Chinese scientists develop new ‘controllable and reversible’ gene-editing technique

- Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Scientists say their technology uses an enzyme that targets RNA and has more short-lived effects

- The team says the technique could prove more efficient and safe and appears not to cause collateral damage to non-target cells

Chinese researchers say they have developed a new gene-editing tool that is more efficient and safer because it does not permanently change the genome.

The most widely used system employs CRISPR-associated protein-9 (Cas9), an enzyme that can cut the two strands of DNA in the genome to add or remove material.

But the new approach uses the Cas13 enzyme, which targets RNA. The technique is believed to be safer since RNAs are transient molecules that only exist in the cell for a limited period of time and are not integrated into the genome.

“Compared to DNA editing techniques, the Cas13 gene editing system is safer, and the effects are more controllable and short-lived,” Yang Hui, the corresponding author of the study and a researcher at the CAS Centre for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology, said.

“CRISPR-Cas9 and Cas9-based gene editing tools are well protected by patents. Other companies don’t have a chance [to develop them],” he told Bioworld, a WeChat official account focusing on research. “The CRISPR-Cas13 systems are more specific and precise, so they have a broader scope of application.”

Chinese scientists find rice gene that can boost yield, shorten growth cycle

However, one obstacle that limits its clinical application is the enzyme’s collateral cleavage, or its ability to cleave nontarget RNAs.

“Due to this so-called collateral effect, Cas13 can degrade both target and non-target RNAs at random, thus making it difficult to design experiments and interpret results when using Cas13,” the researchers told the CAS website.

“The CRISPR-based gene editing tool does not permanently change the genome, and the effects of editing are controllable, reversible and safer.”

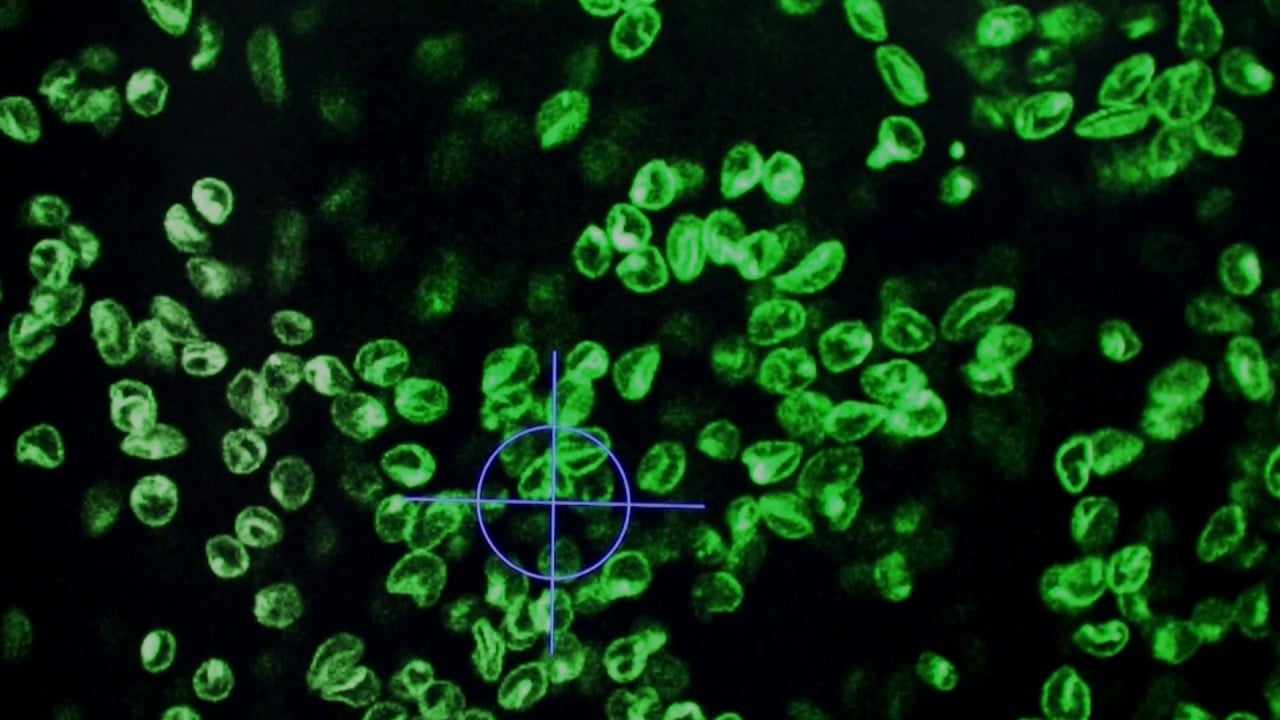

In a study published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Biotechnology last week, Yang and colleagues wrote that they had designed a system to detect the collateral effects of Cas13 in mammalian cells, and then used this to design a large number of variants.

One, named Cas13d-N2V8, showed a significant reduction in the number of off-target genes and no detectable collateral damage in cell lines and somatic cells, which indicated its future potential, the researchers said.

“In short, Cas13 variants with minimal collateral effect we developed are expected to be more competitive for in vivo RNA editing and future therapeutic applications,” the authors concluded in the study.

Scientist who made first gene-edited babies freed from jail in China

Previously, Zhang Feng, a gene-editing researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and one of the pioneers in the development of CRISPR, developed a platform called Rescue, which used Cas13 to edit RNA.

“By developing this new enzyme and combining it with the programmability and precision of CRISPR, we were able to fill a critical gap in the toolbox,” Zhang said in 2019.