How China’s AI technology can help Twitter’s suicidal users

Researchers in Beijing have so far identified more than 20,000 at-risk Weibo users and made contact with them. Now they’re working with a US team

Chinese researchers using AI technology to prevent suicides on popular microblogging site Weibo are now working with academics in the United States to introduce it on Twitter.

The system has been used on Weibo for the past nine months, identifying more than 20,000 users who expressed suicidal thoughts and sending messages to them with a hotline number and online tools to get professional help.

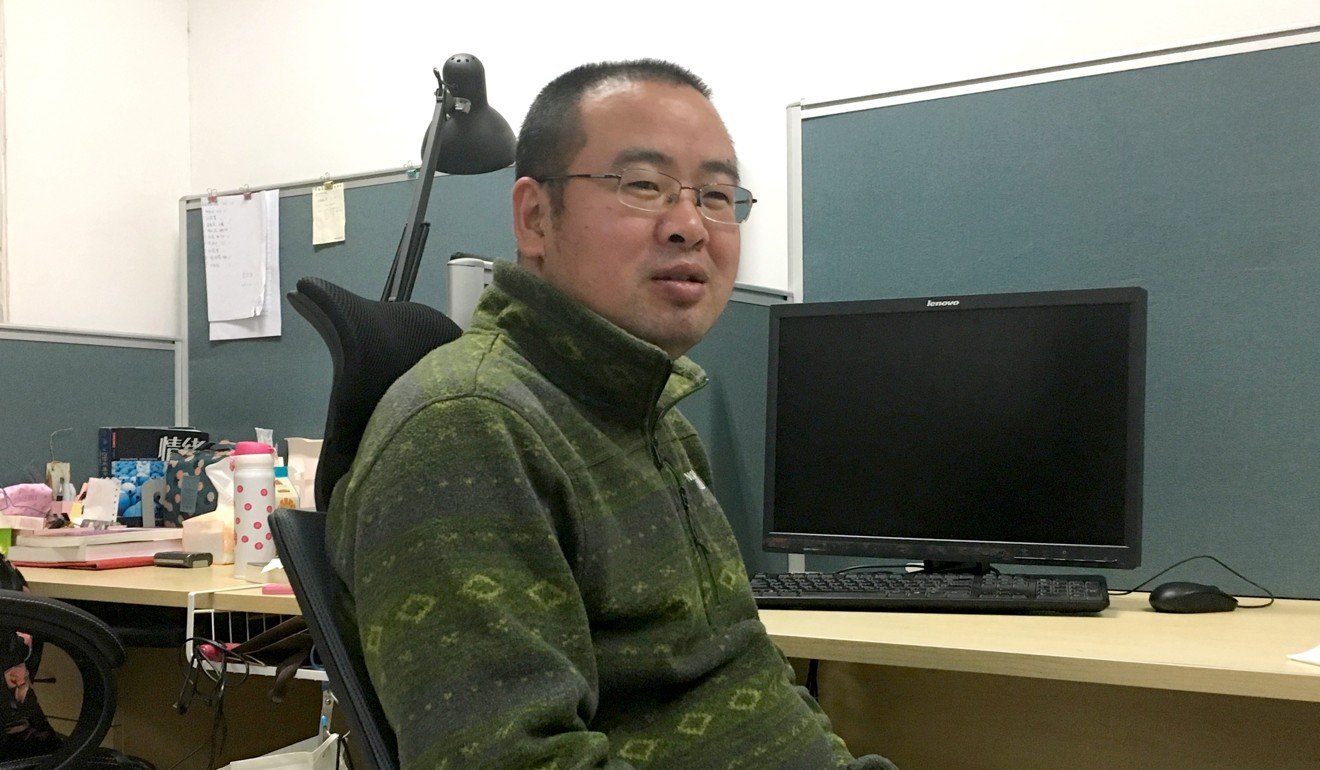

It was developed by a team led by Zhu Tingshao from the Institute of Psychology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

The team is now collaborating with researchers from Brigham Young University and the University of Maryland to extend the Chinese-language service to Twitter users with an English version, Zhu said.

The Chinese service is based on simplified characters, which are used in mainland China, but the team also plans to add traditional characters for Weibo users in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau, he said.

Zhu’s team began the Weibo trial around the same time Facebook started limited tests using AI to scan users’ posts for suicidal thoughts as part of a broader suicide prevention function. The social networking site in November announced it would expand the tool to all users in the United States.

Zhu said the team had contacted Weibo to introduce the AI system but it declined. Instead, the Chinese team uses data from Weibo – an open platform that had 381 million monthly active users last year – independently of the Nasdaq-listed company, communicating with targeted account holders as a Weibo user itself. This approach will also be used by the US researchers on Twitter.

The AI system uses a web crawler to scan posts and pattern recognition to find those that show suicidal tendencies. It does not look for keywords, but uses a prediction model that makes a judgment about the content, Zhu said.

Users deemed to be at risk are then sent a message offering mental health resources.

“We may not be able to make all of them change their minds about suicide, but we can at least offer some help,” Zhu said.

He said many people tended to go online to communicate their feelings rather than talking face-to-face with a specialist, and Weibo was one place where suicidal thoughts were expressed – especially in comments on other people’s posts that were less likely to be seen by acquaintances.

One source for the AI system’s machine learning was the more than a million comments made under the posts of a university student from Nanjing who committed suicide in 2012.

The student’s last update was on March 18 of that year, and people are still adding new comments every day – many use it as a place to share their innermost thoughts.

“I’ve got depression, so I want to try death. There’s no important reason for it. You needn’t care about me going. Goodbye,” reads the student’s final message.

Many of the comments that follow involve suicidal thoughts. A comment left on Thursday reads:

“See you in 100 days, because I’m as tired as you were. I finally figured out what you were thinking the second before you left.”

The system is designed to identify posts such as this one from people who are potentially at risk, and they are then screened by one of the researchers, Zhu said.

The authors of the posts are then sent a message from the team’s Weibo account, PsyMap, reading: “We saw your post. How are you doing? How’s your emotional state? … Everyone comes across different kinds of problems, and these problems can be solved.”

They are also sent a hotline number, run by the Huilongguan Hospital in Beijing, a psychiatric facility, and links to online counselling tools developed by the team.

Those who reply are put in touch with volunteer psychotherapists via text message to protect the user’s privacy, Zhu said.

He provided a couple of positive responses from users from when the system launched in April.

“Thank you. You are the first person to ask me this question,” one user replied.

“Thank you for giving me a hand when I’m sinking in the mire,” another wrote.

Zhu said of the 20,000 users they had contacted so far, about 4,000 had replied but 8,000 people had accessed the online counselling tools.

“So although less than 20 per cent of people we have contacted sent a reply, about 40 per cent of them did actually make use of the online counselling,” he said.

But some people did not want to receive the team’s messages and reported them to Weibo. As a result, PsyMap is restricted to sending a maximum of 200 messages to other Weibo users per day. Zhu said he had spoken to the company about the cap but it would not remove it.

Zhu, who has been researching suicide in China since 2014, said most of the people who expressed suicidal thoughts on the popular microblogging platform were young, and they were seeing more middle school students at risk.

In one case, a teenager wrote in a post that he was taking a train to the desert in the northwest and asked online users to let him “grow or die”. He later replied to a message from PsyMap and the team managed to make contact with him and get his parents’ contact details. They then called his parents and the teenager was found and taken home.

“We don’t expect to prevent people from committing suicide with a piece of software, but we can do something by identifying and paying attention to the early warning signs,” Zhu said. “We want to reach out to more people.”