China’s secret 1960s mission to send two dogs into space

Academy reveals how it selected the animals and strapped them into tiny, windowless capsules mounted on rockets for a journey they somehow survived

It’s 1966 and at a secret military base in southeast China, a small dog called Little Leopard is about to be sent into space.

Scientists carefully place the two-year-old animal, known as Xiao Bao in Mandarin, into a basket and hoist it up to a tiny capsule mounted on a T-7A rocket.

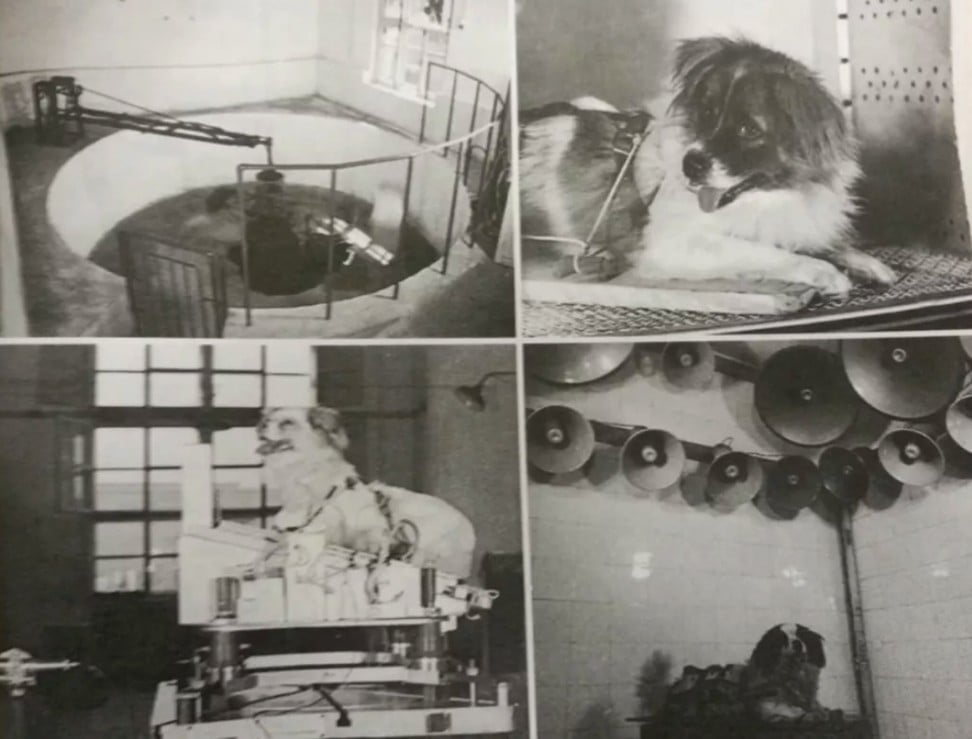

He was selected to join the mission in Guangde county, Anhui province from more than 100 puppies bred from star performers in an animal circus. They were chosen for their looks – the scientists insisted they had to be “cute” – and put through a series of tests that included being shut in a room and subjected to noise at more than 100 decibels to see whether they could tolerate the sound of a rocket blast.

It was too much for most of the puppies, but Little Leopard and three-year-old Shan Shan – both mixed-breed – emerged as the toughest, most intelligent and bravest of the lot.

But the scientists had overlooked a significant area when they were assessing the dogs, which became apparent soon after the basket left the ground. Little Leopard started to panic – he was afraid of heights. His handler said it was a struggle to get the frightened, shaking animal to the hatch for take-off and she could see the fear in his eyes.

Little Leopard and Shan Shan, who went through the same ordeal days later, were the first and only large animals used by China to gather biological data for the human space flight programme. But both missions were beset by problems, and neither reached orbit.

Both dogs survived the harsh conditions that could easily have injured or killed a human astronaut.

But after the experiment, the Chinese space authorities decided not to follow in the footsteps of the Americans and Russians, who had already sent many animals into space. Some of them never returned, such as Laika, a stray dog from Moscow who was the first to be launched, in 1957.

The unsettling details of China’s secret programme to launch dogs into space more than half a century ago were revealed last week in an article published on social media by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

To usher in the Year of the Dog, the academy, which oversaw the programme, said it wanted to “commemorate their legendary journey into the sky”.

On the day of that journey, Friday July 15, an apprehensive Zhao Xiuhua arrived at the military base with Little Leopard. The 21-year-old had been preparing for the launch, but when she was summoned with her dog to the platform, the height of the rocket – about the same as a 20-storey building – was a challenge. Zhao said later that the dog had never encountered anything so high during training, and neither had she.

They were both scared, and Zhao held the desperate animal in her arms trying to calm him down, patting him and gently talking to him.

Eventually he did calm down, and allowed the scientists to strap him into the windowless capsule full of monitoring equipment. They were most interested in changes to his breathing, circulation, heart rate and body temperature at various stages of the flight, and a sensor was inserted in the main artery of his neck to get precise readings of his blood supply to the brain.

The small, one-tonne rocket blasted off. The T-7A, a research rocket based on rudimentary technology, had been used to transport spent equipment to the edge of the atmosphere – it was not designed with the comfortable or safe journey of a passenger in mind.

Little Leopard, strapped tight inside the capsule, endured unspeakable pain and deafening noise in the 20 minutes that followed. The force of acceleration was up to 12 times the pull of gravity, causing pressure, or G-force, that prevented the dog’s heart from pumping enough blood to his head.

Most humans would have passed out from the oxygen shortage at four or five Gs, and no astronauts have experienced more than eight Gs during a space flight.

There were huge fluctuations in Little Leopard’s biometric data, the academy said, which could have been caused by the g-force, violent shaking of the capsule, heat, fear or sheer panic.

Some 20km (12 miles) before it reached low Earth orbit, the capsule was ejected by the rocket at an altitude of 80km and it parachute-landed on a mountain about 40km from the launch site.

And when he was fetched by helicopter and brought safely back to the site to be reunited with his handler, a crowd had gathered and Little Leopard was given a hero’s welcome, according to the academy.

Two weeks later, Shan Shan was put through the same process on another T-7A. But her journey was worse, and the huge shock waves generated by the rocket engine wrecked the monitoring equipment, so there was no data for her. Again, the rocket did not reach orbit.

But Shan Shan also survived the mission, and both dogs were returned to Beijing where senior government officials presented them with honorary awards.

It is not known what happened to the dogs after that, as the whole country descended into chaos and violence during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

The academy also revealed that it had tried to use monkeys for the mission but gave up because they were “too active” – they were banned from Chinese space programmes after causing havoc in research facilities too many times.

One researcher involved in China’s manned space programme said the country had used far fewer animals than Russia or the United States have in their space experiments.

After launching about a dozen mice and rats and the two dogs into space, the authorities decided not to send any more large animals because the data was not reliable.

“The fluctuation of data can be seen but the exact cause can’t be identified,” said the researcher, who requested not to be named due to the sensitivity of his job. “Animals can’t talk – they can’t tell us whether they feel pain or if they’re panicking.”

China carried out several unmanned launches of its Shenzhou spaceship before sending its first man into space, Yang Liwei, in 2003. These unmanned missions used dummies that were wired with sophisticated sensors designed to simulate the presence of an astronaut and collect information.

More than 10 Chinese astronauts have since been sent into space, and Beijing’s multibillion-dollar space programme includes a goal of having a crewed space station by 2022.