Son of German artist and Holocaust survivor says thank you to Shanghai with his father’s work

A collection of 32 pieces by David Bloch has gone on permanent display at the Jewish Refugees Museum in city the artist called home for nine years

It was a stroke of incredible luck that allowed David Bloch, an artist and German Jew, to obtain his release from Dachau, a Nazi concentration camp, during the second world war. But his fortunes improved still further when his subsequent escape from Germany took him to Shanghai.

In 1940, the year of Bloch’s arrival, Shanghai was the only city in the world opening its doors to Jews without requiring a visa. More than 20,000 of them travelled to the eastern China city seeking freedom from Nazi persecution.

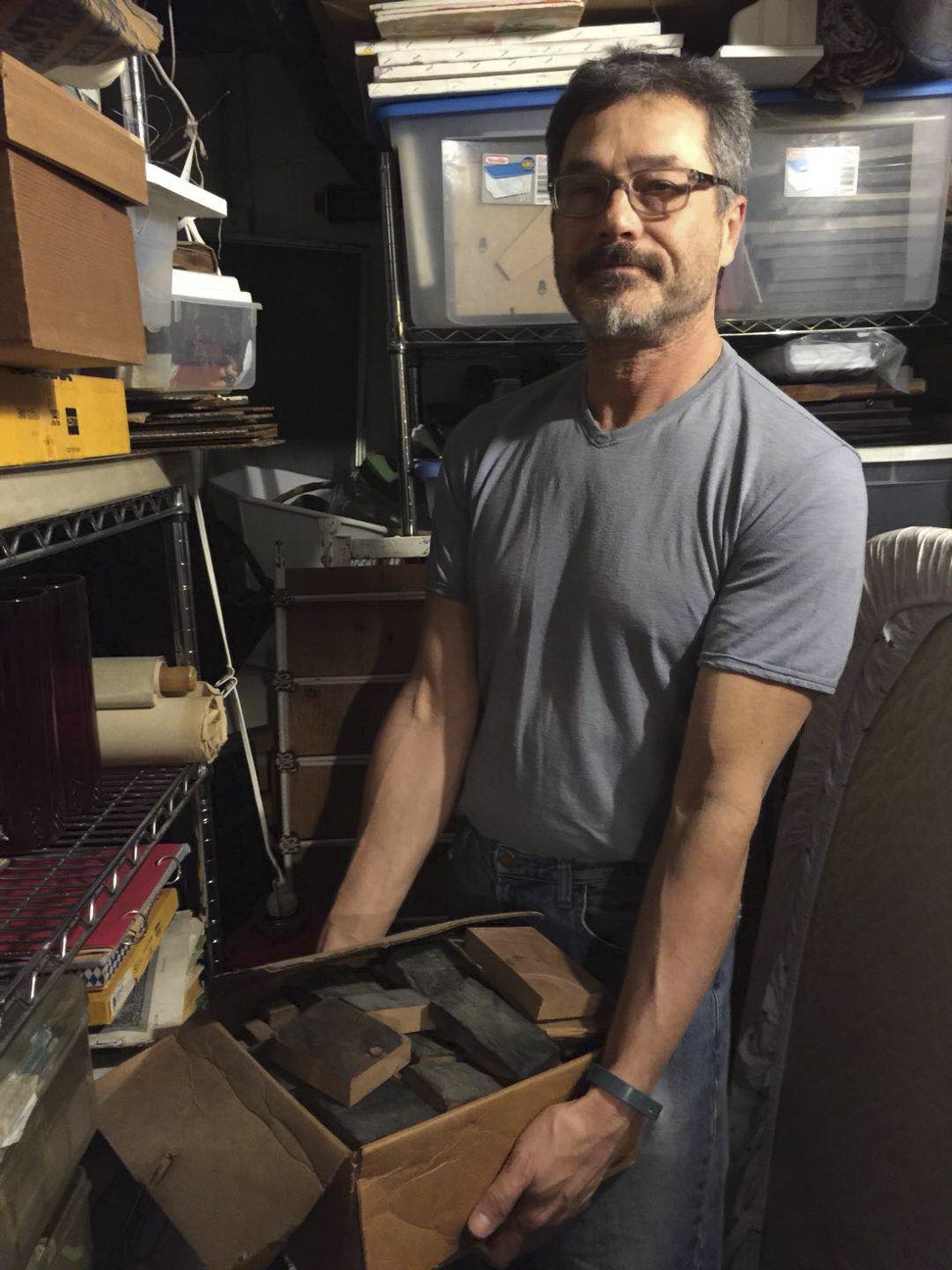

On Friday, Dean Bloch, the son of David Bloch and Zheng Dixiu, handed over 32 pieces of his father’s work, as well as the tools he used to make them, to the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum, where they will remain on permanent display.

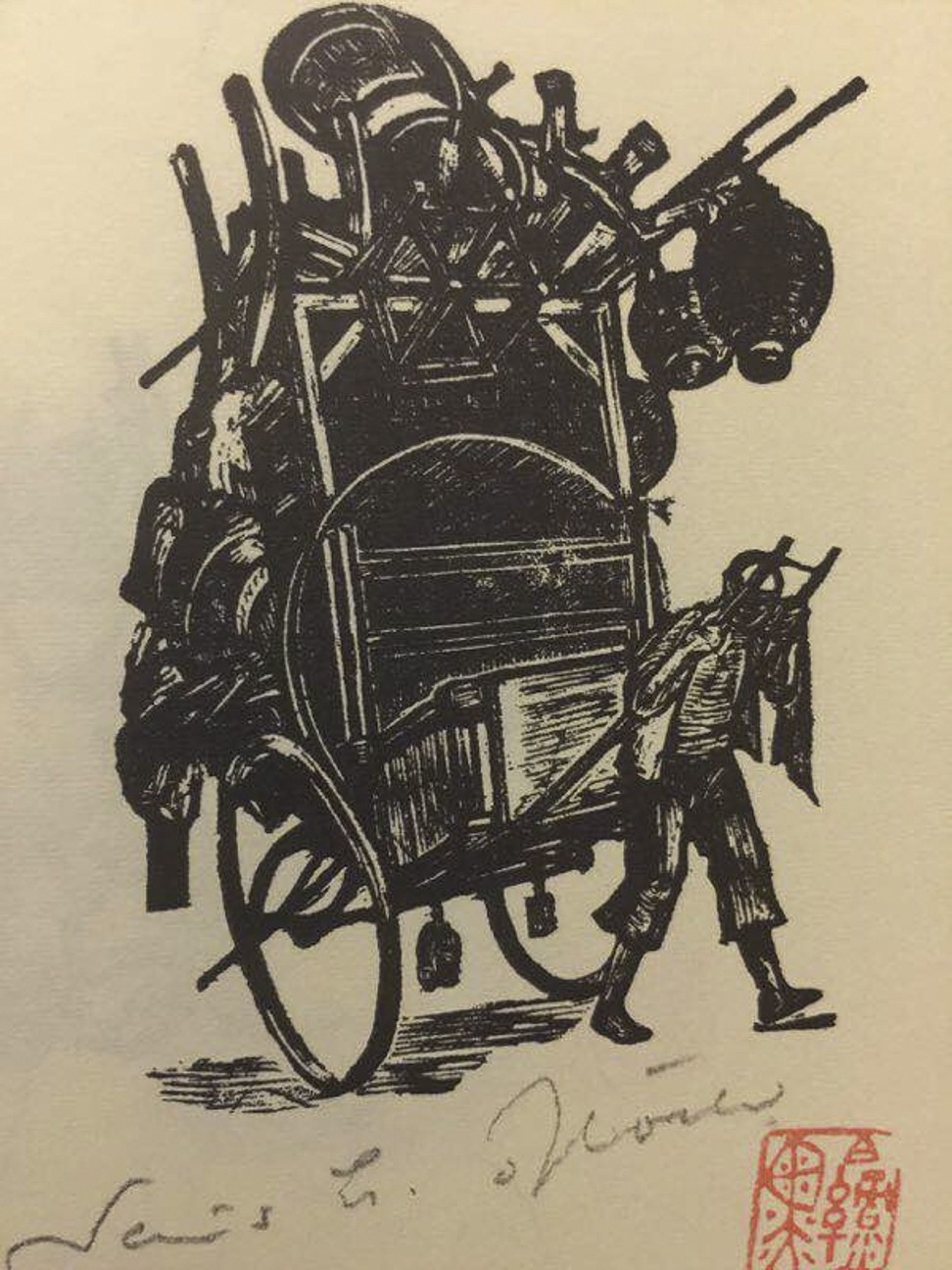

David Bloch, who died in 2002, is known in the art world for his paintings and woodcuts, many of which document the Holocaust and the artist’s nine years as a Shanghai refugee. The Bloch family gifted 15 items to the museum two years ago.

“From a large perspective, it’s a story of spirit,” Bloch Jnr, 62, told the South China Morning Post.

“My father came here as a refugee, with nothing and no prospects. Chinese people welcomed him and [the city] was extremely generous to my family.”

Allowing his father’s art and tools – as well as a poster promoting an exhibition of some of them held in Shanghai many years ago – to go on permanent display was his family’s way of saying thank you to the city for its magnanimity, he said.

He said he hoped the gesture would help continue what he called the legacy of friendship between Jews and the Chinese people.

China’s government had shown considerable interest in publicising the story of Jewish refugees, Bloch said, adding that he was “happy to support” its efforts.

The artist and his family are also the subject of a new documentary by Oscar-nominated Chinese director Wang Shuibo, titled Who is David Bloch?

Wang told the Post that he had recently finished editing the film but that no date had been set for its release.

The collection includes 16 woodcuts, four pieces from Bloch’s acclaimed series depicting the lives of rickshaw drivers, and four more detailing his experiences in Dachau.

Bloch, who was born in 1910 in the southeastern German state of Bavaria, lost his parents when he was just a year old, and was struck deaf by an illness at the age of three. Despite his early misfortune, he went on to study printmaking and design at the Academy of Applied Arts in Munich.

Along with hundreds of thousands of other Jewish men and boys, Bloch was sent to Dachau on November 9, 1938, the first night of what became known as “Kristallnacht”, or the “Night of Crystal”, a wave of violent anti-Jewish pogroms which took place throughout Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia.

The name came from the broken glass from the windows of synagogues, homes, and Jewish-owned businesses that were plundered and destroyed in the violence.

At the time, Dachau was known as a concentration camp for political prisoners and a training centre for SS concentration camp guards. It was not yet operating as an efficient, large-scale extermination centre, part of a strategy used by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis to help kill millions of European Jews.

Although more than 10,000 people were interned at Dachau in the aftermath of Kristallnacht, most were released after only a few weeks or months – often after they proved they had made arrangements to emigrate from Germany, according to an article published on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Bloch was among those to be released, and he wasted no time in fleeing his homeland. After arriving in Shanghai in 1940, he lived a life of relative luxury compared with most other European refugees, as a result of his American cousin sending him US$10 a month.

The money enabled Bloch to live in the city’s French Concession, the premier residential and retail district of Shanghai, and to hire a boy to do his laundry and cooking.

That era ended in 1943, when the Vichy France government signed its foreign concessions over to the pro-Japanese puppet government in the Chinese city of Nanking. Pushed by their German allies, Shanghai’s Japanese military authority drove Bloch and his fellow Jewish refugees to a “stateless-refugee-defined ghetto” in the city’s Hongkou district.

Poverty then became a way of life for Bloch. “His best present was a quarter pound of butter,” his son said. “My father said he didn’t buy one piece of clothing for 10 years.”

But there was one major benefit of the artist’s new life in Shanghai: it allowed him to interact with people. When he lived in Germany, people were reluctant to talk to him because he was deaf, his son said.

“In the 1910s and 1920s, physical disability was seen as insanity and no one would talk to you,” he said. “So coming to Shanghai is a revelation for him, opening a whole world for him.”

In 1946, with the war over, David married Zheng Dixiu, a deaf woman who was born in Haining, in eastern China’s Zhejiang province, but whose wealthy family hailed from Shanghai.

The couple moved to the US in 1949 and later had two sons. Although Dean Bloch, the younger of the two boys, was born and raised in the United States, and where he works as a doctor, he said that because of his roots, he regarded Shanghai as home.

He said he also wanted one day to take his mother’s ashes to her hometown. Zheng died in 1987.

Challenging as it was, the Shanghai experience enriched his father’s art by giving him an opportunity to meet people from different social circles, Bloch said.

“It opened his eyes. As an artist, it’s good to see different parts of the world,” he said. “My father said he had three lives: one in Germany, one in Shanghai and one in America.”

Looking at his father’s work gave viewers a sense of the his irrepressible and optimistic spirit, Bloch said. It also revealed how he “turned all his pain and suffering into a deep appreciation of life and people”.

Ultimately, the message in the story of Chinese-Jewish friendship was that people were all the same, he said.

“We want the same things,” he said. “We want to be accepted. We want to be understood. We want to be loved. It’s the universal concept for all of us. In doing so, we can be connected as human beings.”