China plans to start building first-ever solar power plant in space by 2028

- Orbiting system to be launched in 2028, two years ahead of original plan, scientists say in paper

- Technological advances and potential military applications may have renewed government interest in the concept, researcher says

A satellite will be launched that year to test wireless power transmission technology from space to the ground from an altitude of 400km (250 miles), according to the updated plan in a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Chinese Space Science and Technology on Thursday.

The power generated will reach 10 kilowatts, just enough to meet the needs of a few households.

But the technology could be scaled up significantly and become “an effective contributor to reaching carbon peak and neutrality goals”, Professor Dong Shiwei with the National Key Laboratory of Science and Technology on Space Microwave under the China Academy of Space Technology in Xian said in the paper.

Dong and his colleagues said the plan was first drafted in 2014 and changed in response to “recent technological advancement and new situations at home and abroad”.

The British government said in March that it was considering a £16 billion proposal to put a pilot solar power plant in space by 2035 with the help of various European defence contractors, including Airbus.

The US military has also reportedly tested related technology on the X-37B space plane while considering a US$100 million experiment to power up a remote military outpost as early as 2025.

Nasa, which has shelved the idea for over two decades due to the complexity and cost of the infrastructure, said last month that it was working with the US Air Force on feasibility studies.

A Shanghai-based space scientist with knowledge of the project but not directly involved in it, said the potential military applications, breakthroughs in transport technology such as hypersonic flight, and the push to cut fossil fuel use might have redoubled China’s interest in the field.

In the paper, Dong said the technological challenges of building the first solar power station in space would be unprecedented.

Beaming high-power microwaves over a long distance, for instance, requires an antenna hundreds or even thousands of metres long and any movement from solar winds, gravity or thrusters could significantly reduce energy transmission efficiency and accuracy.

He wrote that other problems included effectively cooling various essential components; assembling very large infrastructure in orbit with multiple launches; penetrating the atmosphere in all weather with high-frequency beams; and preventing damage from asteroids, space debris or a deliberate attack.

Dong said Chinese space scientists and engineers had made some major progress on antenna control and other major challenges in recent years.

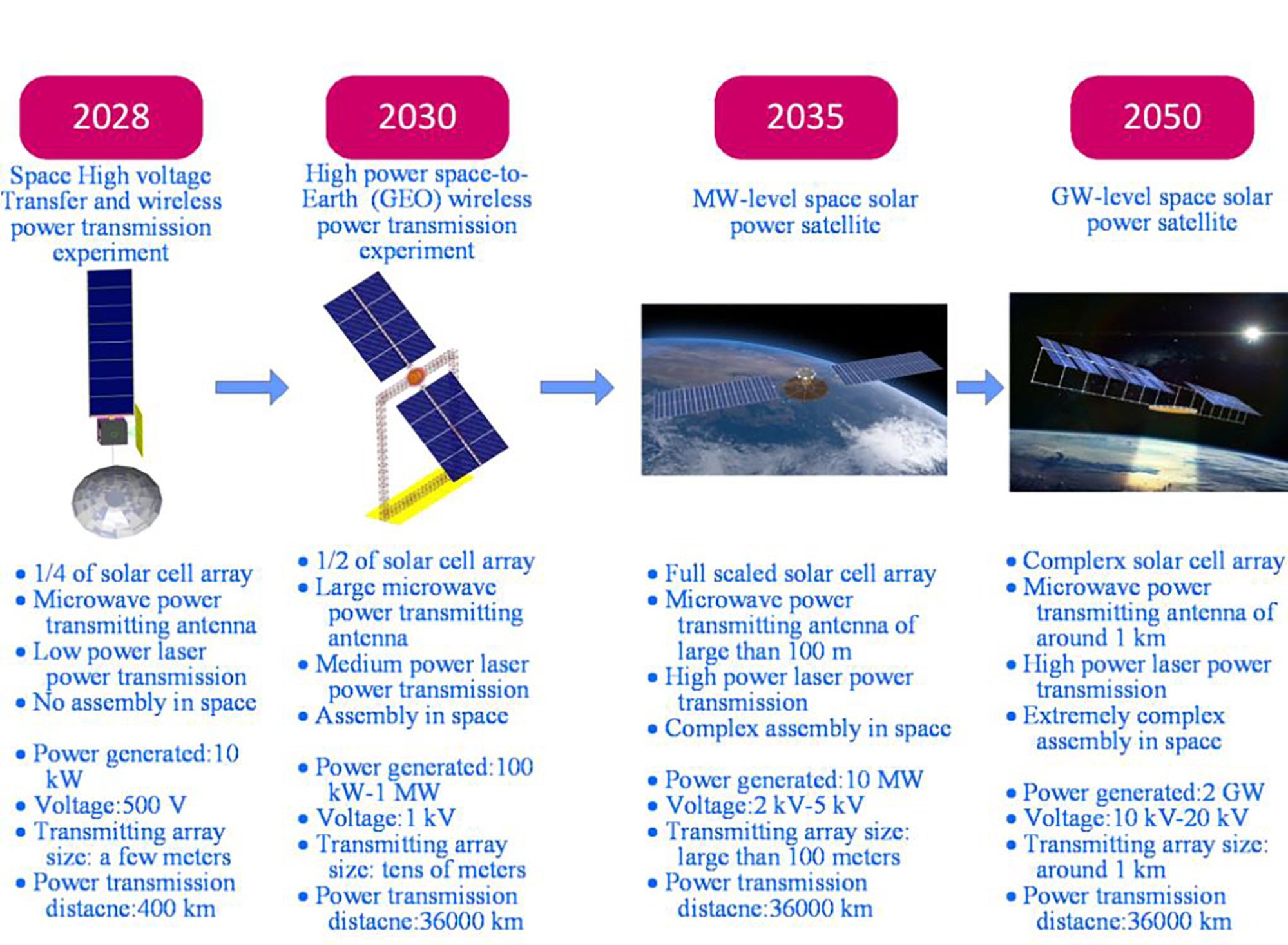

According to the new plan, a full-scale space solar power plant will be built in four stages.

Two years after the first launch, the programme will send another more powerful satellite to a geostationary orbit about 36,000km from the Earth to conduct more experiments.

A 10-megawatt power plant will start sending energy to certain military and civilian users by 2035.

By 2050, the station’s power output is expected to rise to 2 gigawatts, about the same as a nuclear power plant, and the cost reduced to commercially affordable levels.

Dong’s team projected that a full-scale beam could reach 230 watts per square metre on the ground, on a par with direct sunlight. Microwaves at this level are generally believed to be safe for people, but it is unclear what the health effects are for those living close to the receiving station, according to a Beijing-based researcher who studies international law on space activities.

The researcher said space solar farms could operate more efficiently than those on the ground because they could generate electricity around the clock, but “such huge infrastructure in space could make many countries uncomfortable, especially those without the technology or capacity to build one”.

High-power microwaves or lasers can also jam communications technology or damage hardware as a directed energy weapon.

Some defence scientists have proposed using space solar power technology as a weapon of mass destruction that can target a city or manipulate weather.

“There is currently no international law to regulate these activities,” the researcher said.