Covid-19 drives ‘prevention over cure’ strategy; hinges on global cooperation

- When looking at how to halt future epidemics, the One Health strategy monitors changes in land use, ecological pressure and human population expansion

- ‘Covid taught us that what happens in a small part of the world is everybody’s problem,’ says One Health High-level Expert Panel co-chair

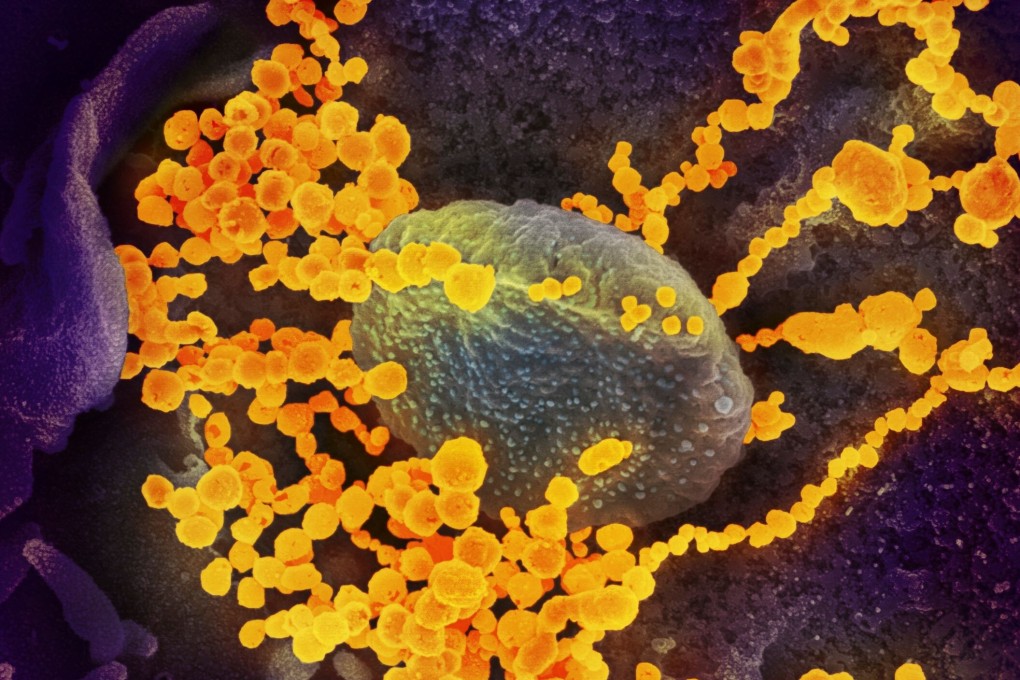

With most diseases stemming from animal origins, human population expansion and deforestation, for example, can create more opportunities for wildlife-borne diseases to infect humans. The added challenge for the One Health approach is a need for international cooperation in a world fractured by political division and suspicion.

One Health was the main theme of the May summit of the World Health Assembly, in which member-states of the WHO make decisions to improve public health. For the first time, the assembly stressed the need for all countries to adopt the One Health approach.

“One Health has always been around, but there wasn’t really an urgency to implement it,” said Wanda Markotter, director of the University of Pretoria’s Centre for Viral Zoonoses, in South Africa. She was named co-chair of the One Health High-level Expert Panel in May.