their immune system for the rest of their life.

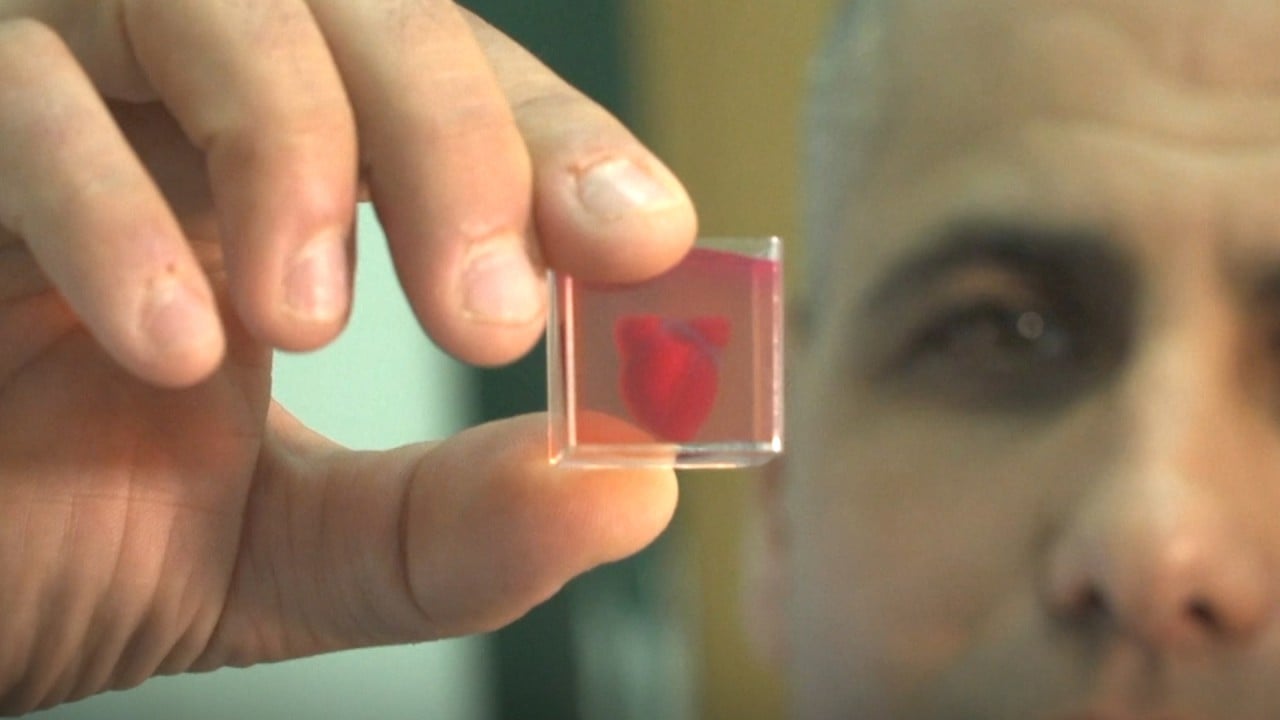

Scientists have proposed various solutions, including tweaking animal genes to reduce their difference from human genes, or using biological 3D printers to make organs from lab-grown cells. But the cheapest way could be to build an organ farm of animals born with human parts.

China’s gene-editing ‘Frankenstein’ jailed for three years in modified baby case

Anna Smajdor, associate professor of practical philosophy with the University of Oslo, said an organ farm would pose significant ethical and legal challenges.

“The scientists behind this research state that these chimeric embryos offer new opportunities … But whether these embryos are human or not is open to question,” she said in a statement.

The human-monkey embryos were destroyed after the experiment, according to Tan’s paper. It remained unclear whether they could develop into a full organism.

“If – and it is a big if – they can create a monkey carrying human cells, it remains highly unlikely its tissues or organs can be immediately used for transplant in humans,” said a Beijing-based life scientist who requested not to be named because of the sensitivity of the issue. “I don’t think it is something urgent to worry about at the moment.”

But Savulescu said such studies could become dangerous. “These embryos were destroyed at 20 days of development, but it is only a matter of time before human-non-human chimeras are successfully developed,” he said. “The key ethical question is: what is the moral status of these novel creatures?”