Explainer | Coronavirus: Did the US fund risky research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology?

- New details about US-financed research in China adds to tensions between Washington and Beijing

- US Senator Rand Paul has repeatedly accused NIAID director Anthony Fauci of lying about US financing for gain of function research

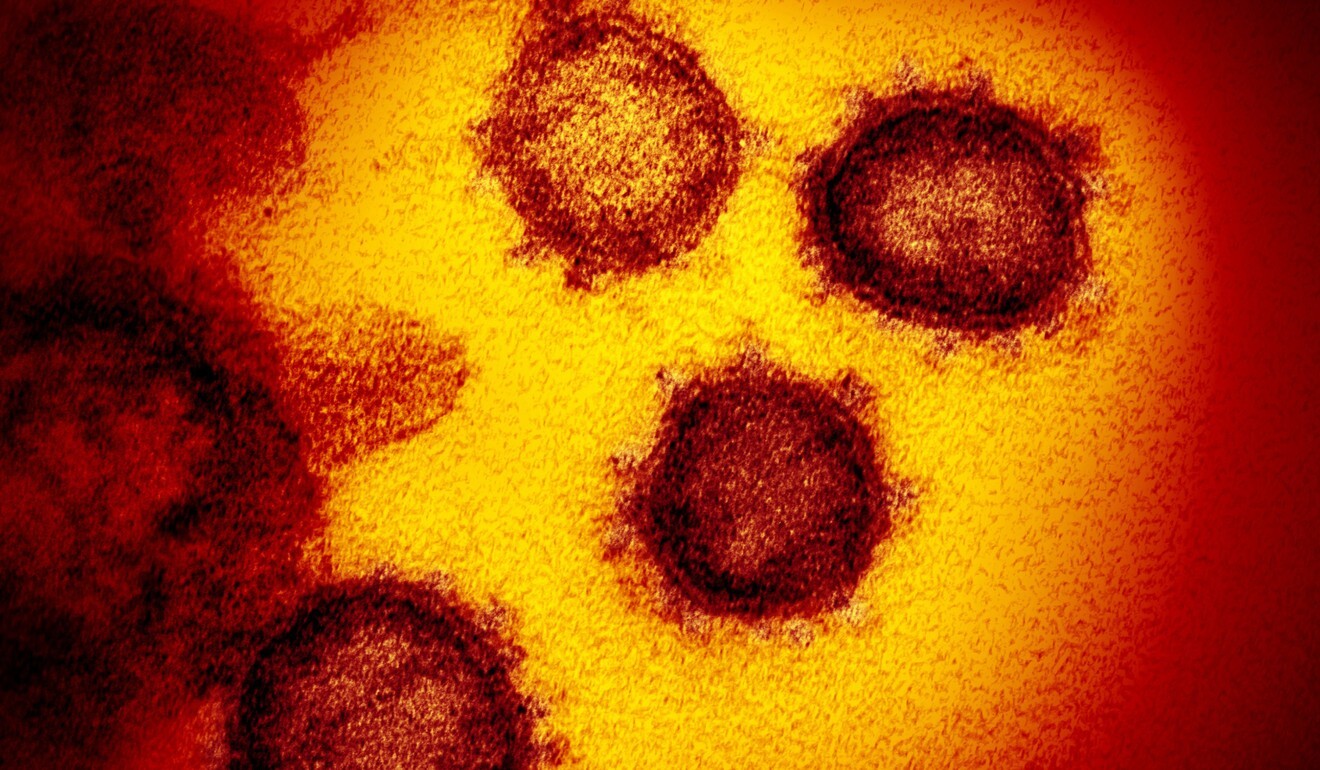

A theory that the Covid-19 pandemic could have been sparked by the escape of a virus from a Chinese laboratory has amped up tensions between Washington and Beijing. It has also raised questions about US funding for bat coronavirus research at a lab at the heart of the controversy.

Among those driving the questions is US Senator Rand Paul, who has repeatedly accused Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), of lying about US financing for gain of function research enhancing bat viruses at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, and suggested that Fauci is complicit in the start of the pandemic.

There is no evidence linking the viruses studied at the institute to the outbreak, and Fauci has repudiated the accusations. Fauci has denied that his agency funded gain of function work at the lab and railed against the senator for what he contends is Paul’s misconstruing of the research and its implications.

Even so, Paul, a Kentucky Republican, upped his claims last week following the release of documents from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) obtained through a freedom of information lawsuit by The Intercept digital news outlet.

The documents, which provide further detail about work undertaken with US financing in Wuhan, have spurred scientific debate about what constitutes gain of function – a broad term that can refer to tightly regulated manipulation of pathogens – and what risks are acceptable in research.

Is there any evidence?

Scientists say none of the known bat viruses handled by the Wuhan institute, including those collected as part of a US-financed project, are genetically close enough to have been modified to become the pandemic virus known as Sars-CoV-2.

The lab, however, has yet to release full records for independent review, and a number of scientists and politicians – as well as the World Health Organization – have called for further examination.

In an evaluation that was concluded last month, most US intelligence agencies also assessed the virus was “probably” not the product of genetic engineering. But they remained divided over whether a lab incident could have played a role in spreading a natural virus.

What US-funded research was conducted at the Wuhan Institute of Virology?

The US-based, non-profit research group EcoHealth Alliance in 2014 received a US$3.1 million, five-year NIH grant to understand the risk of a novel bat virus spilling into humans in China, as had happened in the Sars outbreak in 2002.

“It would have been irresponsible of us if we did not investigate the bat viruses and the serology to see who might have been infected in China,” Fauci, whose institute was responsible for the grant, testified at a congressional hearing in May.

Research was undertaken in partnership with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, with a budget of between US$120,000 and US$150,000 a year under the grant, according to documents released by The Intercept.

Part of the work included exploring whether newly discovered bat viruses had the potential to infect people, and it is this aspect of the research which has come under scrutiny.

Researchers took the spike protein from several recently discovered bat viruses and encoded them onto the “backbone” of another bat virus. They would then see if that new virus was able to infect mice modified to have the same cell receptor as humans.

The work was already public. But a research progress report released for the first time by The Intercept last week indicates there was some change in functionality of these manipulated bat viruses, though scientists disagree about the quality and significance of the data.

One chart in the report suggests these chimeric viruses were initially able to grow better in the humanised mice than the original virus they were built from. Another indicates one new virus caused the mice to have significant weight loss relative to the original.

Was this research gain of function?

In comments to Congress in July, Fauci said the research by EcoHealth “was judged by qualified staff up and down the chain as not being gain of function”. The NIH has also called claims to the contrary “misinformation”, and said “neither NIH nor NIAID have ever approved any grant that would have supported ‘gain of function’ research on coronaviruses that would have increased their transmissibility or lethality for humans”.

Following the release of the latest documents, White House press secretary Jen Psaki backed Fauci and said the NIH “refuted” The Intercept’s reporting that the documents showed the US had funded gain of function work.

The debate about whether the research can be classified as gain of function relates to the generic nature of the term, experts say. It can refer broadly to changes made by scientists to bacteria, viruses or even animals that give them new functionality.

But for the US government, strict controls are warranted for a subset of gain of function research that is “anticipated to enhance the transmissibility or virulence of potential pandemic pathogens, to make them more dangerous to humans”, according to the NIH website.

02:24

Coronavirus: A look inside China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology

“[Fauci] is talking about the [government] definition of ‘gain of function’ of concern, when viruses infecting humans are manipulated to enhance infection, human-to-human transmission, airborne transmission, or virulence,” said Gerald Keusch, associate director of the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory Institute at Boston University.

“Experiments on bat viruses to create chimeras to study molecular mechanisms of infection in vitro or in animal models are not included in that definition,” he said.

The latest information released in the The Intercept documents did not change this, according to Keusch.

“It would be impossible to infer anything about virulence by extrapolating from these data to humans,” he said. “These were bat virus strains, not human coronaviruses.”

‘Inconceivable’ that Covid-19 leaked from lab – Delta proves it, scientist says

Coronavirus researcher Stanley Perlman also said a key distinction for the government view of gain of function was whether experiments would alter the virulence or transmissibility of pathogens in humans.

The recently released charts “tell you how [the viruses] behave in mice and that they are modestly worse in mice than the original virus – but they don’t tell you what would happen in people”, added Perlman, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa.

But virologist Vincent Racaniello, who also attributed Fauci’s position to a difference in definition, said the experiment in Wuhan was “clearly a gain of function experiment because now you have given the [original virus] a new property, which is to cause more weight loss in mice”.

What is the risk of this work?

The Intercept report has stirred debate about whether such research – regardless of how it is classified – is worth the risk, either of creating a new virus that can infect humans or having a lab accident.

For Racaniello, a professor at Columbia University, the benefit of such projects – when undertaken with proper biosafety measures – “far outweighs the risks of these experiments” to understand the potential dangers to humans from viruses in nature.

Keusch agreed: “We can never have enough information about how viruses work and infect their hosts, and you can never know in advance when a finding will have a revolutionary impact on our ability to prevent an outbreak … or prevent or treat illness, complications or death.”

China rejects WHO plans to revisit Covid-19 lab leak theory in new investigation

But Jack Nunberg, director of the Montana Biotechnology Centre at the University of Montana, warned that implanting chimeric viruses into mice with a human cell receptor could cause the virus to adapt to that receptor: “You are setting yourself up for the possibility of selecting for something that transmits better to humans.”

Nunberg said the bat virus research outlined in the EcoHealth grant report did not seem particularly dangerous – given the researchers were using bat, not human viruses – nor did it seem to be a breach of the grant evaluation process.

“Retrospectively you can question, but at the time, it wasn’t someone wanting to … get it more airborne or resurrecting a pandemic strain of flu,” he said. “But any time you make a new virus, you are rolling the dice.”