Asteroid’s ‘unique trajectory’ created world’s longest meteorite field in China

- Aletai likely entered atmosphere at a low angle and followed a path like a stone skipping across a lake, according to international team of scientists

- It is not known when the iron meteor shower took place, but fragments are scattered across a vast expanse of more than 400km in the Xinjiang region

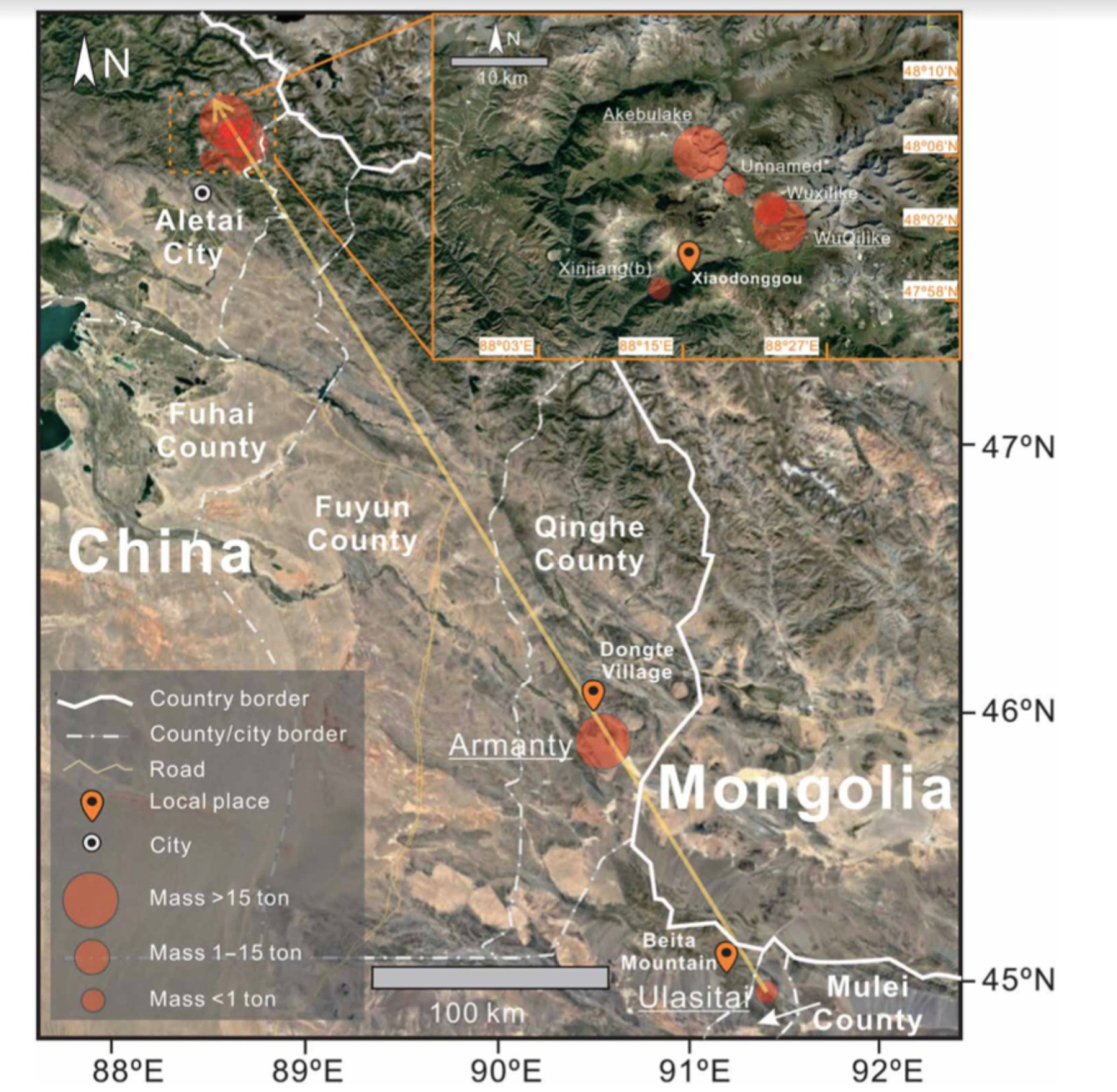

Fragments – some weighing 20 tonnes and some just tens of kilograms – were scattered across a vast expanse that spans some 430km (267 miles), the longest known meteorite field. It was unlike anything scientists had seen before; meteorites from the same “parent body” usually end up no more than 30km to 40km apart.

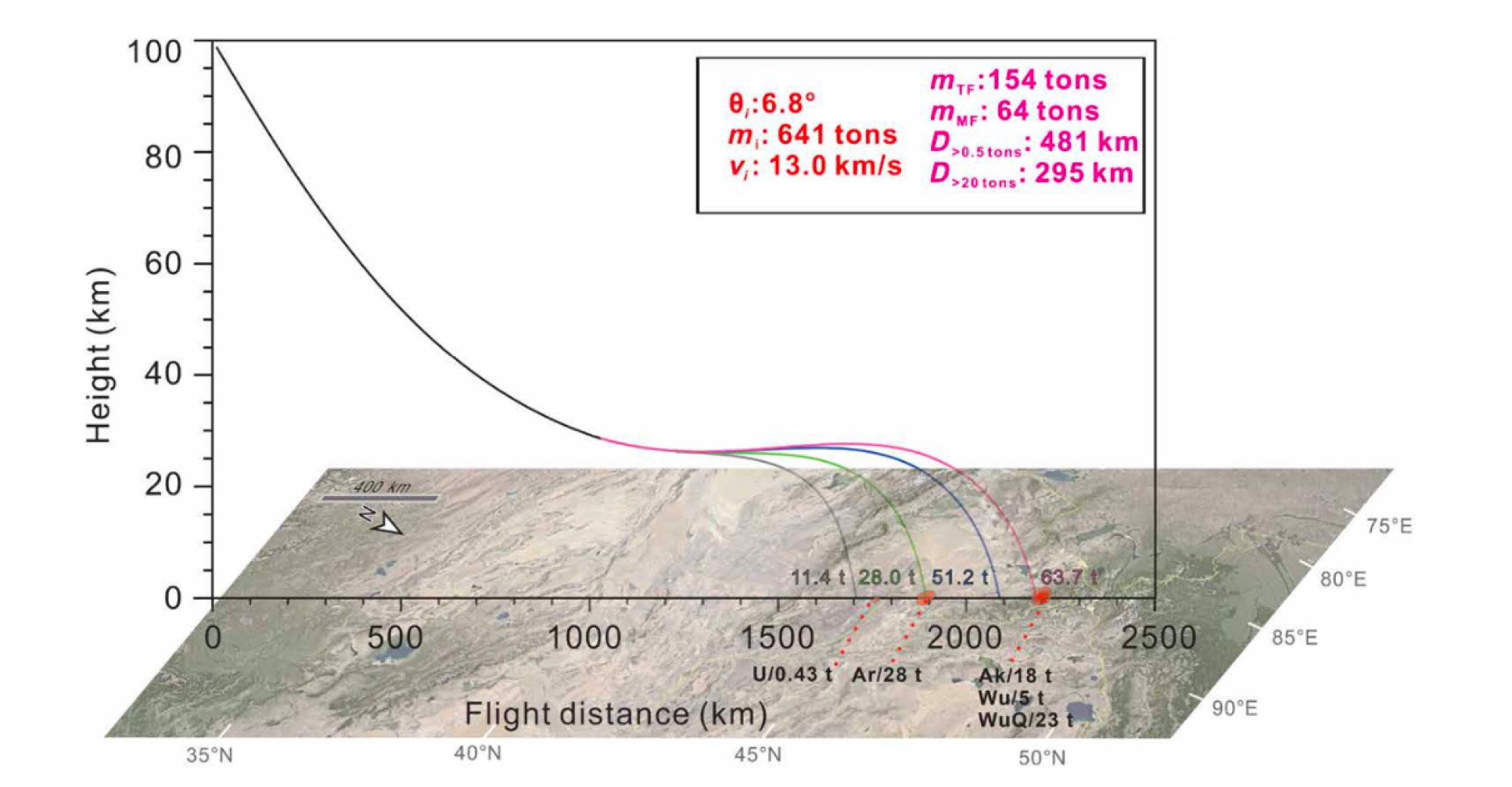

Using numerical modelling, an international team of scientists have now found that the asteroid – known as Aletai, the Mandarin name for the area – probably entered the atmosphere at a low angle and followed a path like a stone skipping across a lake before hitting the ground.

They reported their findings in the journal Science Advances last week.

“It’s the first time such a unique trajectory has been identified,” said Thomas Smith from the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, who was not involved in the research.

“The trajectory explained why asteroid Aletai has the longest known ‘strewn field’, which is an ellipse-shaped area where meteorites from a single fall are found.”

It could also explain why the meteorites did not make craters on impact with the ground, as energy dissipated during the long-distance flight, Smith added.

The results of the study could help scientists better assess the potential impact and risk posed by asteroids, based on its trajectory through space. It also sheds light on where more Aletai meteorites could be found.

Researchers from mainland China, Macau, the United States and Europe used different combinations of initial mass, speed and entry angle to simulate the asteroid’s trajectory.

They found that Aletai was 2.1 to 4.7 metres wide and weighed more than 200 tonnes. Travelling at 12 to 15km/s, it penetrated the Earth’s atmosphere from an angle of between 6.5 and 7.3 degrees.

“The entry angle is crucial,” the paper’s co-author, Hsu Weibiao from the Purple Mountain Observatory in Nanjing, told the official Science and Technology Daily.

“Had it been steeper or flatter, the asteroid would have either smashed from above to form a much shorter strewn field, or bounced back to outer space.”

Smith, who has studied meteorites in Europe and China, said Aletai was significant, partly because it represented a small group of iron meteorites known as IIIE.

There are only 16 specimens in the group and they contain haxonite – a hard white mineral that makes it extremely challenging to cut through an IIIE iron meteorite.

So far, more than 74 tonnes of Aletai meteorites have been recovered. The largest – discovered by a farmer in a trench in 1898 – weighs 28 tonnes.

More iron meteorites have been found in the area in recent years since 2004, but scientists initially did not realise they belonged to the same asteroid. It was not until 2015 that the dots were connected, when Hsu and his colleagues compared the mineral composition and trace elements in three of the largest pieces. They found the fragments shared similarities and the iron meteorites were renamed as Aletai.

The study of Aletai meteorites is far from complete. For instance, it is not known when the meteor shower took place. “The ‘terrestrial age’ of Aletai meteorites may be relatively short and difficult to quantify in the lab,” Smith said.

Authors of the study also said their modelling results could change as new Aletai meteorites are recovered in the future.