‘Dig into tough problems’: scientists remember Jiang Zemin for his intellectual curiosity

- Former president had a keen appreciation of science, ‘thirst to explore new ideas’

- Jiang sometimes even phoned researchers directly with tough questions

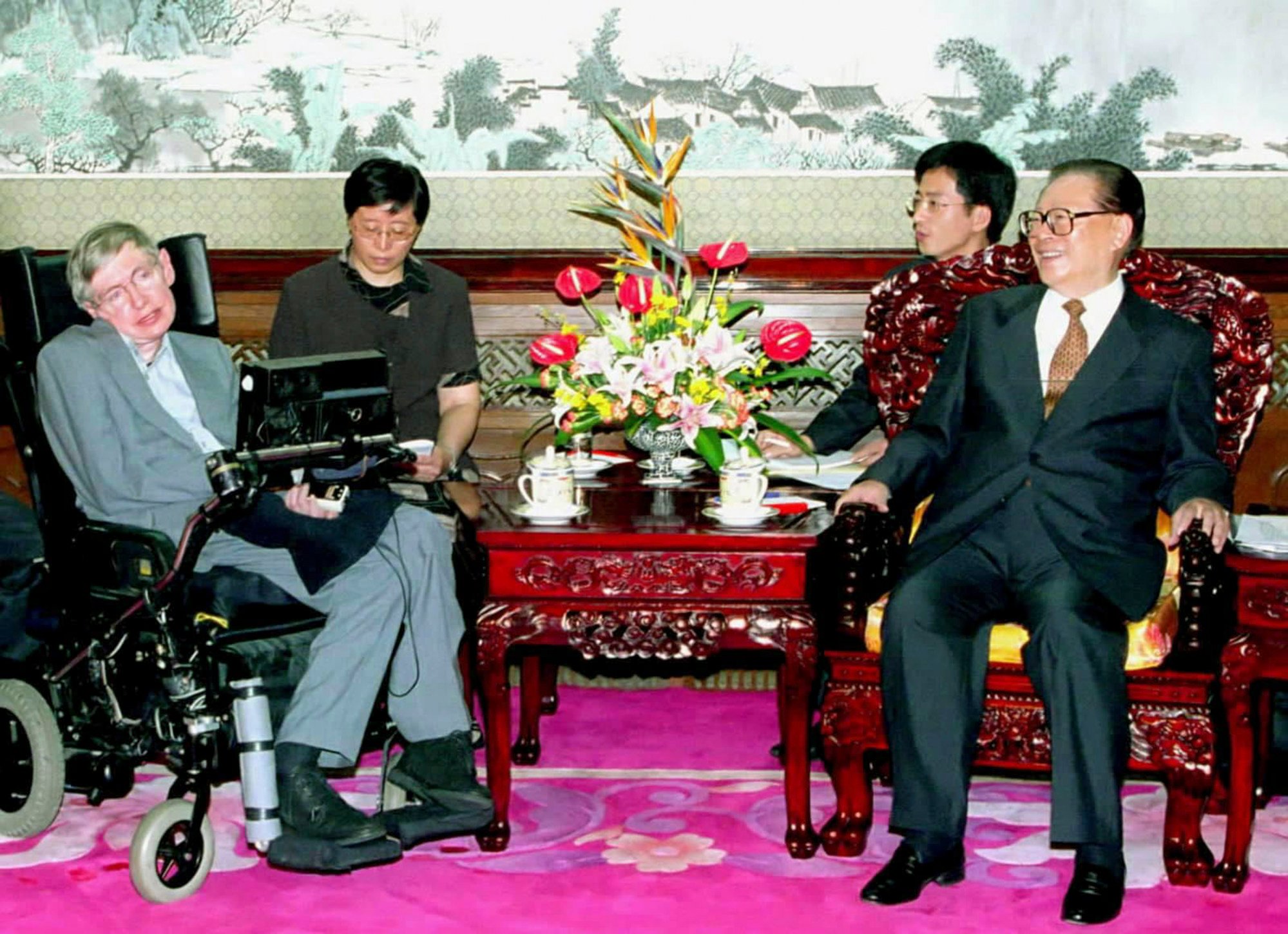

Former Chinese president Jiang Zemin has been remembered for his lifelong intellectual curiosity and keen appreciation of science. Jiang died last week at the age of 96.

‘Of great significance’: when Jiang Zemin met Bill Clinton and reset US ties

Rudolph Marcus, a professor of chemistry at the California Institute of Technology, met Jiang during a trip to China as part of a US Nobel laureates delegation in 2000.

“At a dinner in Beidaihe, we were asked to give advice to the government, so I spoke in favour of basic research – and not just applied research,” said Marcus, who received the 1992 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his theoretical work on electron transfer in chemical systems.

Marcus said he gave Jiang “examples of some striking consequences for society of what originally started as basic research projects”.

“And we both talked about our grandchildren … the meeting was delightful,” he said.

In Beijing in 2002, Jiang attended the opening ceremony of the International Congress of Mathematicians (ICM), a global gathering known as the “Olympics for Mathematicians”.

“The original plan was for the president to leave after conferring the Fields Medal to the winner,” recalled Ma Zhiming, a senior mathematician with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who was part of a team of local organisers for the congress.

But after Ma informed Jiang who would be speaking after the awards ceremony, Jiang decided to stay until the ceremony was over.

“Unlike what one might expect from a politician, he did not rush in to give a speech and rush out again. Rather, he sat and listened for 90 minutes,” according to the January 2003 issue of the Notices of the American Mathematical Society.

During the ICM opening ceremony, Jiang even got up from his seat to adjust a microphone for Shiing-Shen Chern, a distinguished Chinese-American mathematician who was sitting next to him.

“My foreign colleagues told me they were deeply touched by Jiang’s move, which would be unimaginable with leaders from their countries,” Ma said.

“Brother Jiang Zemin, the renowned classroom ‘doctor’,” one classmate wrote on Jiang’s graduation booklet from Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

“His grades are often among the top, and he’s especially good at math. He enjoys debates and often turns out to be the winner – because of all this, we grant him the ‘doctor’ title,” another wrote.

During his 1999 visit to Hou Kong Middle School in Macau, Jiang brought up a famous geometry problem known as Miquel’s Pentagram Theorem, which he failed to solve during his college entrance exam.

Singapore offers China condolences after death of ‘honoured friend’ Jiang Zemin

“I just wanted to use it as an example to show that we all need to keep an inquiring mind and dig into tough problems,” Jiang said to the students and teachers at the school. The complex theorem is now sometimes referred to as “Jiang Zemin’s problem”.

Jiang also had a passion for theoretical physics, according to the biography. In 1991, Chinese rocket pioneer Qian Xuesen received an unexpected call from Jiang, asking him for an explanation of superstring theory – an attempt to explain all the particles and fundamental forces of nature in one theory.

On another occasion, Jiang asked Song why the world existed in three dimensions. Song ended up visiting Jiang’s office, and the two discussed Riemannian geometry for an hour. “I always enjoy speaking with President Jiang. He has such a thirst to explore new ideas,” Song said.

“The Chinese people have every reason to be proud of their ancient tradition of civilisation,” Jiang said in 2000, during an interview with Science magazine. “But, on the other hand, we should not stop learning – not even for a single day – from all the fine traditions of the world.”