What can the evolution of the turtle’s inner ear tell us about hunting ability – and agility?

- Analysis of 163 species finds the turtle’s proportionally big inner ear may have evolved to better stabilise its eyes for hunting in water

- Home to key phases of turtle evolution, China is ‘at the forefront of palaeontological headlines for turtles’ as it is for bird evolution, says author

Despite its famed slowness, the turtle has proportionally big inner ears which may have evolved to better stabilise its eyes for hunting in water, the researchers said.

They analysed 163 specimens, including extinct and living species such as softshell turtles, terrapins and loggerhead sea turtles and cite a Chinese fossil specimen as among the first to highlight the distinctive characteristic.

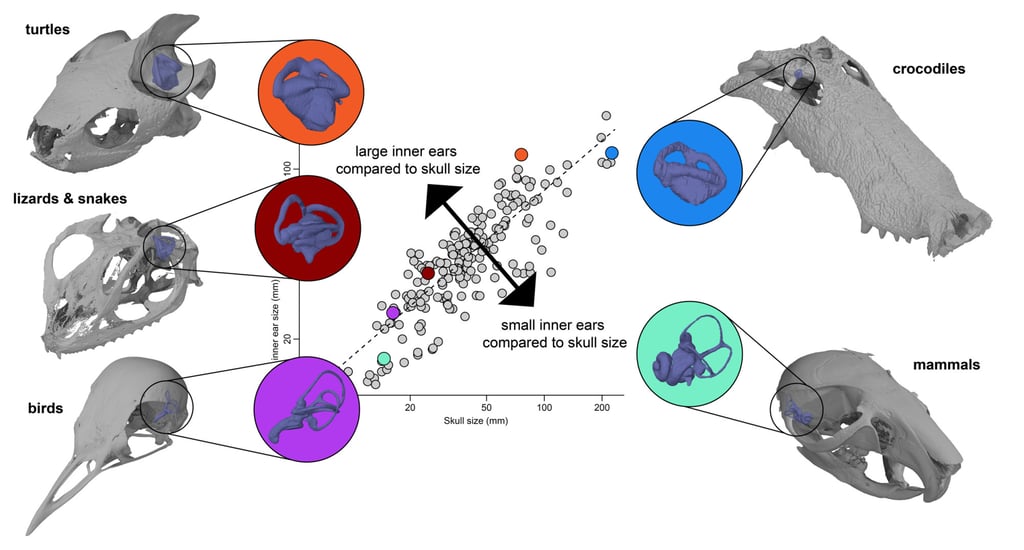

The inner ear, or bony labyrinth, is a tiny structure in the head that senses movement and orientation. The shape and size of the “organ of balance” had been used to infer agility in extinct animals.

But agility might not be the one-size-fits-all purpose for inner ear size across all groups of vertebrates, said lead author Serjoscha Evers, a research associate at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland.

“Turtles are quite slow, but nevertheless have inner ear sizes much larger than those of mammals and as large as those of birds. This indicates that there may be different explanations as to why large inner ear sizes evolve,” the palaeontologist said.

“We hypothesise that large inner ears in turtles facilitate better eye stabilisation, which could be a prerequisite for aquatic hunting behaviour, which first evolved in those turtles that also have large inner ears.”