‘Irreparable mess’: China and France dissolve 19-year scientific partnership in Shanghai

- Institut Pasteur of Shanghai renamed the Shanghai Institute of Immunology and Infection as scientific collaboration ends

- Students and researchers in the dark about what the demise of the partnership will mean for the future

On July 26, outside a walled compound on Yueyang Road in Shanghai, a stone plaque inscribed “Institut Pasteur of Shanghai” was quietly replaced with a new one reading, “Shanghai Institute of Immunology and Infection”. On the same day, the website was also renamed and updated.

The French scientific research centre first partnered with CAS back in 2004. But in March this year, it announced the termination of that alliance, saying: “The Institut Pasteur decided in December 2022 to suspend its partnership agreement with the Chinese Academy of Sciences regarding the Institut Pasteur of Shanghai.” At the time, it indicated the name of the organisation would also change as a result.

It is possible that the writing was on the wall. Since 2021, the Institut Pasteur of Shanghai (IPS) has not been an active member of the Pasteur Network, made up of 33 institutions from 25 countries and regions.

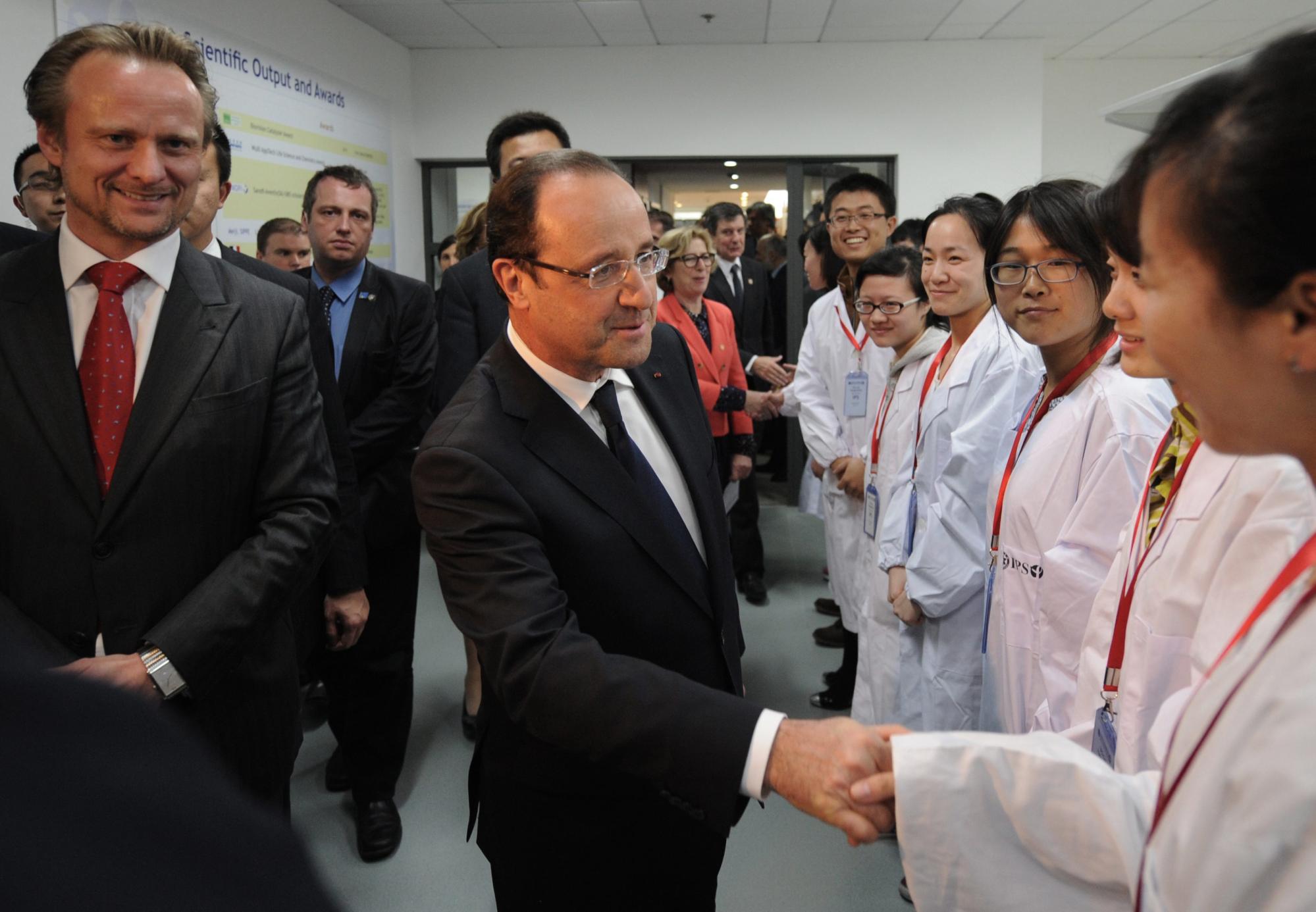

The year 2018 marked the 40th anniversary of the China-France governmental agreement on scientific and technological cooperation. As part of that cooperation, the IPS served as an emblem of scientific diplomacy between the two nations.

Humanity loses when nations are at loggerheads

Now, with China betting big and pouring resources into its science sector, the situation at IPS should serve as a hard-learned lesson to try to avoid such problems, according to some scientists.

One IPS doctoral student who has recently graduated told the Post the Institut Pasteur’s decision was “completely reasonable and understandable” given that the IPS had strayed away from its original research mission.

When the IPS was established 19 years ago, it was just after the outbreak of Sars, or severe acute respiratory syndrome. Leveraging the expertise and international influence of the Institut Pasteur, the organisation was expected to boost China’s scientific power in emerging infectious diseases.

Despite being one of the smallest institutes within CAS, over the years, the IPS has become a leader in the fields of virology, vaccine development and immunology, among others. It has made substantial contributions in these areas and has boasted many influential researchers for China. IPS scientists have studied viruses including hepatitis C, Ebola, HIV and Zika, as well as developing drugs and vaccines.

However, when the 21st century’s most significant public health crisis struck – the Covid-19 pandemic – it did not find itself in the spotlight.

For scientists familiar with the institute, the ending of the partnership comes as no surprise. In fact, by the end of last year, rumours suggested it was a near certainty.

“Every five years, CAS and Institut Pasteur would review and assess their cooperation. The last evaluation of IPS, which was conducted at the end of 2021, showed that Institut Pasteur was very dissatisfied with the leadership of then-director Tang Hong. By mid-2022, rumours had already surfaced that it could no longer collaborate with CAS and it became almost certain by the end of 2022,” said one insider, who asked not to be named.

According to a news report, Institut Pasteur deputy director François Romaneix referred to dissent in “management rules” among the partners of the IPS.

The IPS was co-led by two directors, nominated by Institut Pasteur and CAS. However, its Chinese director, Tang, whose tenure ran from 2015-2022, was removed from his position on April 1, 2022.

The renamed institute has not officially announced its new director yet.

Multiple scientists who had worked at the IPS until recently told the Post that although some friction did exist regarding leadership over the past decade, conflicts intensified rapidly after the appointment of Tang. They described the situation at IPS as an “irreparable mess” and severing its ties with CAS became the only option for Institut Pasteur.

At least 10 principal investigators and more research personnel, some who are French, such as monkeypox virus expert Nicolas Berthet, have resigned in the last five years. Also, among the 28 principal investigators employed at the IPS, 16 were recruited within the last five years.

According to the 2017 IPS annual report, that year the institute had 16 scholars belonging to the “Hundred Talents Programme” of CAS. Now, most of them are scattered to various labs and universities. For instance, virologist Lan Ke joined Wuhan University in 2017 and is serving as the director of the China State Key Laboratory of Virology.

The loss of talent had a noticeable impact. In 2016, the IPS published 10 articles in the Journal of Virology, ranking first nationwide. However, in 2019 and 2021, it only had one paper published in the journal, placing it well outside the top 20 rankings.

A scientist who worked at IPS for nearly a decade said in recent years, thanks to economic development, China had been attracting scientists from overseas, and infectious disease-related research had gained substantial improvements. The regressive development of the IPS sits in sharp contrast to this.

It is also a long way from how the scientific collaboration first began.

At the end of 2003, Chen Zhu, then vice-president of CAS, who had studied in France, emphasised the need to strengthen China’s scientific cooperation with developed countries. After that, strategic partnerships with renowned research institutions like Germany’s Max Planck Society, France’s CNRS, Japan’s RIKEN, and Russia’s Academy of Sciences were announced.

At that time, the Sars outbreak highlighted the fact that China lagged in microbiology and virus research. By contrast, France was home to the world’s pre-eminent research institution in this area: Institut Pasteur, which has 10 Nobel laureates to its name.

A joint statement signed by the Chinese and French governments in January 2004 listed combating emerging diseases as a priority for the partnership between the two countries.

To nurture innovation, the most vital thing is to create a vibrant and free environment for scientists. Researchers do not want to be over-regulated

From 2004 to 2009, the first director of the IPS was renowned French virologist Vincent Deubel, who had previously served as the head of the P4 laboratory in Lyon, France, making it the first institution on the Chinese mainland headed by a foreign scientist.

In May 2008, the French petroleum group Total signed a three-year scientific cooperation project in Shanghai with the Institut Pasteur, providing the IPS with 5 million yuan (US$700,000) in support of the research on viral hepatitis prevention in China.

The resources and reputation of the institute in turn attracted influential scientists.

One, who gave up a position in a prestigious laboratory in the United States to join the IPS soon after its formation, said at that time the scientists were given autonomy to apply for funding and conduct research. He resigned from the institute in 2020.

Yize Li, now an assistant professor at Arizona State University in the US, studied at the IPS from 2005 to 2012. He said that, at that time, it was operated like a typical Western lab and scholars had access to rich academic resources within the network of Institut Pasteur.

In 2015, the IPS’ “Director’s Message” proudly highlighted its structure: among its 25 research groups, three major areas – pathogen, immunology and vaccine development – were strategically laid out. Meanwhile, the institute had secured research projects from the National Institutes of Health in the United States, showcasing its strong competitiveness on the global stage.

Former IPS employees agreed that 2016 marked a turning point.

Three scientists interviewed by the Post all described Tang’s administrative culture as authoritative and strict, as they were given less say in hiring research assistants, applying for funding and choosing research projects.

Meanwhile, financial challenges increased after 2017 when fixed funding for principal investigators was reduced by about half, and it was further exacerbated because the increased proportion of administrative staff ate into operating budgets.

However, another scientist told the Post the reason he resigned had less to do with money; it was the significant shift in the institute’s development direction that confirmed his decision.

“In recent years, there doesn’t seem to be a clear layout when recruiting researchers,” he said.

As experienced principal investigators leave, consequently the IPS loses its strength.

Unsafe, unwelcome: US-based scientists feel ‘chilling effects’ of China Initiative

Taking the vaccine development area as an example, the IPS recruited four principal investigators between 2005 and 2012, specialising in different vaccine technology approaches. They were regarded as an influential team in the CAS system. Now, of the four, three have resigned and the other has retired.

In 2019, IPS established the Centre for Microbes, Development and Health, focusing on studying gut microbiota. French microbiologist Philippe Sansonetti was appointed as the director. This centre was regarded as Tang’s new focus, which he had unevenly allocated resources to. However, the centre has not generated significant results and Sansonetti is seldom present, according to scientists interviewed by the Post. The centre’s website page cannot be found on the updated IPS website.

An anonymous letter online criticised the institute, saying that due to improper allocation of funds and an excessively centralised leadership style, Tang, during his tenure as director, has driven the institution “into the abyss”. When the Post contacted Tang to ask for clarification, he declined to comment.

Now, as “Institut Pasteur of Shanghai” no longer exists, the impact it may have on current researchers and students is unknown.

Several incumbent researchers who were contacted declined interview requests and one French scholar expressed concerns that negative publicity for the institution may make the situation deteriorate.

Yize Li said he believed that, with the collapse of the collaboration, the organisation left in its place would no longer enjoy the prestige of the Institute Pasteur, which in turn might affect students’ future academic pursuits and job hunting. Cutting ties also means losing valuable opportunities for training and learning in other Pasteur branches.

However, over the years, China has progressed significantly in the infectious diseases field. Alice Hughes, a conservation biologist at the University of Hong Kong, who collaborates with researchers at the Shanghai institute, said China was now an established scientific powerhouse, so CAS might not see as much value in co-leading such an institution with a foreign organisation.

“To nurture innovation, the most vital thing is to create a vibrant and free environment for scientists. Researchers do not want to be over-regulated,” one scientist, who worked for the IPS for years, said. He added that academic institutions would thrive only when they were given freedom and discretion.

In its official statement, Institut Pasteur said: “This choice was made in order to begin a new cycle of conversations for improving the relationship between the two organisations and finding a more productive way to work together.”

The Post contacted the Institut Pasteur for clarification about those ways, but no specific response was provided.

Meanwhile, students and researchers remain in the dark. On July 26, a doctoral student who graduated from IPS in 2022 reposted a photo of the new stone plaque that read, “Shanghai Institute of Immunology and Infection”, and asked: “In the future, how will I introduce my educational background?”