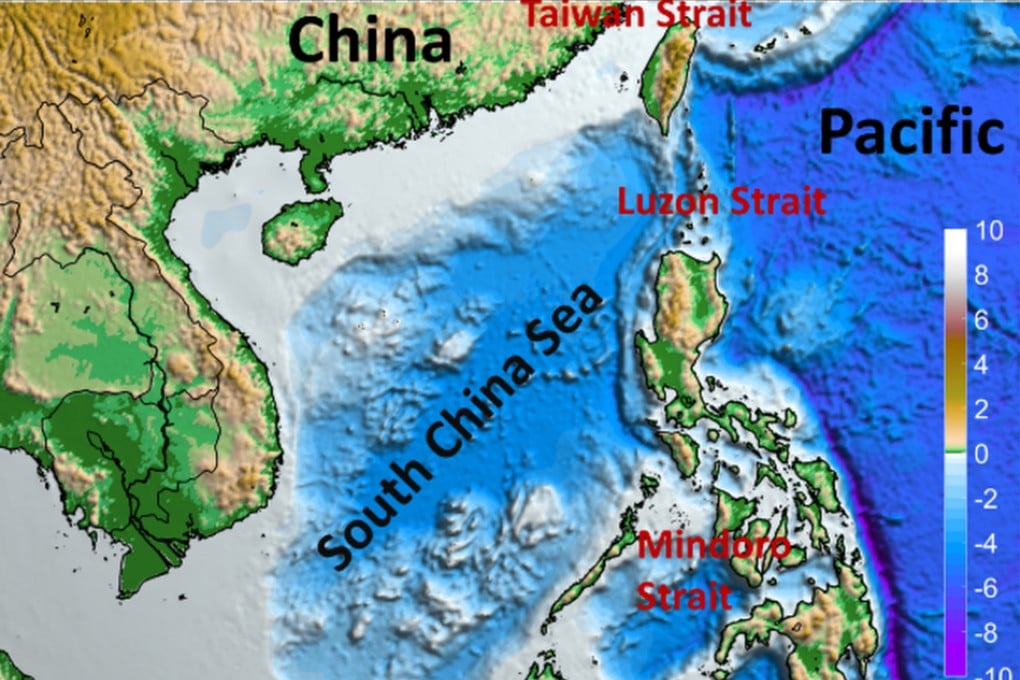

Scientists unravel structure of ocean currents in the South China Sea

- Three-layered rotating circulation is key to monitoring climate change, fish productivity and other areas

- The sea is surrounded by countries that are home to around 22 per cent of the world’s population

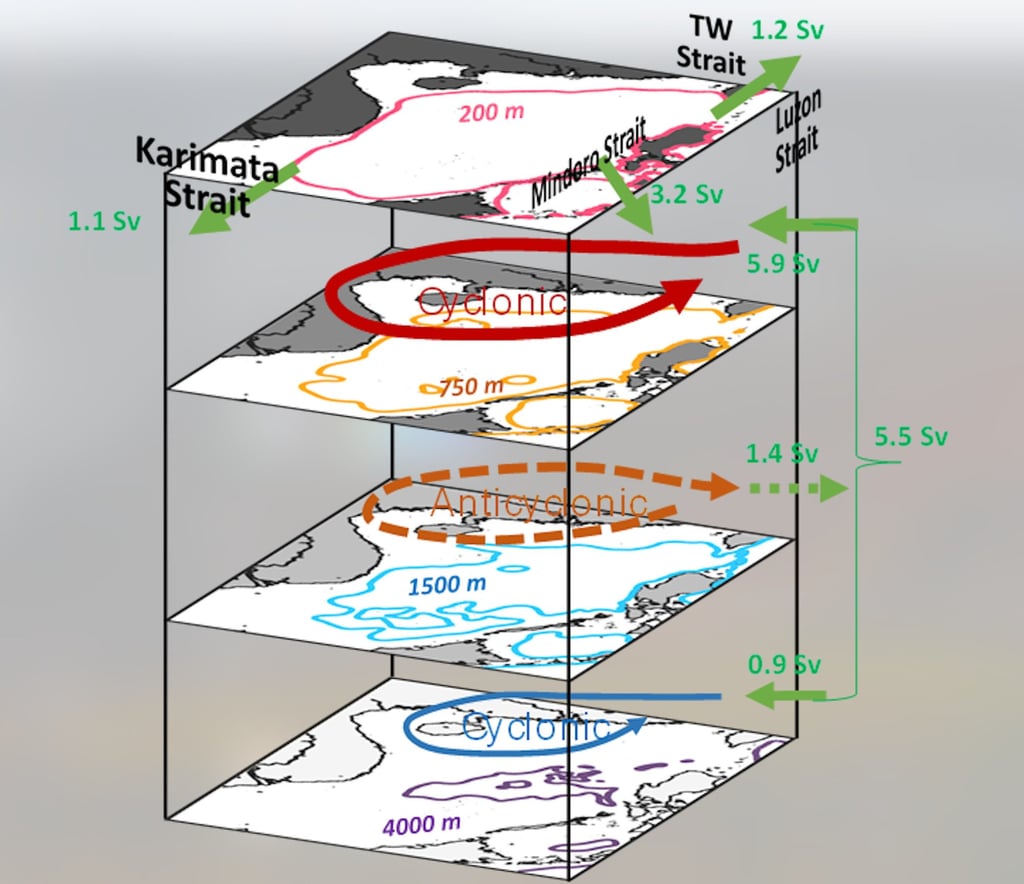

Led by Gan Jianping from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, the team found a three-layered structure of rotating circulation in the sea. They discovered the currents rotate anticlockwise in the upper layer, clockwise in the middle layer, and counterclockwise again in the bottom layer.

Rotating horizontally, the currents cause corresponding upward and downward motions, according to the researchers. The upward motion brings nutrient-rich cooler, deep water towards the surface, providing food for marine life. The downward motion deposits and spreads organic carbon into the deep ocean.

Study lead author Gan, a chair professor who specialises in ocean circulation research, said changes in ocean currents had a big impact on biological productivity – and in turn fishery – in the sea.

“Taking fishery as an example, if the rotating current becomes weaker – such as under climate change – less nutrients will be brought up to the surface and fish productivity will drop,” he said. “That means there will be less fish available to feed countries surrounding the South China Sea such as China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.”

The researchers from HKUST, the University of Macau and the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen published their findings in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications in April.

“This three-dimensional circulation has a profound influence on pathways of water mass path and the transports of energy and biogeochemical substances in the [South China Sea],” the team wrote.