Scientists find a way to make oxidation a good thing for metal, on a tiny scale

- Research team developed an oxidised nanomaterial that they say is superelastic

- It could be used to kill bacteria and viruses, protect relics, or for medical devices

It is well known that some metals can oxidise, corrode and form rust when exposed to air, degrading the material. But scientists have found that oxidation could actually be beneficial for metals – at the nanometre scale.

The team in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan developed an oxidised nanomaterial they say is superelastic.

That means the metal can recover from deformation, and according to the researchers it could be used to kill bacteria and viruses, to protect relics, or even for wearable medical devices.

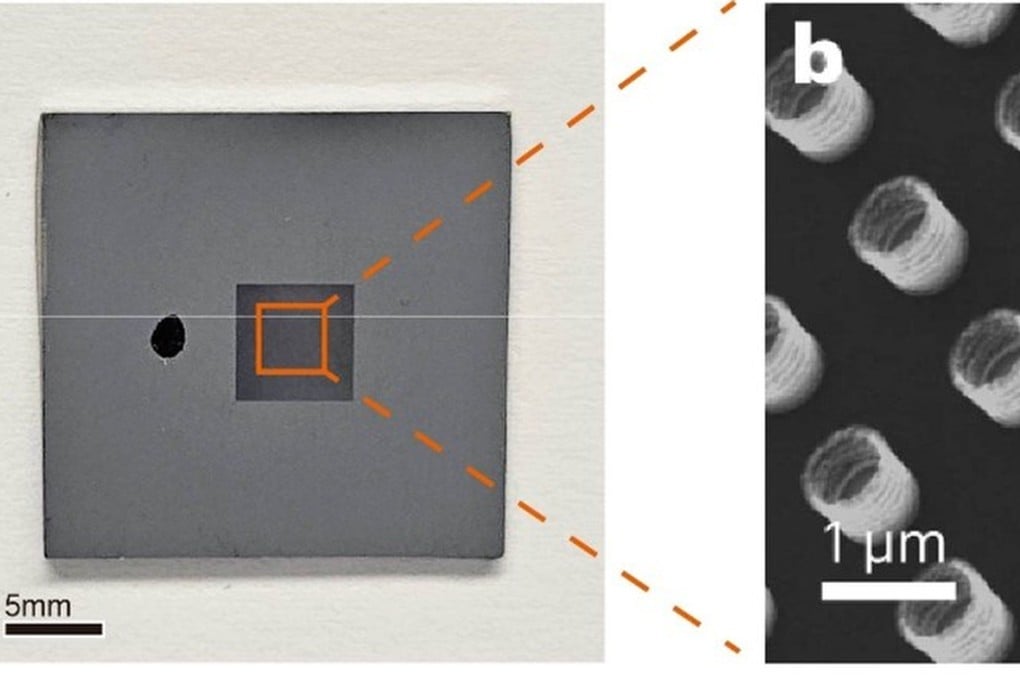

“We experimentally demonstrate that metallic glass nanotubes are superelastic at room temperature, which outperform various superelastic metals and alloys known to date,” they wrote in a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Materials in December.

“This unique property of the metallic glass nanostructures is useful, which could find many applications in future nanodevices working in harsh environments, such as sensors, medical devices, micro- or nanorobots, springs and actuators.”

The study – a years-long collaboration – was carried out by a team from City University of Hong Kong, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing Computational Science Research Centre, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, and Shenzhen University.

Many metals react with oxygen, with silver, platinum and gold being some of the exceptions. For example, iron oxide, commonly known as rust, is produced when iron comes into contact with oxygen and water. So keeping storage areas dry is one way to prevent iron or steel tools from rusting.

Lead author Yang Yong, a professor with CityU’s mechanical engineering department, said the team’s discovery goes against the conventional belief that oxidation only harms metal.