Scientists have come up with a new steel that is ultratough, yet stretchable

- They say a fingernail-sized piece can bear the weight of a 2-tonne car without fracturing, and it can also be extended by 18 to 25 per cent

- There is industry demand for such a material – both strong and ductile – for use in lightweight and safe transport, construction and infrastructure

A Chinese-led team of scientists say they have developed a new type of steel that is ultrastrong yet stretchable, potentially overcoming a tough challenge in steelmaking.

According to the team, a piece of the steel the size of a fingernail can bear the weight of a 2-tonne car without fracturing, and the ductile metal can also be stretched by 18 to 25 per cent.

They said the material would have applications in the vehicle, aerospace and machinery sectors, where it could be formed into complex shapes and absorb high energy from the impact of a collision.

The team – from Northeastern University in Shenyang, Shenyang National Laboratory for Materials Science and Jiangyin Xingcheng Special Steel Works in eastern China, as well as the Max Planck Institute for Iron Research in Germany – published their findings in the peer-reviewed journal Science on Friday.

Chinese team develops first ceramic material that can bend like metal

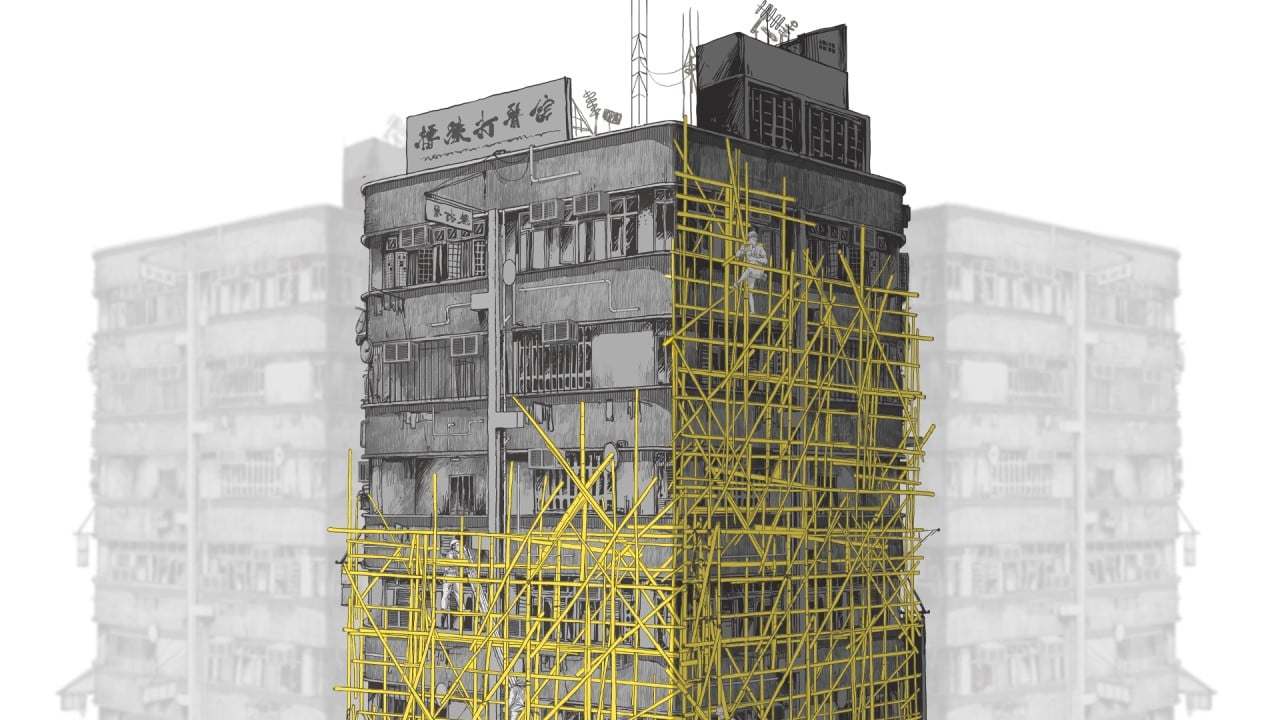

Creating ultratough steel that can also be extended has been a major challenge for scientists because strength and ductility are usually mutually exclusive. But there is industry demand for such a material for use in lightweight and safe transport, construction and infrastructure.

For the study, the researchers came up with a new hierarchical nanostructure design, aiming to produce a steel with both characteristics.

To create it, they forge melted raw alloyed material at 650 to 800 degrees Celsius (1,200 to 1,470 Fahrenheit) and let it air cool, during which the special structure formed. They then used liquid nitrogen – which has a temperature of minus 196 degrees Celsius – to cool it down further, before heat treating it at 300 degrees Celsius to improve its stability.

Lead author Li Yunjie, a postdoctoral researcher at Northeastern University’s State Key Laboratory of Rolling and Automation, said it was a much simpler process than that used to make conventional ultrahigh-strength steels, which are rolled to form thin plates or sheets.

He said it produced 2 gigapascal-strength steel, which was “almost the highest tensile strength in steels”.

In addition, Li said the manufacturing method could reduce the cost of producing a tonne of steel by about 510 yuan (US$75) and cut carbon emissions by more than 100kg coal equivalent per tonne.

“[It] contributes to enormous economic benefits and promotes green development,” he said.

According to Li, the future of producing the steel at a tonnage scale is promising.

“The associated processes proposed in our study – especially the forging procedures – have long been widely used in many companies and production environments to produce parts like axes, ship shafts and so on.

“There is already large-scale ship shaft with a tonnage scale based on the forging,” he said. “Our process is consistent with its preparation with only a few adjustments in some process parameters.”

Asia’s steel industry will take decades to go green, says mining giant BHP

He said industrial heat treatment platforms could be used to treat the forged products, followed by cooling and tempering using large-scale deep cold boxes and furnaces.

The team is now working on practical use of the steel by looking into specific application scenarios and evaluating its performance in other areas such as metal fatigue and fracture toughness.

Engineering professor Geoffrey Brooks – who researches steelmaking at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia and was not involved in the study – said the new material was attractive for transport applications.

“The high strength effectively means that you don’t need as much steel, thus reducing weight and the greenhouse emissions associated with moving vehicles,” Brooks said.