Could these be the faces of the murdered wife and son of China’s first emperor Qin Shi Huang?

Facial reconstruction technology helps bring back to life two possible victims of a notorious royal massacre whose dismembered remains were found at the site of the terracotta warriors

Chinese researchers have reconstructed the faces of a young man and woman who could be one of the many sons and consorts of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China – and who may also have been victims of one of the most notorious and gruesome purges in Chinese history.

The dismembered body of the young woman, who was about 20 years old, was found in a group of around 100 tombs in the emperor’s mausoleum in Xian – home to the famed terracotta army.

All the bodies in the tomb are young females and the archaeologists believe these women could be the emperor’s consorts and their servants, judging from the class of the graves and burial items found there.

China urges US to get tough on man who stole thumb from US$4.5 million terracotta warrior on display in a Philadelphia museum

Some of the bodies had been dismembered and placed outside passageways leading to the burial chambers that were thought to have contained their mistresses’ bodies.

It is thought that the women may have been killed as part of a human sacrifice following the emperor’s death and the evidence suggests the executioners made no concession to age or rank.

Researchers have reconstructed the face of one of the high-status women in the tombs – possibly a wife or concubine of the emperor.

According to a facial reconstruction photo provided to the South China Morning Post, she had a pair of rounded, large eyes and long, defined nose.

The computer-generated portrait used a deep learning algorithm and large anatomic database to reconstruct her features, although details such as her hair style and eye colour can only be guessed at.

The same technology has been used for forensic facial reconstruction in police investigations across the country.

Intriguingly, her features do not appear to be typically Han Chinese. Instead they suggest a possible central Asian or even European ancestry – a possibility that could prompt intense academic controversy.

Chinese tomb raiders sent to prison for theft of ancient relics

The Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor in the northwestern province of Shaanxi is the largest tomb on earth.

Its surface and underground structures extended over an area of more than 56 sq km (21.6 sq miles), or 78 times the size of the Forbidden City in Beijing.

The site is world famous for its army of terracotta warriors, but the core architecture of the 76-metre pyramid-shaped mound which houses the emperor’s coffin and treasures remains largely unexplored.

The male skull came from a separate cluster of tombs in Shangjiao village on the eastern outskirts of the mausoleum.

A bronze arrow head was found in the right temporal bone at the base of his skull, providing an obvious clue as to how he died.

His head and limbs had been separated from his body and then placed on top of a treasure box in a multi-layered coffin.

The remains of other young men and women found in nearby tombs had been similarly dismembered.

They had been buried with a large number of valuable artefacts, including ceramics, jade accessories, silks, bronze swords, silverware and gold bars – which suggested a high social rank.

Some researchers believe that these bodies may include members of the imperial family who were murdered in an extensive purge soon after Emperor Qin’s death.

The possible Qin prince, according to the facial reconstruction, appeared to be a man about 30 years of age with olive-shaped eyes and a pronounced nose.

Li Kang, an associate professor at the School of Information Science and Technology at Northwest University in Xian, where the facial recognition software was developed, said: “We have confidence in our results.”

The technology has been rigorously tested and widely applied in crime investigation by the Ministry of Public Security and, said Li, “requires little human intervention”.

But the results have prompted some debate among archaeologists.

The faces, especially the woman’s, appeared to show more ethnic divergence than would typically be expected in Han Chinese people.

Some researchers have speculated that the women might have “Western” origins – possibly Persian, or even European – but others believe this is improbable.

Professor Zhang Weixing, lead scientist of the facial reconstruction programme and head of the research department at Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, said he did not think the woman looked like a Westerner.

“It is too early to make a conclusion without further, more solid evidence,” he said.

The museum was planning to carry out DNA testing on these two and other remains and hope to come up with more clues about the ethnic composition of the Qin court.

Zhang also said that not all archaeologists were convinced that the bodies were of the emperor’s son and consort, arguing they may well be senior court or government figures.

Zhang said the main purpose of the facial reconstruction programme was to bring “an important chapter of Chinese history to life”.

He added: “It will give people an intuitive feel to what happened in recorded history.”

Qin Shi Huang commanded one of the most powerful military forces in the ancient world and conquered all the rival kingdoms to form the first unified Chinese state.

Qin Shi Huang, who did not have an official empress, had selected a large number of beautiful young women from across the country as his consorts.

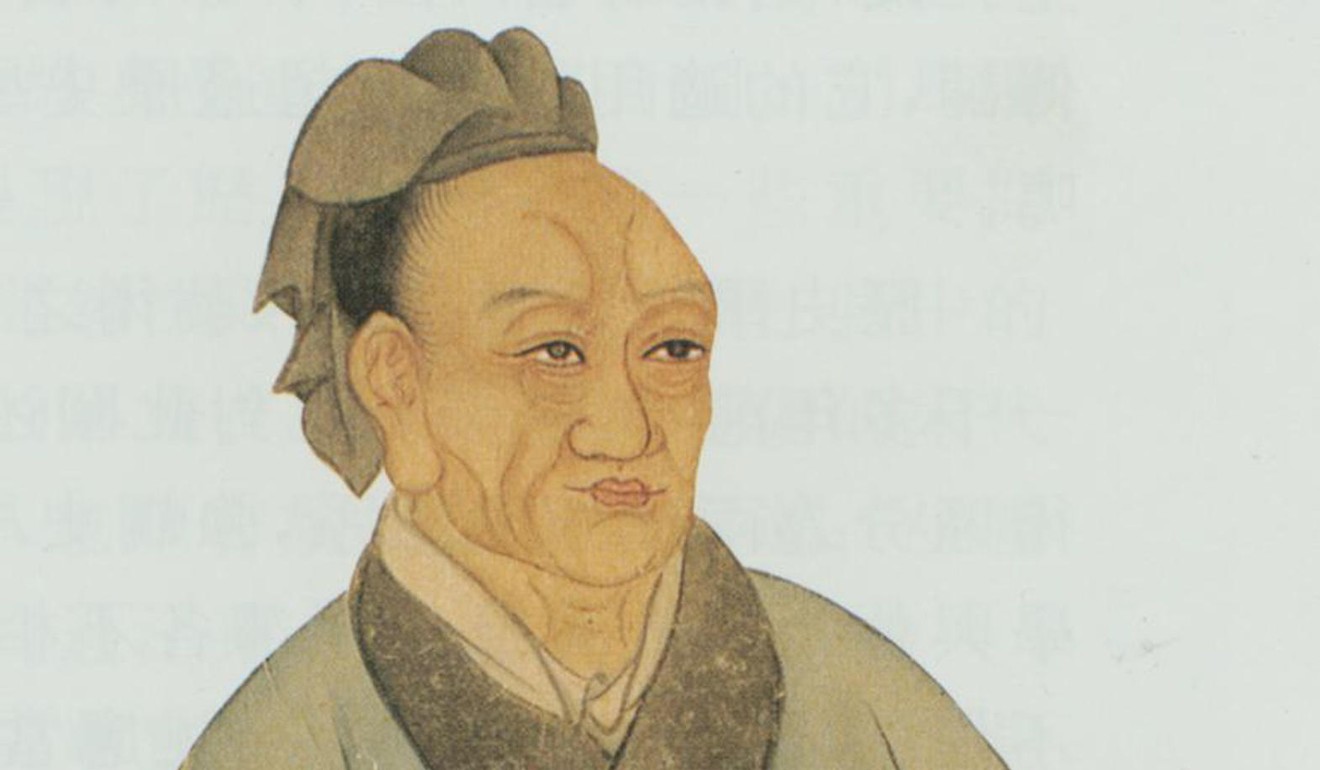

These women gave birth to around 40 sons and daughters, according to Sima Qian, a historian living in Han dynasty about a hundred years later.

After the emperor’s death in 210BC his younger son Hu Hai seized the throne by covering up his father’s death and forging his will to force his older brother to commit suicide.

He then gave an order that any of the late emperor’s consorts who had not given birth to children would not be allowed to leave the palace alive.

According to Sima a “large number” of these women were sacrificed and buried in the mausoleum. Other accounts claim some victims were buried alive, although no evidence to support this has been found.

How to enjoy the Great Wall of China’s wild side: tips and drone footage from an expert

Then Hu Hai moved on to persecute his siblings, as he feared they would challenge his legitimacy.

Eighteen princes were publicly executed and their bodies put on display while four princes were forced to take their own lives.

Nor did Hu spare his sisters. According to Sima’s account, 10 princesses met gruesome deaths.

Their limbs were cut off one after another, and they were left to suffer for an extended period before the executioner slit their throats.

In total more than 30 sons and daughters of Qin Shi Huang died in the purge.

Some historians have described it as the worst political murder that ever happened to a royal family in Chinese history.

Hu himself spent just three years on the throne before being overthrown after a catastrophic military defeat and the empire quickly crumbled.

Zhang Zhongli, a senior archaeologist at Shaanxi Archaeological Institute in Xian, said Sima Qian’s accounts were “quite reliable”.

As a government historian, Sima had direct access to official archives from the Qin empire.

He selected his sources with care, and an increasing amount of archaeological evidence found in or near the mausoleum site in recent decades supports his account of some important events, Zhang said.

Although the woman’s facial appearance may suggest she had non-Han origins, there is not enough evidence to draw any firm conclusions and the suggestion that people with Western origins may have reached the Qin court is likely to be subject to intense academic questioning.

Zhang conceded it was possible that some travellers from the West had reached the Qin empire and that the imperial court had a degree of ethnic diversity.

Following the conquests of Persia and parts of India by Alexander the Great a century earlier, his Greek successors had established a European presence in central Asia.

But Zhang argued it was unlikely that there were extensive or regular contacts between China and the West at the time.

“Such a hypothesis is not supported by existing historic documents and archaeological evidence. Intercontinental journeys back then were extremely difficult due to the limit of transports.”

The arrival of visitors from the West or the Near East would have been a rare event and possibly the result of unusual circumstances.

A DNA analysis conducted by a research team in Fudan University, Shanghai 10 years ago on remains found in a pit for labourers near the site showed that they came from all over China.

The mausoleum was built by a workforce consisting 700,000 people, according to Sima.

The Fudan study suggested that most these people may have come from southern China and consisted of Han people and many ethnic minority groups.

Most had died from overwork or from disease.

Chinese chronicles claimed Qin Shi Huang was a direct descent of the Hua Xia, a major tribe of Han ethnicity in pre-historic times.

His family are then said to have moved from the mid Yellow River region to the western part of China and established the kingdom of Qin.

His tomb has never been opened since it was rediscovered in the 1970s and there have been no reports of any DNA tests being carried out on the remains of other possible members of his family that could yield more clues about the Qin’s origins.

Beijing plans to move 15,000 villagers away from its 600-year-old Ming tombs

According to Sima Qian, the tomb was built to continue the emperor’s rule in the afterlife. As well as the terracotta army it contained “palaces and scenic towers for a hundred officials”, enormous amount of treasures, and was defended by booby traps that would fire arrows at intruders.

The ceilings inside the tomb were decorated with heavenly constellations to the simulate sky and it contained a recreation of two of China’s main rivers, the Yangtze and Yellow River, made from mercury that flowed into a sea.

Archaeologists have partially confirmed the final claim after they detected abnormally high levels of mercury under the mound.