Life is no bowl of cherries for this Chinese pear farmer, but he presses on with his ‘green dream’

Eviction, snow and a larcenous sales agent have all plagued Sun Yongjiang’s pursuit of a business built on natural pest control practices

For Sun Yongjiang, life as an environmentally friendly pear farmer has turned out to be a lot like a fruit basket: full of things both sweet and sour.

He has weathered numerous setbacks, from an unexpected snowstorm that ravaged his crop and wiped out a year’s profit to an agent that left him high and dry after taking his money.

But supported by his loving family and scores of fans on the internet, he remains committed to an enterprise built on natural pest control practices at a plantation about 100km (62 miles) from his home in Korla, a medium sized city in western China’s Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

“I had not imagined that the life could become so difficult,” Sun told the South China Morning Post about his struggle to bounce back from a cold snap that devastated his pear flowers this spring.

“My wife tried to persuade me to give up but I still don’t want to. Green-style planting is the right thing to do.”

Sun was born and raised in Xinjiang. When he began growing pears a decade ago, he followed the convention of selling his fruit to wholesalers.

But the wholesale agent’s low prices bothered him, so he took a bold step: he decided to manage the wholesale business on his own.

Initially, Sun targeted markets in Changsha, in central China, and in Guangzhou and Shenzhen, to the south. But four years ago, convinced he had a product tailor-made for an emerging segment of the population that craved high-end fruits, he took the plunge and made Beijing his primary market.

The timing seemed perfect. China’s middle class had reached 300 million people – or nearly one third of the segment globally – as the nation’s economic stability, urbanisation, emerging new hi-tech industries and an improving services sector boosted demand for clean air and healthy foods.

Sun’s pears used no chemical fertiliser and had “very good” pesticide detection test results, allowing them to exceed the capital’s quality standards, he said.

He became convinced to push ahead with his Beijing focus after talking with members of a Beijing supermarket group he took on a tour of Aksu and Turpan, two famed Xinjiang fruit-growing regions, and friends and fellow farmers.

But things quickly went awry. He found an agent in Beijing to sell 500 parcels of pears that winter. Then he drove 3,700km from Xinjiang to Beijing with another 5,000 parcels.

He never saw the agent again – or any money.

But he stayed the course. Through friends who used WeChat, China’s version of Twitter, he learned his pears were becoming popular in Beijing.

“We started to work at five o’clock in the morning,” he said. “My wife was busy handling phone orders and I drove around the city delivering pears till very late in the evening. We even worked on the eve of the Lunar New Year,” he said.

Success moved him to sell the pears produced on his 4.7 hectare (11.6 acre) “green-style” plantation via WeChat, touting his commitment to natural cultivation methods.

“I have done pesticide detection tests at Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences for the past three years,” he said. “No chemical pesticide. It is natural. It is green.”

He installed cameras at the farm that webcast the cultivation process and he chronicled the progress in near-daily photo posts on WeChat.

But his intense focus on caring for the land and his crops left Sun feeling guilty about giving too little time to his children.

While he took care of business, his mother took care of his 15-year-old son and his mother-in-law babysat his three-year-old daughter.

Sun’s fortunes took a turn for the worse last year.

In November, he was among the migrant workers that authorities ordered to leave thousands of houses after a fire at a building in Xihongmen, Daxing district killed 19 people. He ended up moving to a property with a higher rental fee.

His eviction also delayed his sales plan for that year, hurting his bottom line. Although Sun earned 60,000 yuan in 2016, he said he saw no profit in 2017.

The disruption also forced him to pass up a Spring Festival celebration with his family at home while he looked after his business in Beijing.

“My wife brought my little girl to be with me,” Sun said. “I missed her very much. They were sweet days, having her at my side,” he said.

He tried again to revive his plantation operation. But early April snowstorms and frost dealt a blow to this attempted U-turn in his suddenly faltering career.

“The bad weather destroyed all the pear flowers,” he said. “Basically there will be no production this year.”

To offset his crop and land losses, he tried raising 500 geese. But a cold spring killed a fifth of them.

Thinking of his WeChat followers motivated him to stick with his unpredictable profession.

“I have 3,000 followers of my WeChat,” he said. “They trust in me and my goods. I cannot let them down.”

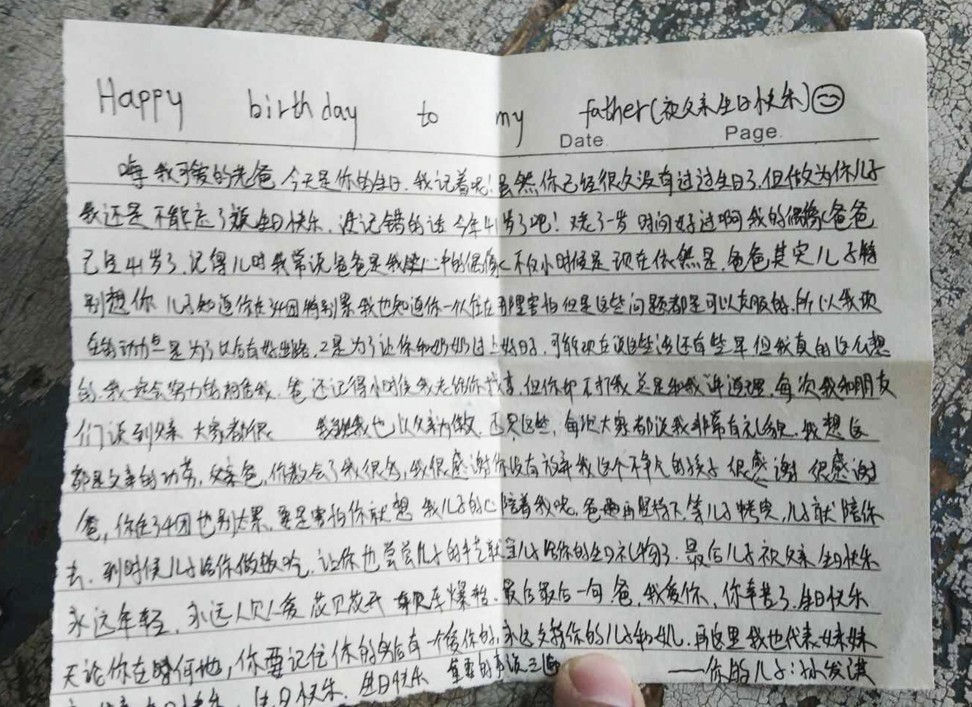

But a note his son sent him for his birthday last week, touting his persistence, empowered him like nothing else.

“Dad, you are my idol,” and have been, since I was a little boy, the note said. “And you are 41 years old.

“I miss you very much,” the note said. “I know you are very tired there and you are also afraid of being alone. But all these can be overcome.

“I am proud of you … You taught me a lot.”