Shanghai campaign reduced delays in stroke patients getting to hospital, team says

- After the Stroke 120 programme was launched in 2016, median delay time fell from 19 to six hours, according to study

- It aims to educate the public on how to recognise a stroke and to call for an ambulance if there are symptoms

An education campaign in Shanghai has helped to reduce delays in people getting to hospital when they suffer a stroke, highlighting the importance of effective public health messaging, according to the researchers behind it.

The Stroke 120 programme was launched in the city in 2016 to educate the public on how to recognise a stroke and to call for an ambulance if there are symptoms.

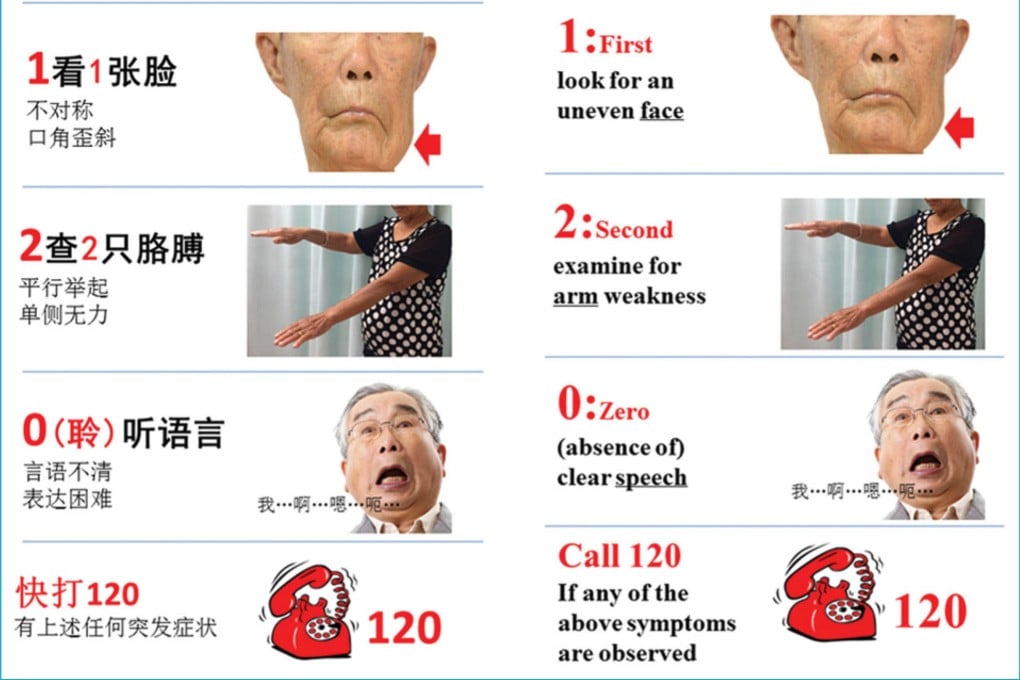

It uses the 120 medical emergency number in China to represent three steps to check for stroke symptoms: 1 is to look for facial asymmetry; 2 is to see if the arms are weak; and 0 – pronounced the same as “listen” in Chinese – is to check if the person can speak clearly.

The campaign involved a one-minute clip broadcast six times a day on local television and radio stations, as well as weekly public talks by doctors and monthly advertisements in newspapers.

“More patients with mild stroke were admitted to the hospital after the campaign, suggesting patients and their family members were more alert to stroke symptoms and sought care even when the symptoms were mild,” the researchers wrote in a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal JAMA Network Open on Tuesday.

They found that the median hospital arrival delay time dropped from 19 to six hours, with one-third of patients arriving within three hours, compared to 6 per cent before the campaign.