A journey to the magnetic centre of the Earth – from space

- Zhang Keke heads a team planning to send four satellites into orbit to understand how the planet’s core creates a magnetic field and how the field changes

- The Macau-based planetary physicist has changed continents in the search for an answer

Zhang Keke knew a life-changing opportunity when he saw it.

The planetary physicist had spent decades investigating theories, modelling, and data analyses to try to understand the fundamentals of the planets in the solar system.

The answer to one big question had eluded him and now Chinese space officials were offering him a real shot at finding an answer.

“Would you be interested in doing a satellite project?” one of the officials asked him suddenly at a dinner in Macau in 2019.

Three years later, the project is a reality and the satellites are in final preparations go into orbit on their main mission: to understand how the Earth’s interior generates and maintains a global magnetic field, and how that field changes over time.

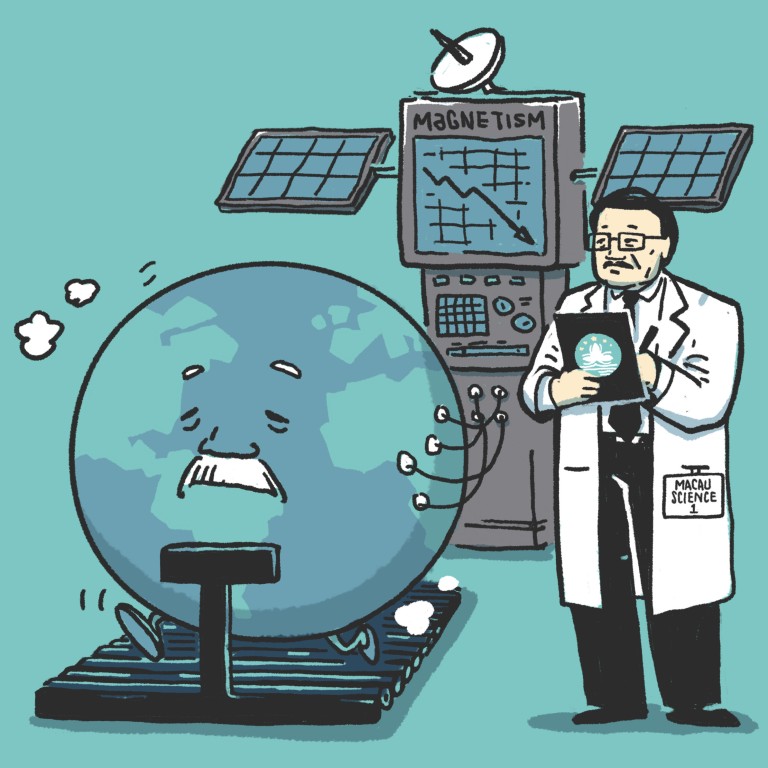

The project is called Macau Science 1 and is based at the State Key Laboratory of Lunar and Planetary Science, or SKLplanets, at Macau University of Science and Technology.

Zhang is the project’s chief scientist and came on board after more than three decades of studying, working and living overseas.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in astronomy from Nanjing University in eastern China about 40 years ago, Zhang went on to earn his PhD in geophysics and space physics from the University of California, Los Angeles.

That was followed by three years of postdoctoral research at the University of Cambridge in Britain and a tenured position at the University of Exeter, where he settled down. “Exeter is a quiet and beautiful town. I love it there,” he said.

His career revolved around the physical properties of planets, both terrestrial and gaseous, with studies into their structure, dynamics, gravity, and magnetic fields.

In the summer of 2018, Zhang was invited to visit Macau and help establish a new research unit: SKLplanets at MUST. When the lab opened that October, it became China’s first state key lab in the field, and Zhang was its founding director.

“At that time I thought everything was part-time,” Zhang recalled.

He continued travelling between Macau and Exeter to meet his commitments but when the coronavirus hit, it became obvious that splitting time between the two places was no longer an option. He had a decision to make.

In 2020, he quit his job at the University of Exeter and joined MUST as a full-time chair professor.

The decision came at some personal financial cost but also offered professional gain – he said that if he had stayed in Britain, he would have had little chance to chair such a big, well-funded and scientifically significant project.

“I lost something, but I also gained something,” Zhang said.

Zhang is now a full-time professor at MUST, leading the satellite project and a young but fast-growing state key laboratory.

After three decades of largely theoretical and analytical work, Zhang is leading his first major engineering project, Macau Science 1, with a total budget of nearly HK$650 million (US$82.8 million).

It involves an initial pair of 500kg (1,100lbs) satellites. When they are up and running, they will be the world’s first and only scientific exploration satellites to study the Earth’s magnetic field and space environment from a low-latitude orbit.

The magnetic field is vital for sustaining life on Earth – without it, the planet would be exposed to strong radiation from the sun and our atmosphere would bleed into space – something scientists believe happened on Mars.

The Earth’s magnetism originates from its extremely hot outer core. As the Earth rotates on its axis, the liquid metal in the outer core flows to generate electric currents and form a magnetic field which extends around the planet.

However, the strength of the magnetic field had dropped by 10 per cent in the past 150 years, Zhang said. The decrease has been especially alarming in the South Atlantic between South America and southwest Africa.

A major goal for Macau Science 1 is to monitor this so-called South Atlantic Anomaly, and use it to look some 3,000km (1,800 miles) into the Earth’s deep interior to see how the Earth’s dynamo works and evolves over time.

With high-quality observation data from Macau Science 1, the hope is that scientists can better understand the reasons and consequences of the Earth’s weakening magnetic field.

The plan is to first send a pair of satellites to a near-equatorial, low-inclination orbit in December, covering the South Atlantic region and other areas near the equator. Then, another pair of satellites will be sent into a near-polar orbit, so that the four of them can form a constellation to have global coverage.

The manufacturing of the satellites has been completed, but tests are still needed to make sure they work properly in space.

“If you are building something to be sent into space and there’s little chance to repair it, you need to make sure every bit of it is done correctly, and everything must be discussed and checked thoroughly,” he said.

New theory challenges origin story on how giant planets found their orbit

Zhang’s team consists of scientists and engineers from around the world. The scientific instruments on board Macau Science 1, including a high-energy particle detector, several star trackers and magnetometers, are partly the result of collaborations with Europe and mainland China.

The team has also signed agreements with 18 research institutions from Europe and the United States to use the satellite data for scientific research.

Before Zhang joined the university, MUST had been involved in China’s lunar exploration programme for about a decade. A small group at MUST worked with researchers at the National Astronomical Observatories in Beijing to do data analyses related to the Chang’e missions.

It grew very fast and was approved to be a key state laboratory in 2018. SKLplanets now has more than a hundred staff members and eight research groups, with research topics ranging from astrobiology to cosmochemistry.

Like other state key labs across China, SKLplanets was set up by the Ministry of Science and Technology. But its funding sources are diverse. Besides the ministry and the China National Space Administration, the laboratory received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Guangdong provincial government and local funding agencies such as the Science and Technology Development Fund and the Macau Foundation, Zhang said.

As the lab’s director, Zhang tries to “make it as scientifically efficient as any lab in Britain or the US”, allowing scientists to do their job independently, and limiting the number of meetings.

The lab’s recruitment is also international, with a number of faculty members from Europe, the US, and Japan.

Zhang said he was happy with the lab’s achievements in the past three years. It is now better equipped and has attracted a number of smart and enthusiastic young people committed to scientific research.

His next goal is to make the lab better known in the region and beyond. “It’s important that people know about our lab. Then they will come visit and work with us.”

In the long run, Zhang hopes to see young colleagues invited to give talks at international conferences and workshops, and shine in the global arena. “Maybe I shouldn’t dream of turning our lab into a world-class one right now,” he said, but his team will work hard to earn wide recognition. “Sometime soon, people will talk about our lab as a good lab – not just good in Macau or China, but in the world.”

Meanwhile there is still a lot of work to do over the next six months to get the satellites off the ground.

Zhang is optimistic but he knows that nothing is guaranteed when it comes to space.

“This will be not just for Macau or China, but for the world,” he said.

“We can only do our best and hope everything works out in the end.”