Deaf children enter a world of sound as gene therapy clinical trial shows ‘life-changing’ results

- A Chinese-led clinical trial for a gene therapy to cure congenital deafness has restored the hearing of five out of six test patients

- The treatment is delivered via a single injection and uses a genetically edited virus as its delivery vector

A clinical trial of a new gene therapy has delivered startling results for children born with hearing loss.

Between October 19, 2022 and June 9, 2023, 425 participants were screened and six children were eventually enrolled in the trial. They had all been diagnosed with autosomal recessive deafness 9, which is caused by mutations in a gene called otoferlin, or OTOF. This had led to the patients’ severe to complete bilateral hearing loss.

Six months after the gene therapy, five of the children showed significantly improved hearing.

Shu Yilai, lead scientist of the study, said in an interview with the Chinese new media platform Bioworld that the children’s hearing had “reached a level similar to that of 60-65 per cent” of the general population.

“On average, they went from being unable to hear below 95 decibels – similar to the sound of a motorbike – to being able to hear around 45 decibels, which is close to a normal speaking voice,” said Shu, who is a professor at Fudan University’s Eye and ENT Hospital.

Worldwide, 26 million people are living with congenital deafness. In China, around 30,000 babies are born every year with hearing impairment or loss, 60 per cent of which is due to genetic disorders. This can severely affect their language, speech and cognitive development.

The therapy involves a vector transporting the DNA of the correct version of the OTOF gene directly to hair cells in the inner ear, enabling them to express functionally normal proteins that fundamentally restore or improve hearing in deaf patients.

Could this be the cure for ALS, Parkinson’s and more? Early test bodes well

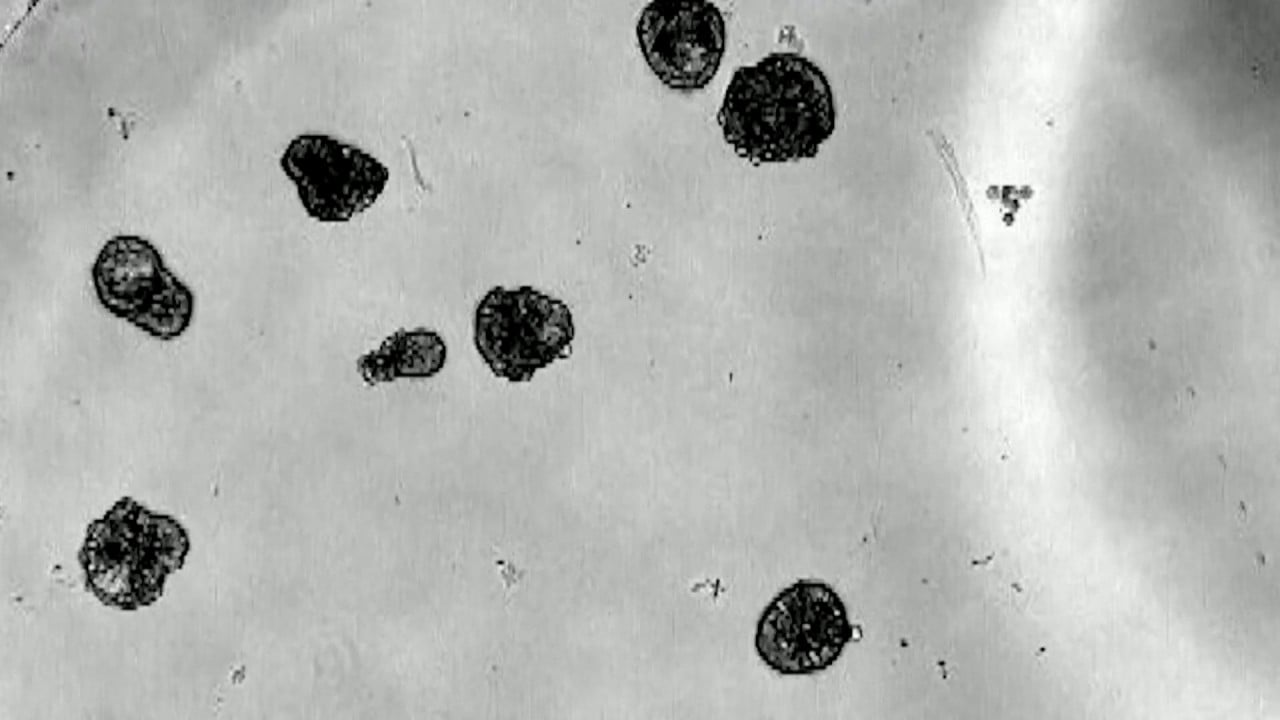

The delivery vehicle used in this study was the adeno-associated virus (AAV) – the most commonly used vector in gene therapy – which is transformed from a naturally occurring virus into a delivery mechanism by replacing the viral DNA with newly encoded DNA.

“AAV-based gene therapy is particularly suitable for treating diseases caused by a single gene defect,” Cui said.

In this case, congenital deafness is well understood, so a cure could theoretically be achieved by delivering the correctly encoded gene into cells.

There were two potential explanations for why some patients did not respond well in the trial, according to Shu. It is possible the patient had previously been infected with the AAV, which triggered an immune response against the virus. When the patient encountered the AAV-loaded drug again, the patient’s immune system’s antibodies would have attacked it as a foreign enemy.

Shu said the other possible reason is the therapy might not have effectively reached the child’s inner ear hair cells.

In terms of safety, there were no dose-limiting toxicities or serious adverse events observed in any of the six children treated. Of the total 48 adverse events recorded, 46 were grade 1-2, indicating that the severity was relatively low.

‘One-time treatment, lifetime cure’: Chinese firm behind thalassaemia therapy

Cui, the Novartis Gene Therapies scientist, said another important outcome of the study was that it clinically demonstrated the feasibility of dual AAV as a delivery system, which would broaden the prospects for application of the technology.

But AAV is a very small virus.

“The relatively small gene fragment it can piggyback on, about 4,700 base pairs – the basic building blocks of genes – limits its application,” Cui said.

But the team overcame this problem by using two AAV vectors to deliver the OTOF gene. Although the idea had been proposed for years, this study showed that it worked in practice, Cui noted.

Gene therapy is a hot area in both scientific research and pharmaceutical communities – and therapies based on the AAV viral vector system have led to a number of revolutionary drugs in recent years.

Various potential therapies derived from this technology “have attracted a lot of investment and accelerated into clinical trials,” Cui said. To date, seven AAV gene therapies have been approved and marketed worldwide.

Chinese scientists find glimmer of hope for blind in gene-editing study

On January 23, Akouos, a subsidiary of pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly, announced that the first participant in a clinical trial had regained his hearing within 30 days of receiving its gene therapy – which works on the same principle as Fudan University’s – after suffering severe hearing loss for more than a decade.

But Cui also warned that gene therapy research is still at a relatively early stage. For one thing, when a disease involves a genetic mutation that is spread throughout the body, a very high dose is needed to achieve efficacy. This can raise safety concerns, and there have even been cases of death.