Why do giraffes have long necks? It could have been to fight for mates

- Scientists have puzzled over how the mammals got their necks – it’s commonly believed evolution was driven by competition for food

- But an analysis of fossils from 17 million years ago suggests early ancestor’s fierce headbutting was ‘likely the primary driving force’

Giraffes may have evolved long necks to fight with rival males for mates, according to an analysis of fossils from an early ancestor of the mammal dating back 17 million years.

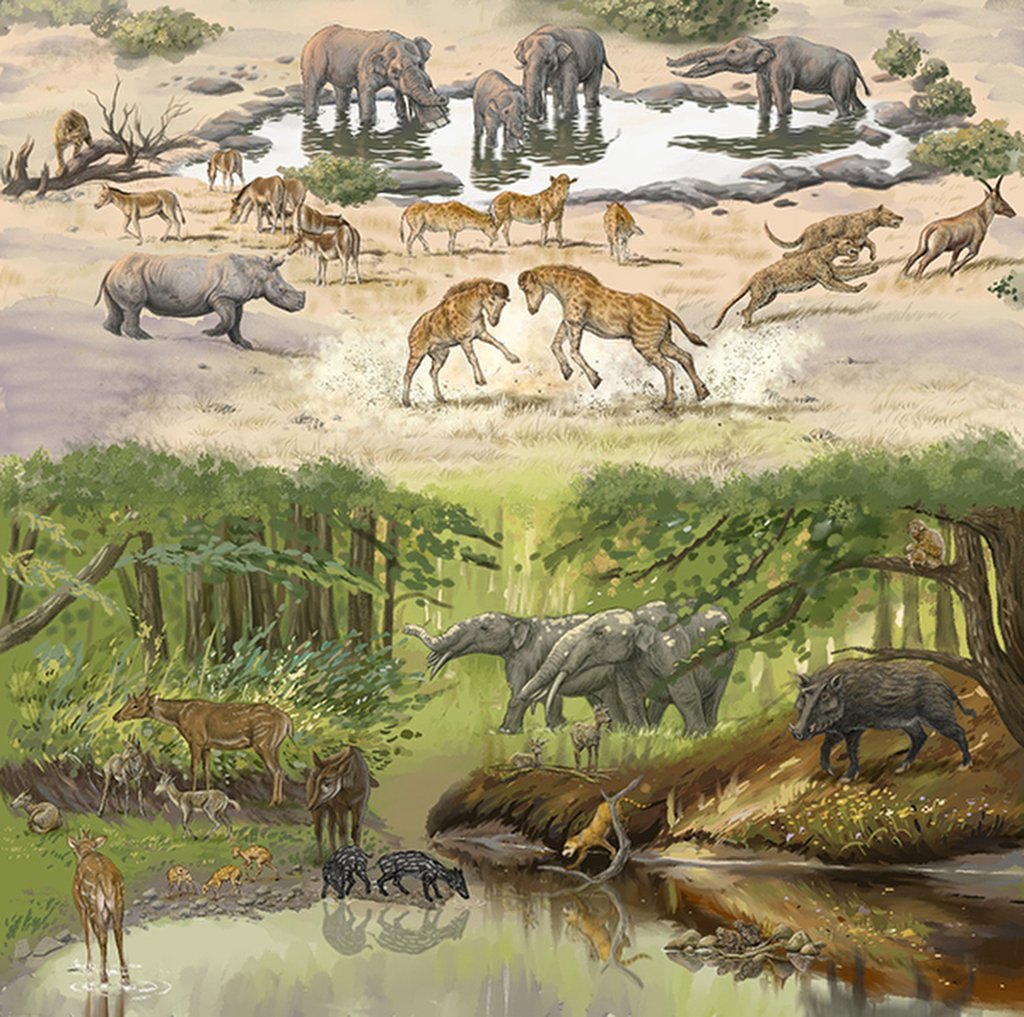

Just how giraffes evolved their long necks has long puzzled scientists. It is commonly believed that it was driven by competition for food – allowing the tallest land animal to access treetop leaves in the African savannah woodlands well outside the reach of other ruminants.

But fossils from the ancient giraffoid species, found in China, had helmet-like headgear “possibly for use as a weapon in intraspecific male competition”, according to an international team led by researchers from the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

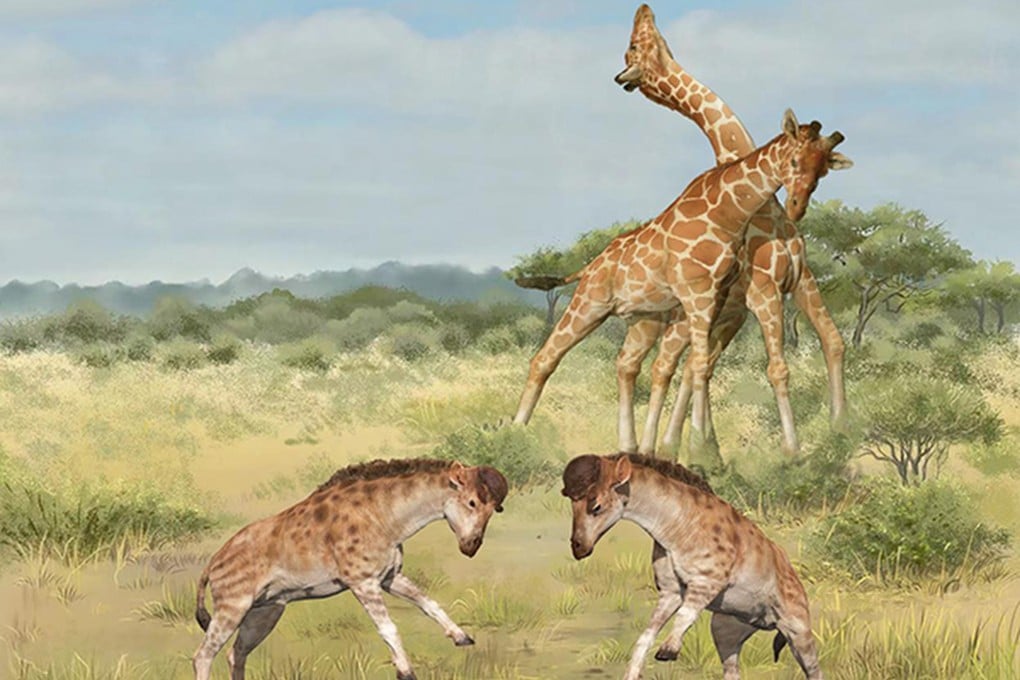

“[The newly discovered giraffoid] had a distinctive disk-like headgear combined with a complex head-neck morphology suggesting that it performed fierce headbutting behaviour,” they wrote in an article published in the journal Science last week.

“‘Necking’ combat was likely the primary driving force for giraffes that have evolved a long neck, and high-level browsing was likely a compatible benefit of this evolution,” the team from Austria, China, Germany and the United States said.

That combat involved hurling their rock-solid skulls by swinging their necks – 2 to 3 metres (6.5 to 9.8 ft) long – against the weak points of challengers, the researchers said. The longer the neck, the greater the damage to the opponent.

Present-day adult males usually grow to between 4.6 and 5.5 metres, and giraffes have seven neck vertebrae – the same as humans and other mammals.