China calls off controversial hunt for Chinese ‘warrior gene’ in children

Poor results rather than ethical issues stopped studies focused on blood samples from violent juveniles, source says

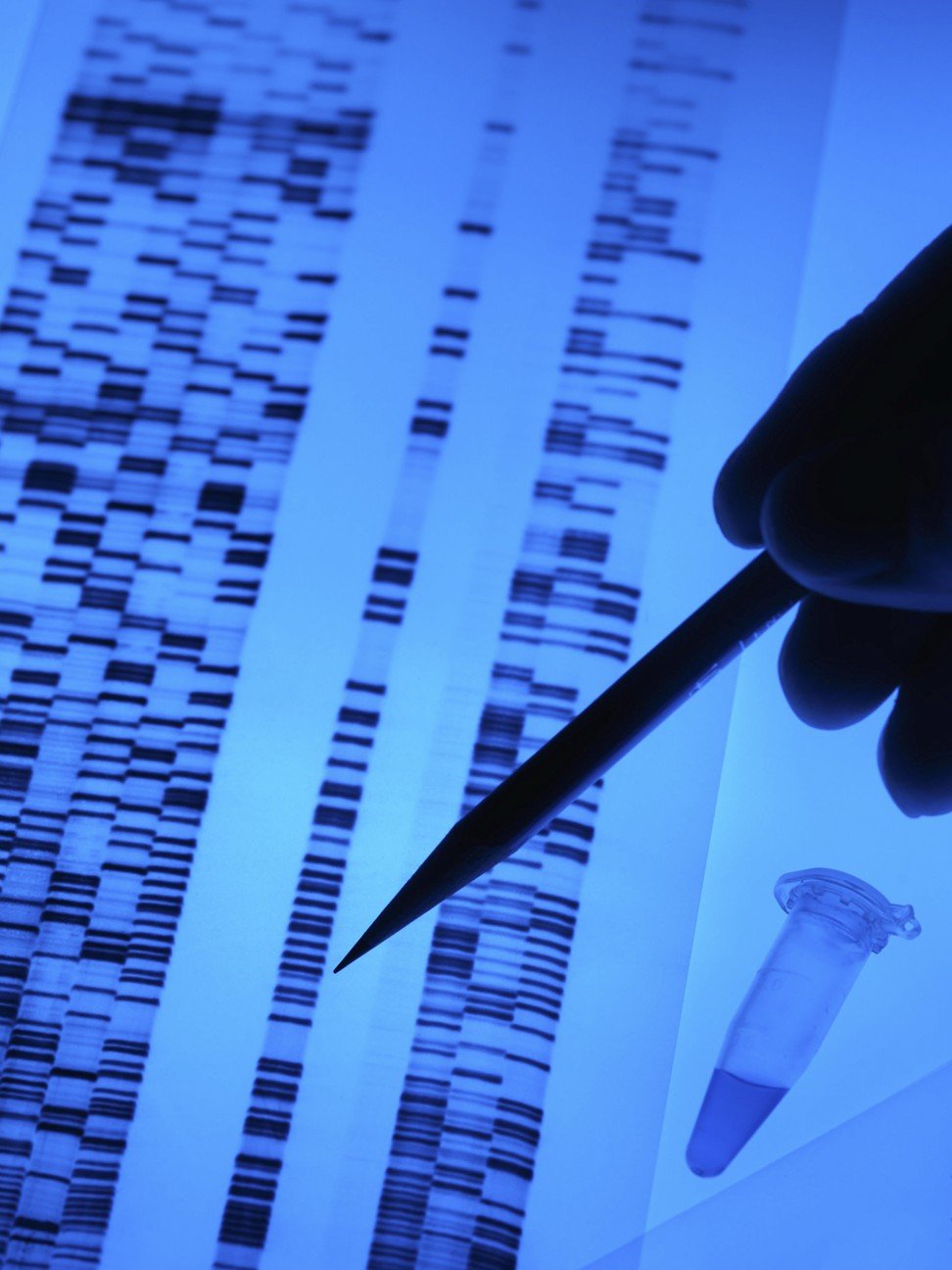

The hunt started more than a decade ago with a pool of money, central government backing and the goal of tracking down a Chinese variant of the so-called warrior gene.

Similar research was already under way in the United States, Europe and Japan – studies that suggested certain variations in DNA were linked to violent behaviour.

Identifying those traits might not only help reduce the risk of such violence but also be a way of boosting aggression and building a better soldier, the thinking went.

But after sifting through blood samples from hundreds of children convicted of violent crimes, researchers came up empty-handed, prompting the authorities to stop the funding and abandon the controversial quest, sources said.

The Chinese research focused on DNA from inmates at juvenile detention centres across the country.

From 2005, samples were taken from minors convicted of crimes ranging from robbery to assault and murder, some committed before the inmates were 14.

Minors were chosen because they were less exposed to social factors than adults, leaving more scope for genetics to play a role.

In some cases the samples were taken with the consent of the child’s legal guardian but in others the juveniles were told to roll up their sleeves and submit, researchers involved in the programme said.

The samples were compared to those from non-violent inmates as well as “ordinary” children of a similar age.

The programme attracted criticism from the start, with some researchers in China as well as the United States and Europe flagging fears that such studies could lead to the genetic labelling of a person at birth. That information could then be used to suppress or exploit people with aggressive traits, they said.

But after millions of yuan and years of effort, the programme was quietly declared a failure.

Meng Huaqing, director of psychiatry at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University and a lead scientist in the programme, said the government had gradually cut financial support to nearly all related research in the last couple of years.

“It is almost impossible to get money nowadays. The programme is dead,” said Meng, who has also sat on the funding review panels of the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Ministry of Science and Technology.

Meng said the programme was not killed by ethical issues, which “did not exist in practice”, but universal reports of negative results.

The researchers found that genes played an almost negligible role in aggressive behaviour compared to environmental factors such as poor social support, physical abuse and instability at home.

Analysis by the Central South University in Changsha, Hunan province, on candidate “warrior genes” in nearly 400 juvenile inmates in Hunan, Sichuan and Guangdong provinces found no statistically significant relation between violent act and genes, according to a document obtained by the South China Morning Post. Researchers found that outbursts of youth violence were more strongly correlated with smoking, drinking and school punishment.

Meng said other teams reported similar results.

“Genetics are only one driving force. A change of environment can lead to a change in human behaviour,” he said.

Zhang Xiaohui, neurologist and principal investigator at the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning at Beijing Normal University, said he was not surprised that the government was giving up the research on specific warrior genes.

Zhang said the human brain was very plastic and life experience could significantly change the “wiring” of neurons, affecting personality and behaviour.

“The shaping of behaviour by DNA and life after birth life is about 50-50. Genes also tend to work in a group, and to determine a group of warrior genes we need to find a stable pattern passed down from several generations,” he said.