Advertisement

Our distant past has revealed clues to that bad feeling in your gut

- Study led by researchers from China and Norway has uncovered evolutionary history of a notorious, widespread stomach bacteria

- H. pylori hitched rides with humans as they migrated from Africa, and now infects more than half the world’s population

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

New research has shed light on the mysterious past of a common bacteria that infects more than half the world’s population, and suggests how it became so pervasive.

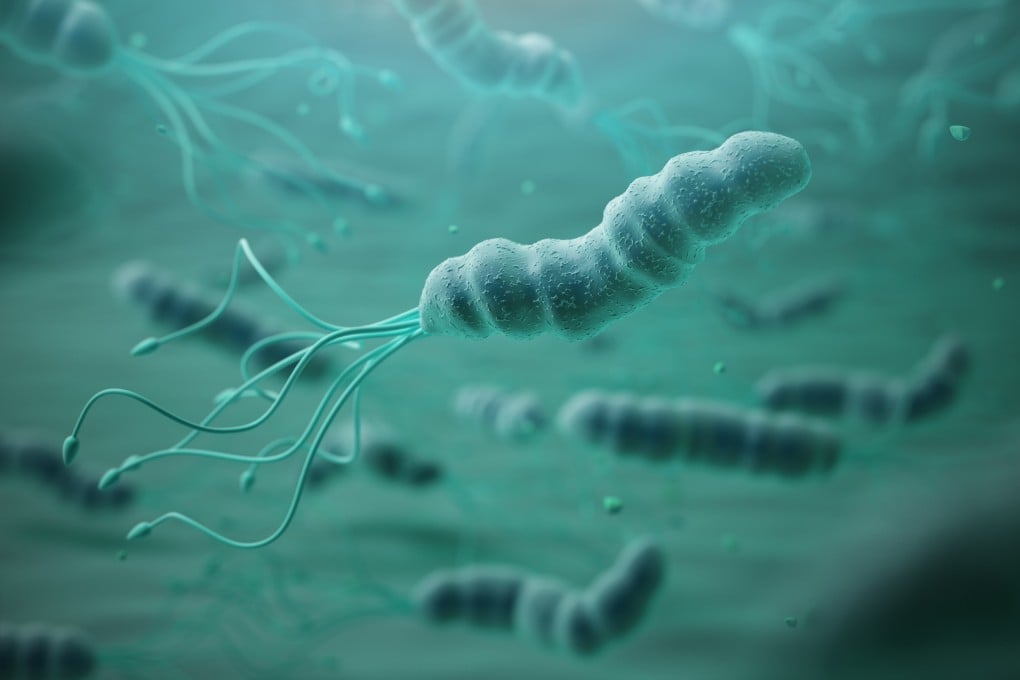

Helicobacter pylori, also known as H. pylori, is a very successful pathogen that makes its home in the human digestive tract and stomach. It is commonly found in people from Africa to Europe and in the Middle East. Once established, it can lead to chronic conditions like gastritis and stomach ulcers, and in some cases, stomach cancer.

In a study published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications on November 11, researchers revealed that the bacteria spread out of Africa in at least three waves as it followed ancient human migration patterns.

Advertisement

H. pylori has been living in human stomachs for more than 100,000 years, and predates the first human migration out of Africa by about 40,000 years. The bacteria’s genome – its set of genetic instructions – is considered a marker of human migration, since different strains of the bacteria can be associated with different geographic regions. But little else has been known about H. pylori’s origin.

Daniel Falush, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute Pasteur of Shanghai, who is also a corresponding author of the study, said genetic differences in H. pylori can now be correlated with human migration.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x