What is driving China towards its coronavirus vaccination targets?

- The national inoculation campaign got off to a slow start but has picked up speed, with millions getting the shots each day

- Various factors have combined to send members of the public in their droves to vaccination centres

This is the fifth in a series about China’s plans to reopen its borders to the world amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Here, Zhuang Pinghui explores how the goal of inoculating 560 million people by the end of this month has come within reach.

There had been no local cases for months and she usually only left the house to buy groceries from open-air markets – an activity she felt was low-risk enough that mask-wearing was just a formality.

She changed her mind about getting vaccinated weeks later when three residents were infected in a new outbreak in the city. Others felt the same. She went to the vaccination centre three times to get a shot – all to no avail.

“I arrived before 10am each time, but there were at least 500 people ahead of me,” she said. “Some elderly women had been queuing as early as 5am … There were not enough vaccines for everyone.”

Similar scenes played out across the country, with people overcoming their initial reluctance or ambivalence to line up for the jabs. Some even travelled to other cities to get the shots.

That flood of interest is one of the reasons why China is firmly on track to reach the high vaccination rates it needs to reopen the country’s borders.

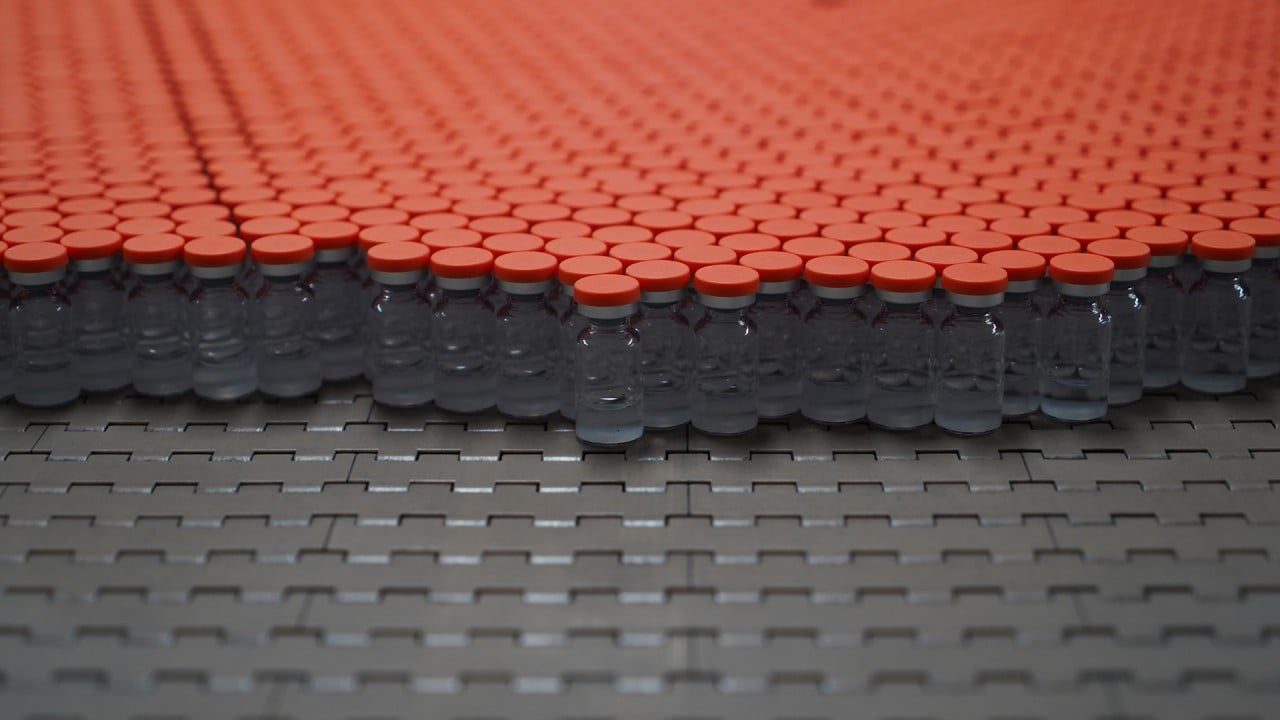

The rate at which China has been able to get shots in arms has risen considerably. It now takes about six days to give doses to 100 million people, compared with about 25 days in the early stages of the mass vaccination programme.

The campaign was slow to get moving in part because of public scepticism about the vaccines. A global vaccine tracking poll by data firm Morning Consult for the week from June 8 found that in China 54 per cent of those interviewed who were uncertain about whether to get the vaccine cited concern about side effects.

Researchers said the high demand for the vaccines did not mean the public no longer had doubts – many had pushed past their concerns because outbreaks in Liaoning, Anhui and Guangdong provinces had dispelled the idea that Covid-19 was completely under control in China.

“There are many drivers for vaccine hesitancy, but an individual’s perception of the threat of the disease is an important one,” said Alex Cook, associate professor of Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, the National University of Singapore. “Outbreaks can bring home the urgency in getting vaccinated, though they will not overcome all the barriers to vaccine acceptance.”

But then came the local outbreaks.

“Vaccination acceptance is high among people who are scared of the coronavirus,” Zhuang said. “People take the jabs after weighing benefits and risks, especially when there is an outbreak going on in Guangzhou.”

Professor Jin Dongyan, a virologist with the University of Hong Kong, said there was still scepticism and reluctance among the population, but Beijing could mobilise its people when it set its mind to it.

“In China if the authorities are determined to have something done, it will be done very successfully. That’s to their credit and also the advantage of their economic social system,” Jin said. “Just like the elimination of [extreme] poverty. It doesn’t matter how they do it, they meet their goal.”

As the deadline for China’s 40 per cent vaccination target looms at the end of the month, local governments in areas where there are no outbreaks – and people are therefore less keen to take the jabs – are offering vaccination incentives.

Cash coupons, cooking oil, cartons of milk, eggs or even tissues have been offered to people to have the two doses. Shops and residential buildings with at least 80 per cent of employees or residents vaccinated are lauded, and some neighbourhoods even publicly honour those aged 60 years or older who have had the jabs.

In other cases, people have been forced to get shots. Even though health authorities have said vaccination should be voluntary, those who work in public institutions, state-owned companies, government agencies or essential services are left with no choice but to take the jabs unless they are medically unfit.

Others who do not get vaccinated can face myriad inconveniences.

Several cities and counties in the northern province of Hebei announced earlier this month that only residents who could prove they had been vaccinated and had not been to an area with Covid-19 cases were allowed into public venues such as hospitals, supermarkets, restaurants and cinemas. “The situation in the world is very severe and the risk of close contacts from high or medium-risk areas coming to the district is very big,” said authorities in Dongqiao district in the city of Zhangjiakou.

Some shopping malls and office buildings in Beijing and Shanghai also tried to limit entry to the vaccinated, although these restrictions were lifted after complaints to authorities.

Coronavirus vaccine: China reports ‘low rates’ of side effects

China’s mobilisation of its population meant it was likely to meet its next goal of vaccinating at least 70 per cent of the total population by the end of the year, Jin said.

It is a contrast to other parts of the region, such as Japan and Hong Kong, which have low take-up rates even though they have ample vaccine supplies.

Khor Swee Kheng, a Malaysian physician specialising in health policies, said the differing outcomes showed the impact of a society’s beliefs, culture, trust in their governments, and historical context.

Japan’s government withdrew recommendations for several vaccines and has been involved in high-profile lawsuits since the 1990s, leading to a mistrust of vaccines that pre-dates the more recent anti-vaccination movement.

Khor said the quality of medical and health services available in both Hong Kong and Japan might also prompt people to see vaccines as less important as a preventive measure.

But Cook, the NUS professor, said there were ways to build public confidence in vaccines.

“Transparency about the risks and benefits of getting vaccinated, including the common and rare side effects, and likewise the risks of not getting vaccinated, helps,” Cook said. “Such transparency obviously needs good data to be available, which has not been the case for some vaccines.”

People also felt more confident when they saw others around them getting vaccinated, he added.

Baruch Fischhoff, professor at Carnegie Mellon University’s Institute for Politics and Strategy and Department of Engineering and Public Policy, said the media also had a role to play in the success of a vaccine programme.

Fischhoff said that in the United States, the federal government had failed to communicate adequately about many aspects of the pandemic, including vaccines.

The standard reporting format from the clinical trials requested by the Food and Drug Agency ensured the basic information about vaccines was available and widely shared, but follow-up communication, such as surrounding temporary suspension of Johnson & Johnson shots over risk of blood clots, was bungled, he said.

“In this situation, the success of the vaccine programme, and many other parts of social response, has depended on our trusted, independent, responsible press,” Fischhoff said. “These are issues that lay people can understand, if the communication is done well. I am very wary of experts and authorities who blame the public, when it is they who have failed the public and not vice versa.”

Back in Shenyang, Li Tinging is still waiting to get her chance to get a dose of a domestic vaccine.

“The vaccines are now all reserved for second doses. I will try my luck in July when they start fresh inoculations again,” Li said.