Strait ahead: how Beijing is planning world’s longest rail tunnel to link Taiwan to mainland

Scientists agree on blueprint for what would be the world’s longest rail tunnel but politics means it is likely to remain a pipe dream for now

After years of debate, Chinese scientists are close to a consensus on the design for what would be the world’s longest undersea railway tunnel, connecting the mainland to Taiwan.

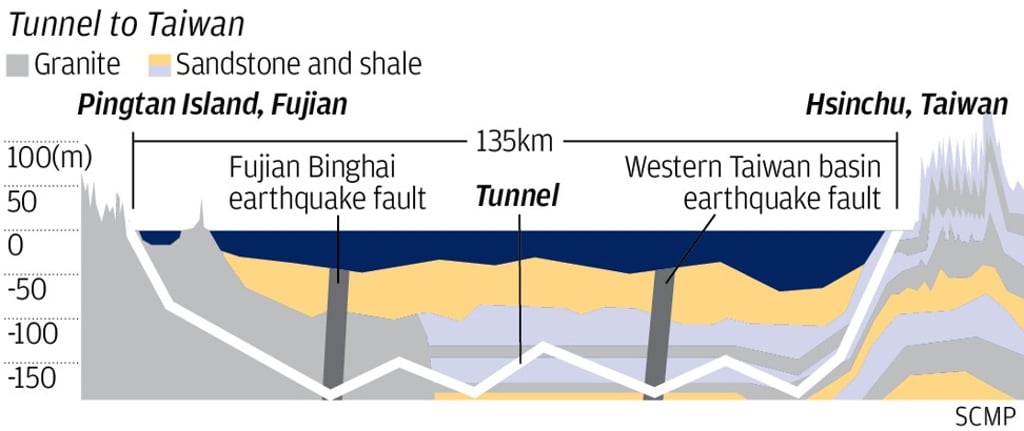

If realised, shuttle trains could be whizzing through a 135km (84 mile) undersea section of the tunnel at up to 250km/h (155mph) by 2030.

The ambitious undertaking would include a multi-billion-yuan engineering and technical “warm-up” project, according to plans the scientists have sent the Chinese government, the South China Morning Post has learned.

Despite this technological progress, rising political tensions between the self-ruled island and Beijing, which regards it as a renegade province, mean that the scheme is unlikely to come to fruition any time soon.

However, some researchers said it was possible that Beijing would start work on the project in a unilateral, and largely symbolic move.

Politics aside, surmounting the project’s technical tests would be a huge coup for China’s scientific, engineering and construction corps, analysts said.

“It will be one of the largest and most challenging civil engineering projects in the 21st century,” said a government scientist who asked not to be named because of the project’s sensitivity.