Now for the big Covid-19 test: how well do vaccines work in the real world?

- All eyes are on whether the shots cut infections and deaths in the face of new variants such as the Delta strain

- Researchers are also keen to see if the jabs can be mixed and matched to improve immune response

A handful of vaccines have passed the World Health Organization’s requirements for more than 50 per cent efficacy and to reduce severe disease and hospitalisation.

China’s zero-tolerance approach helped control Covid-19. Now what?

But scientists are watching to see how well vaccines work in the real world, including how well they reduce the scale and severity of outbreaks in countries with high rates of vaccination.

Jerome Kim, director general of the International Vaccine Institute (IVI) in Seoul, said it was essential to make best use of the existing vaccines.

“We’re trying to move as quickly as we can because the spread of the Delta variant is … a real threat,” he said, adding that real-world research was needed.

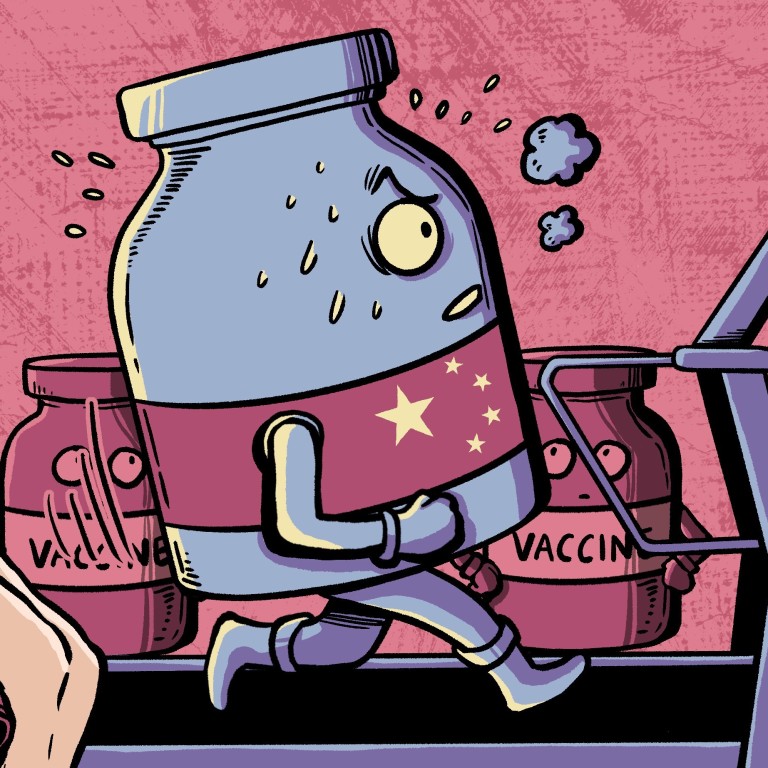

There is less data from countries rolling out two WHO-listed vaccines by Chinese companies Sinovac Biotech and Sinopharm, leaving big questions.

“It’s really important to be able to study these vaccines, like the Sinovac vaccine and the Sinopharm vaccine, extensively in well designed effectiveness studies,” Kim said.

Coronavirus: no certainty on herd immunity until we know more about vaccines and variants

The questions include just how likely vaccinated people are to spread the disease, die, get hospitalised, or get infected, and whether vaccine protection decreases over time or with new variants.

“Every country needs to analyse its numbers, and see if our case numbers are going up, are our deaths going up, are our hospitalisations going up, and are these cases happening in vaccinated or unvaccinated people?” said Dale Fisher, chairman of the WHO’s Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network.

Fisher, also a professor of medicine at the National University of Singapore, said that while it was clear that vaccinated people, regardless of the shot used, could get infected, it was important to understand how severe those infections were.

01:30

WHO approves Sinovac Biotech’s coronavirus vaccine for emergency use

But the trend has not been mirrored by deaths, which have stayed at near zero. In Britain, which has seen more than 20,000 daily cases in recent days, the government is expected to relax disease control restrictions later this month, banking that the high vaccination rate will protect the health system from being overwhelmed by serious cases.

However, reports from elsewhere have raised concerns. In Seychelles, authorities last week reported six deaths among vaccinated doctors, five of whom had taken Covishield, a version of the AstraZeneca vaccine made in India, and one who had been given the Sinopharm shot, according to Bloomberg.

Coronavirus: China’s cities are in a race for herd immunity – but what does that mean?

Dicky Budiman, an Indonesian epidemiologist at Australia’s Griffith University, said more information was needed for a full analysis, but the cases highlighted the need to look at the impact of the Delta variant on the vaccine.

“It raises a very serious concern about the effectiveness of this vaccine against the Delta variant in the real world,” he said. “To a certain degree they are effective, but to what degree, we don’t know yet.”

There is similar uncertainty around the outbreaks in places like Mongolia and Seychelles, which saw spikes after more than half of the population was fully vaccinated, mostly with Sinopharm shots, according to Our World in Data. Deaths rose in both countries, although were still in single or low double digits.

Experts said many factors – from a country’s natural immunity, to disease control measures, more transmissible variants, and vaccine effectiveness – were likely at play but it was impossible to know without details of breakthrough cases.

In Chile, a surge in new infections occurred despite a swift vaccination campaign dominated by Sinovac’s CoronaVac, which is estimated to be about 66 per cent effective there. This outbreak was mainly driven by unvaccinated individuals, according to Eduardo Undurraga, an assistant professor at Pontificia Universidad Católica in Chile.

Coronavirus: global vaccine doses ‘top 3 billion’ as Delta strain spreads

“There is a striking difference in the incidence of Covid, ICU admissions, and deaths between fully vaccinated and unvaccinated people,” Undurraga said, adding there could be various reasons for the outbreak, including pandemic fatigue, inconsistent government messaging, and a premature rollback of health restrictions.

However, CoronaVac’s efficacy could mean that a substantial share of vaccinated people may continue to be infected and transmit the virus, he said.

“While I think it is true that the situation would perhaps be somewhat different with a vaccine with higher efficacy ... it is very difficult for Chile to compete with vaccine demand from high-income Western countries, which have prioritised vaccines with higher efficacy,” he said.

06:18

SCMP Explains: What’s in a Covid-19 vaccine?

Challenges in access to vaccines have become a critical feature of the pandemic, with countries starved of doses as some nations prioritise domestic populations and a WHO fair distribution programme has fallen flat.

Experts said what was critical in the first place was whether the vaccines could protect patients from severe disease. Then the question was whether they could establish a threshold of immunity.

“All of the vaccines that have achieved WHO Emergency Use Listing are highly effective in preventing severe disease and hospitalisation due to Covid-19,” said the WHO, noting that vaccines could not be compared “head to head” given differences in clinical trial design.

Mixing AstraZeneca and Pfizer coronavirus vaccines creates better immune response: study

Of those on the WHO’s list, the mRNA vaccines had the highest efficacy in clinical trials, with the Moderna jabs assessed at 94 per cent and the Pfizer/BioNTech at 95 per cent. Despite being more difficult to store and transport, they appeared to be similarly effective in real-world studies, such as in the US.

A British government study last month found the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine was 96 per cent effective against hospitalisation from the Delta variant after two doses.

AstraZeneca’s genetically modified cold virus vaccine had 63 per cent efficacy against symptomatic infection in clinical trials, while the Johnson & Johnson jab, using similar technology, had 67 per cent efficacy against symptomatic moderate and severe infection.

Recent real-world data from Public Health England indicated that two doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine were 92 per cent effective against hospitalisation due to the Delta variant, while researchers in South Africa, where the Delta and Beta variants dominate, found that among those given Johnson & Johnson’s single-dose shot and who became infected, 4 per cent were moderate cases and only 2 per cent severe.

The Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines use a more traditional technology based on a deactivated Covid-19 virus. Sinopharm reported 79 per cent efficacy against symptomatic Covid-19 in clinical trials of its shot, while Sinovac’s jab was 51 per cent efficacious in a clinical trial in Brazil.

Reports and studies of the inactivated vaccines in the real world also appear to bear out higher levels of protection against hospitalisation. In Chile, a large-scale real world study found the Sinovac vaccine was 66 per cent effective at preventing symptomatic disease, but that protection rose to 85 and 80 per cent for hospitalisations and death respectively.

Chinese firm puts Covid-19 vaccine to landmark test in New Zealand

Protection against hospitalisation was reported as above 90 per cent in government studies earlier this year for Sinovac in Indonesia and Sinopharm in the United Arab Emirates, but there is not yet clear data about real-world effectiveness against the Delta variant.

Without offering details, Feng Zijian of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention said that while vaccinated people fell ill, the rate of severe illness was significantly lower among those who had the shots than those who hadn’t.

02:01

China considers mixing Covid-19 vaccine types to boost effectiveness

Another CDC official, Shao Yiming, said the aim of current vaccines was to prevent mild disease from becoming severe or fatal, rather than completely preventing infection or reducing the ability of infected people to spread the disease.

But just how well vaccines did in reducing infection and transmission could affect the trajectory of the pandemic, experts said.

“If this vaccine makes Covid-19 a mild disease that can still be transmitted, that leaves the path fairly clear that the vaccine is there to protect individuals,” Fisher said, noting that in such a case the virus could largely be manageable for immunised people, but those who were unvaccinated would not necessarily be protected by vaccinated people around them.

While not the focus of clinical trials, there are some signs of the vaccines’ ability to stop people from getting or spreading any infection.

Coronavirus: Indonesia defends use of China’s Sinovac amid surge in Delta variant

For example, vaccination with one dose of either the Pfizer or AstraZeneca vaccine reduced household transmission by up to half, according to a British government study. Meanwhile, multiple studies have shown that mRNA vaccines have high levels of effectiveness at blocking even asymptomatic infection.

Epidemiologist Fiona Russell, a professor at Australia’s University of Melbourne, said the study “suggests an effect on transmission” from Sinovac.

Overall, she said, more information was needed, as “less effective vaccines against transmission will need higher population coverage to prevent transmission”.

A vaccine’s ability to stop the virus from spreading via a level of herd protection also depends on the variants of the virus in circulation. The more transmissible a variant, the greater the proportion of people who need to be vaccinated to see a slowing of spread.

“In terms of achieving herd immunity ... you are really interested in the effect of vaccination against infection,” said epidemiologist Matt Hitchings, from the University of Florida. “If one vaccine is half as effective as another, you are going to need to vaccinate twice as many people to achieve the same reduction in transmission.

“It might get to the point that [achieving herd immunity from vaccination alone] is actually not possible.”

Mixing and matching various vaccines could be another way to boost effectiveness, experts said.

A recent study of Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca suggest that using one of each together could surpass the immune response from the AstraZeneca course alone.

IVI’s Kim supports studies to see if pairing the inactivated vaccines with another kind of vaccine could improve the immune responses to boost protection. Meanwhile, more information was needed on whether booster shots could extend how long vaccines last, he said.

“We don’t know that the protection disappears, but the antibody level is dropping,” Kim said of the inactivated vaccines. “It’s going to be really important for Sinovac and Sinopharm to start publishing the longer term levels of [antibodies] ... for us to be able to understand how quickly the immune responses may disappear.”

The UAE and Bahrain have been offering those who took the Sinopharm vaccine a third shot or a dose of Pfizer after six months, as both countries, which started vaccinations in December, were seeing new waves of infections.

Turkey, where CoronaVac was the first jab to be rolled out, has started to inoculate health workers and people aged 50 and above with a third dose.

Sinovac and Sinopharm executives have said their companies are researching booster doses. The issue was also raised at a National Health Commission briefing last month in Beijing.

“Is it necessary to strengthen immunity? And if it is, how do we strengthen it? This requires us to do more research,” said Wang Huaqing, the China CDC’s chief expert on the immunisation programme.

“Only after we’ve gathered sufficient evidence can we decide.”