Could this atomic-level breakthrough by Chinese scientists lead to cleaner emissions?

- A collaboration of researchers from China and the US says it has found a way to make reliable, efficient catalysts at atomic size

- Research could pave the way for faster and more reliable converters, which are used on everything from cars to fossil fuel power stations

All modern catalysts are molecular in size, with the efficiency of chemical production rising as the agent shrinks. Atomic-sized catalysts, with their unique electron structures, are 1-2 orders of magnitude more efficient, but their instability has been a problem.

Atomic catalysts often use precious metals such as platinum, rhodium and palladium, which tend to aggregate during reactions and lose momentum. Their shorter service life also means they are more expensive, making them unsuitable for commercial applications.

But the researchers say they have built a unique structure that solves these problems by confining the metal atoms to the surface of the supporting materials and preventing them from forming clusters. Their results were published in the October 26 edition of the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

The team, led by Zeng Jie, a professor with the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), included collaborators from Washington State University, Arizona State University and University of California, Davis.

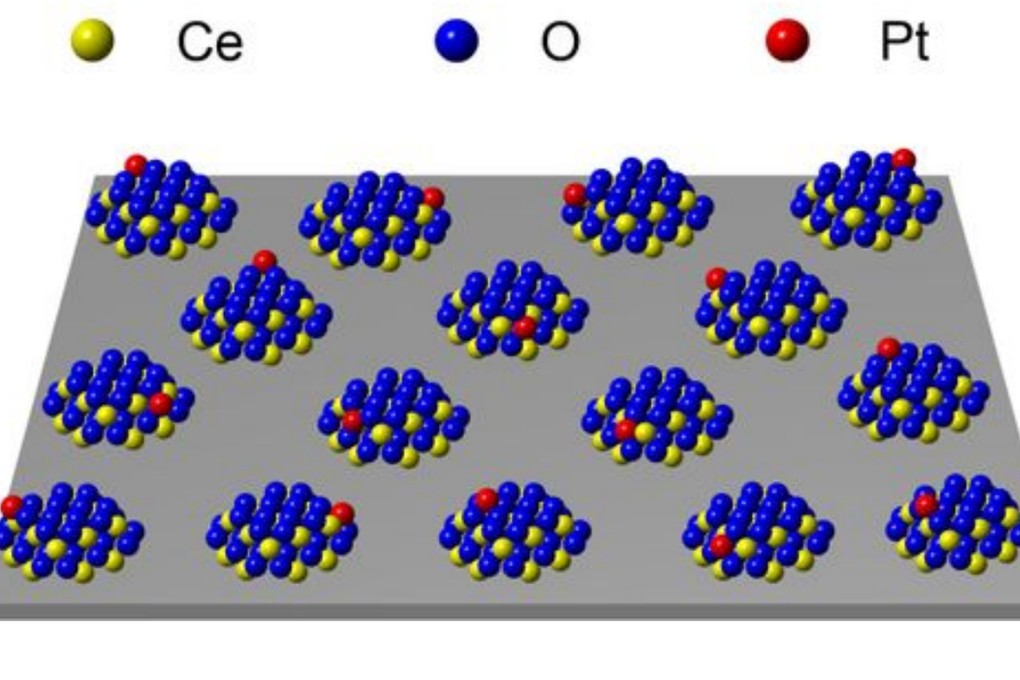

Using cerium oxide, the researchers built “nano islands” on the surface of silica particles, trapping the reactive metal atoms – in this case platinum – and holding them evenly through the chemical synthesis.

Effectively, the metal atoms are held in a series of island prisons, where they are free to move around but cannot escape, as the silica – no match for the bond between the metal and cerium oxide – acts like an impenetrable ocean.