Grinding poverty in China – is Xi Jinping’s alleviation campaign making any difference?

Families struggling to keep their heads above water in one mountain village say they’ve received some help from the authorities, but it’s their children they’re counting on to improve their lives

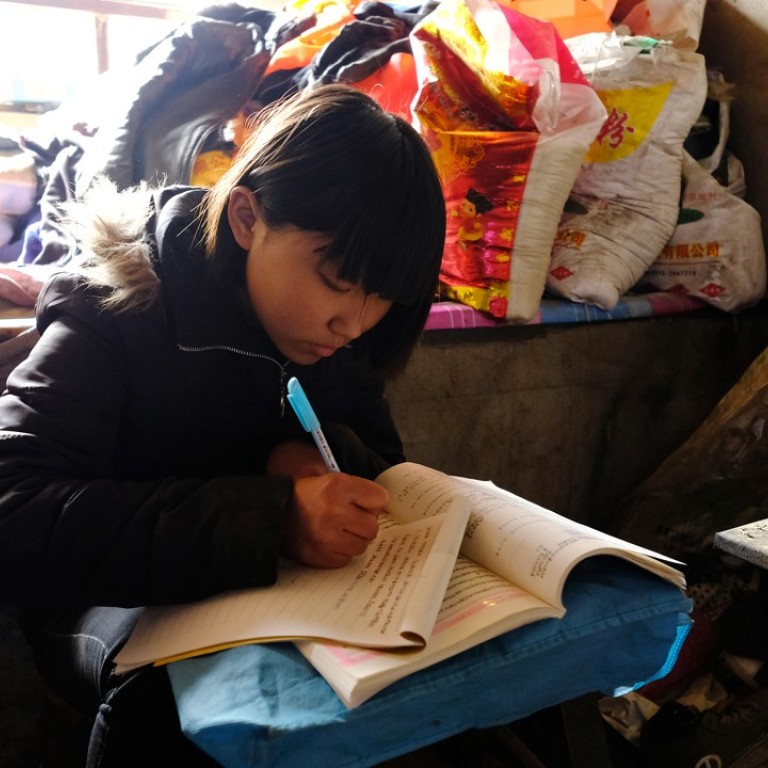

In an impoverished mountain village in northern China, “Xiao Zhang” – or Little Zhang – is doing her homework.

There is just one stool to sit on and no table at her family’s run-down home, so the 15-year-old perches on a tree stump on the cold concrete floor, using the stool as a desk.

Little Zhang spends her weekends at home with her family, studying and helping her father to look after her mother and 18-year-old brother, both of whom have mental disabilities and cannot take care of themselves.

During the week she attends a boarding school in the township, with the help of a charity, working towards her goal of getting into university and eventually landing a job in a big city like Beijing.

It’s not just her dream – her father Zhang Liansuo is counting on her to look after the family down the track.

“My only hope is for my daughter to do well at school and go to university,” the 58-year-old said. “Her mother and brother will depend on her when she’s older.”

Life is tough for this family in Xiaoguancheng, Hebei province, where Zhang makes a meagre living as a corn farmer, sometimes picking up extra work as a labourer to make ends meet.

But although Little Zhang is under huge pressure, she says it motivates her.

“I don’t feel bad about my family background. If anything, it makes me more competitive with my classmates. If they can recite an ancient essay, I think I can do it, too,” said the teenager, who is in Grade Eight.

“I don’t know what I want to study at university yet. Right now I just need to get into the best high school in the county, then into university so I can get a good job.”

Here in the foothills of the scenic Taihang Mountains – about an hour’s drive from Laiyuan county and three hours west of Beijing – the modernity and development of the cities is a world away.

The village was the first base for the communist-led army during the Sino-Japanese war and the civil war, but its significance as a revolutionary stronghold means little now. It has remained a poor rural area while the urbanised parts of China continue to make economic strides.

Technically, the village sits above the official poverty line of 2,300 yuan (US$360) – its per capita income was just under 3,000 yuan in 2016.

But when President Xi Jinping vowed to wipe out poverty back in 2015, villages like Xiaoguancheng were the focus for the campaign.

Beijing has set 2020 as the year that no Chinese should be living below the poverty line, aiming to become a “moderately prosperous society”.

More than 30 million people were still living below the line in the second half of 2017, but the government has projected that at least 10 million people will be lifted out of poverty this year.

It says over 68 million people have risen out of poverty in the past five years.

So far though, it seems not much has changed for the Zhangs and other villagers. With just two years to go to achieve the ambitious target, many of China’s rural poor still rely on government handouts and the generosity of friends and relatives, or, like Zhang, their children getting a good education so they can land a well-paid job somewhere else.

The Zhangs’ home was built 30 years ago and remains unpainted and barely furnished. A line of persimmons dries in the sun on a windowsill, bright orange against the drab grey exterior. They have two electrical appliances – a 20-year-old washing machine, which sits outside, and a second-hand television bought nine years ago.

Inside, the two-room home is dark and spartan. The walls are cracked and mouldy, while bags of clothes and bedding are piled high on one of two traditional brick beds, or kang, which are commonly found in northern China. A wok and other basic kitchen equipment are stacked on the ground beside a brick fireplace used for cooking, while a small coal-burning heater gets the family through the bitter winter months.

It is an uncomfortable, harsh existence, but Zhang said he was doing the best he could to look after his wife and children.

The family earns just 1,500 yuan per year from the two tonnes of corn they grow on their land. Zhang’s wife and son meanwhile receive an annual disability allowance from the government of 2,000 yuan each. Zhang said his luck changed when he was offered a fire patrol job in the mountains this winter, paying 8,000 yuan a year. But he is not sure if it is just a one-off contract, and either way the family will continue to struggle financially.

They eat simply, with corn as the staple. Zhang sells some of the harvest in exchange for wheat and rice, and they grow their own cabbage, potatoes and carrots. Meat is a special treat reserved for the holidays.

“Our biggest expense is my daughter. It costs 50 yuan every week for her transport, food and the other things she needs for school,” Zhang said. “But I won’t let her go to a vocational school or marry young – she needs to go to university.”

Little Zhang has attended school for the past six years with the help of charity organisation Boyou Commonwealth Group. She is focused on her studies, and her sights are firmly set on a future beyond the mountains – China’s big cities are calling.

She was inspired by a trip to Beijing in 2015 to celebrate her birthday, paid for by the charity group, and particularly a visit to the planetarium.

“I saw and learned a lot in the big city. I got to spend time in a different environment and meet new people,” she said. “It’s so different from being in a small village where everyone knows everyone.”

But for other families in the village who want to send their children to university, the tuition fees and living costs are out of reach, and their access to government support is limited.

Wang Sheming, 64, sees his son’s education as an investment. He has borrowed money to pay for his son to attend university in Baoding, a city in the province, where he is in his second year majoring in equipment manufacturing.

“I sold my corn harvest this year for 1,500 yuan. The seeds cost me 240 yuan, and the fertiliser was 300 yuan,” Wang said. “I worked some odd jobs too and made 500 yuan, but my son’s living expenses alone are around 10,000 yuan a year – how can I cover that?”

His son’s annual tuition fees of 7,000 yuan were paid for by Boyou, the same charity that funds Xiao’s education, and Wang borrowed money from relatives and friends to cover his living expenses.

Wang said he was too old to move to the city as a migrant worker and he needed to stay in the village to take care of his 90-year-old mother.

Although they are officially recognised as a family living under the poverty line, Wang said he did not get much government support. A state-owned company tasked with helping the village sent the family 10 kilograms of rice and a bottle of cooking oil, he said, and that was it.

“I was told to find some means on my own, such as raising a cow or something, to improve the situation. But I’d need at least 7,000 yuan to buy a cow,” Wang said. “I don’t even have the money to buy a cow – and I don’t have any collateral for a loan.”

Like fellow villager Zhang with his daughter, everything is riding on Wang’s son getting a university education and finding a job – and he believes that if the government could provide some financial support for that, the family could have a real chance of turning their situation around.

Meanwhile, another villager said she was having sleepless nights as the family’s debts mounted. Zhang Yanli, 50, has had to borrow 50,000 yuan to pay medical bills and school fees since her husband had a stroke seven years ago, leaving him partially paralysed.

They sell eggs from their 10 chickens but it is far from enough to cover their costs, especially with their 21-year-old son studying at a vocational college, and their daughter, 11, at a boarding school.

Her husband, 55-year-old Zheng Gang, receives a disability allowance of 2,000 yuan every year, but that does not even cover his medical costs.

“I’m very grateful for the 2,000 yuan allowance, but I guess I’ve just given up on the possibility of a life where we’re not struggling so much. We’ll be happy enough if our situation doesn’t get worse,” Zheng said. “And hopefully my health will improve so I’m well enough to work.”

The South China Morning Post will return to Xiaoguancheng periodically until 2020 to see whether Xi’s poverty alleviation campaign is having any impact on the villagers’ lives.