Roses are red, violets are blue; does AI poetry do it for you?

China’s literary circle divided over value of poems created by artificial intelligence

Would you enjoy reading poetry created by a machine? That’s the question that has divided China’s literary circle, since Microsoft’s artificial intelligence chatbot published a book of Chinese poems.

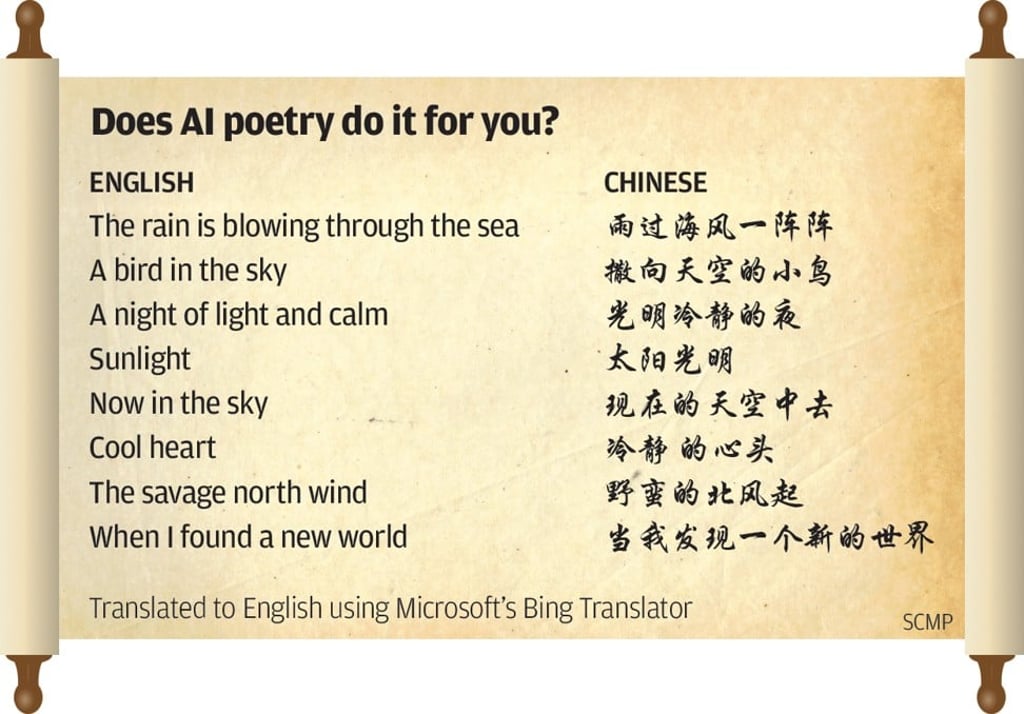

The rain is blowing through the sea/ A bird in the sky/ A night of light and calm/ Sunlight/ Now in the sky/ Cool heart/ The savage north wind/ When I found a new world.

That’s the English translation of one of the 139 poems penned by Xiaoice in its book, The Sunlight That Lost The Glass Window.

The book, published on May 19 by Beijing-based Cheers Publishing, is said to be the first-ever poetry collection written by AI.

While some Chinese poets have embraced Xiaoice’s works, hoping the new technology helps revive appreciation of the art form among the younger generation, others have expressed doubt about the quality of the poems.

In critiquing Xiaoice’s poem above, literature professor Zhang Zonggang said the machine’s work had indeed created a “new world” that could evoke feelings in human readers that are different from those aroused by reading a normal piece of poetry.