Why has China had such a struggle vaccinating the elderly against Covid-19?

- 23.8 million people over the age of 60 have yet to receive their first jab

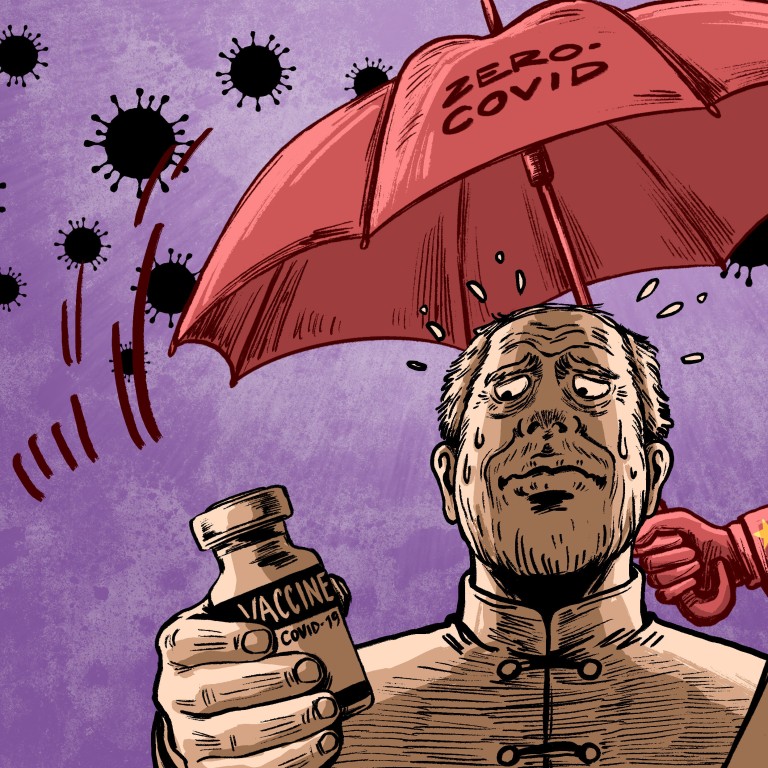

- Zero-Covid policy made vaccination seem less urgent for many people

He has had several operations to remove malignant bladder tumours since July last year and this summer, after finishing the first phase of chemotherapy, received conflicting advice about vaccination.

Two doctors from Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province, who first detected his cancer, advised him to wait and prepare instead for a second round of chemotherapy three months later. But two other doctors, from his hometown in Hunan province, said his condition was stable enough for him to get jabbed.

“If I get the shot, I’m worried about the spread of cancer cells; but if I don’t, I’m worried that if I’m infected it will harm my family,” Xiao said.

Xiao is one of the 23.8 million people over the age of 60 in China who have yet to receive their first shot of Covid-19 vaccine as the country abandons harsh pandemic restrictions and braces for waves of infection.

Over the past three years, many elderly people have been suspicious about the safety of vaccines, worried about their underlying diseases, and – largely shielded by the country’s former zero-Covid policy – unmotivated to get shots. With relatively low health literacy, some failed to get the support they needed to make such a decision from doctors, family and community workers or the government, many told the Post.

Second boosters drive for high-risk groups in China after zero-Covid shift

The elderly, most of whom have other ailments, are most concerned about the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines.

Xiao said he was confused by the different opinions from the doctors he consulted, and the lack of clarity about the standards they were based on, and he could not find other patients with similar conditions to ask their advice.

“I think the doctors don’t have enough hands-on clinical experience to tell me whether to get the shot or not, and they are very cautious,” he said.

Benjamin Cowling, head of the epidemiology and biostatistics division at the University of Hong Kong, said doctors’ different responses illustrated “the uncertainty about eligibility for vaccination on the mainland, where older adults with chronic conditions are not actually recommended to get vaccination”.

Claire Hooker, a senior lecturer in health and medical humanities at the University of Sydney, said it was “really important to acknowledge and respect people’s fears”.

“That means explicitly acknowledging that there will be many people who have a good reason to be worried – people who are older, people who have disabilities and who live with immunocompromised status for example,” she said.

In May last year, China recommended that five types of people not receive vaccinations, but that list has shrunk as it embarks on the road to reopening.

Wang Huaqing, chief immunisation expert at the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, said on December 13 that the only “absolute taboo” was a severe allergic reaction after vaccination, and advised those with chronic illnesses to get the jabs as long as their conditions were stable.

Are the new Omicron-focused boosters safe and effective?

As China promptly stamped out outbreaks while following its zero-Covid policy, vaccination seemed less urgent for many elderly people, especially those in the country’s vast hinterland, and they lacked the motivation to get jabs.

Huang Yuning, a 73-year-old who has rheumatism, got her second shot of vaccine on December 8 after thinking about it for a long time. Her daughter had kept dissuading her because she was worried her condition would deteriorate, even though Huang did not notice any side effects after getting her first jab in May.

Her hometown in Hunan had remained largely unscathed by outbreaks for almost three years – until recently.

“Since November, a couple of cases were reported and a building right opposite mine was locked down for two days,” Huang said. “I was scared and decided to get the second shot.”

A woman who looks after the needs of retired teachers at a university in Guangzhou said the elderly vaccination rate had risen as soon as local outbreaks began to increase in late October.

“After the relaxation, now there’s a little peak,” she said. “Many elderly are actively getting shots, thinking now it’s their own responsibility to protect themselves.”

One couple living at a nursing home in Zhongshan, Guangdong province – 75-year-old Li Yi and her 85-year-old husband – have not received any shots. Li has heart failure and her husband has Alzheimer’s disease, and both fear their conditions could worsen if anything goes amiss with the vaccines.

“My eldest sister, a doctor in Shenzhen, said she wouldn’t take the jabs and suggested we not do so, so I’d listen to her,” Li said.

She said medical staff at the nursing home had made no effort to encourage them to get vaccinated.

“They just keep a record to see if you want to be vaccinated or not,” Li said. “If you want to get vaccinated, you have to sign an informed consent paper. If you don’t, you should sign another form. It’s all up to you.”

Covid-19 vaccination in China is, in theory, voluntary, but when village cadres have carried out the drive in rural areas it has often featured an element of compulsion.

One nurse working in a small county in Hunan said her hospital set daily quotas for its vaccination campaign in May last year.

“The municipal health bureau ordered us to give 3,000 jabs a day at one point,” she said. “During that time, everyone in the village had to get vaccinated.”

She said people had to queue up, but some went away unvaccinated because vaccine supplies were occasionally insufficient.

Village cadres would visit the homes of elderly people and constantly phone those who had yet to be vaccinated, and even their family members, the nurse said. The village committee would send cars to transport bedridden elderly people to nearby clinics or dispatch vaccination teams to their homes to persuade them to get vaccinated immediately.

“It’s nearly done by force,” she added.

Huang Yuning said her younger brother, who lives in the countryside, had his third shot in July, after the village committee called his son numerous times to ensure compliance.

The nurse said, however, that while rural areas might have a higher first-shot vaccination rate because of the unwritten mandate, healthcare workers could find it harder to push people to accept a second or booster shot.

Some villagers complained of bad coughs, headaches and sore arms after being forced to accept their first shot, and after browsing alarmist posts about vaccine risks on social media platforms were more reluctant to get jabbed again.

Second boosters: what the studies tell us about the fourth Covid-19 jab

Meanwhile, she said, village vaccination missions were often deemed complete once a certain percentage of people had their first shot, which meant local cadres would no longer visit the elderly or take them to the hospitals.

She said one county resident in his 80s had died soon after vaccination in a village clinic and his family had sued for compensation, adding to vaccine hesitancy in the community.

“The old man had a heart problem and might have passed away even without the vaccine,” she said, while admitting it was difficult to make the general public understand “coincidental death”.

The vaccination roll-out in urban areas slowed this year when the zero-Covid policy was still being adhered to, as medical resources were focused on containing Omicron outbreaks across the country.

A community worker in Guangzhou told the Post: “If someone came he could get vaccinated, but that was not the priority in our publicity work. All the manpower was shifted to mass testing.”

Guangzhou resident Amy Luo said her 82-year-old father’s vaccination schedule had been disrupted by the sporadic outbreaks. He suffers from high blood pressure and arteriosclerosis, and received his first shot at a community centre in April.

When Luo planned to take him for a second dose last month, Guangzhou was mired in its biggest outbreak in three years, and the community centre suspended vaccinations and set up testing booths.

Luo waited anxiously as cases surged and finally took her father to get the second shot on December 6.

Three regional officials who attended recent policy briefings told the Post that Beijing aimed to ensure that more than 90 per cent of residents of the capital aged 80 and above received at least one dose of a Covid-19 vaccine by the end of January. On December 4, Beijing health authorities said 643,000 people over 80 had received their first shots – about 57 per cent of the age group.

Special task forces have been set up across China to oversee the vaccination of the elderly. Two members of task forces in Guangzhou said they had been collecting information about unvaccinated people over the age of 60 and had stepped up cooperation with community hospitals and clinics.

WHO says Covid-19 boosters needed, reversing previous position

“We have arranged door-to-door consultations with doctors to mitigate the elderly’s vaccine fears,” one of the officials said. “We’ve increased the number of fixed vaccination sites and inhaled vaccines, provided mobile vaccination vehicles … and carried out special vaccination sessions at night and weekends.”

On December 14, China rolled out a second-booster drive for high-risk groups including those aged 60 and over or with weak immune systems.