Chinese consumers’ crazy rich demand for rosewood propels drive toward its extinction

Stronger international regulations are doing little to stop traffickers from illegal trade of the tropical hardwood

The purchasing power of China’s burgeoning middle class is the stuff of dreams for retailers, but is increasingly causing nightmares for conservationists.

Conspicuous consumption among wealthy Chinese on the mainland and throughout Asia caught the world’s attention with the runaway success of the film Crazy Rich Asians. Characters in the movie, whose sequel will be set partly in Shanghai, wowed audiences with their acquisition of high-end cars, real estate and jewellery.

However, an affinity among Chinese for another expensive commodity is calling attention to a matter that would not play as well in a romantic comedy: the largely illegal trade in rosewood, the world’s most highly trafficked wild product and one on the edge of extinction.

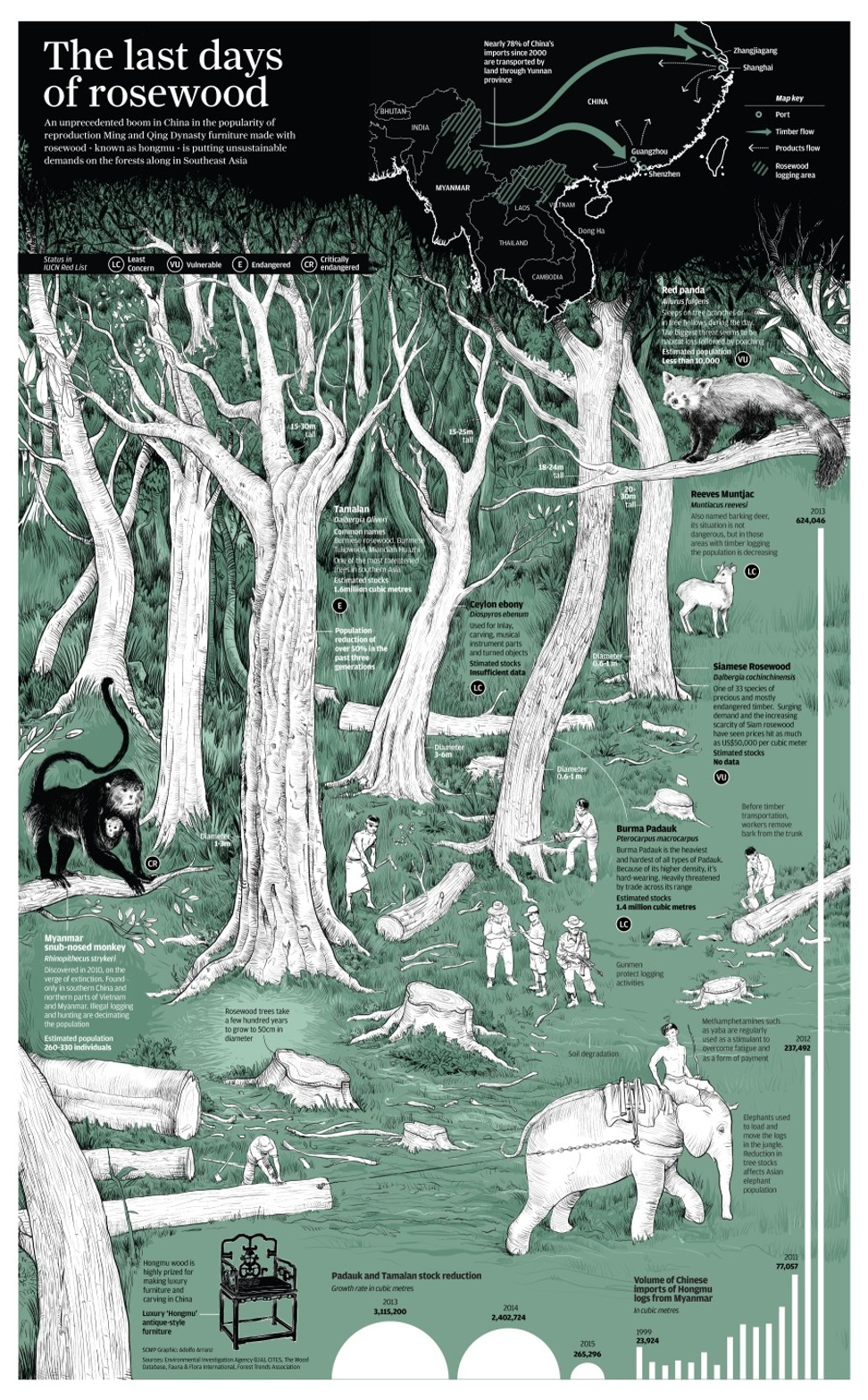

The tastes of China’s nouveau riche are driving demand for the rare tropical hardwood, which is prized for its use in replica Ming and Qing dynasty furniture. Known in Chinese as hongmu, rosewood is a fragrant, richly hued tree native to the tropics, from Southeast Asia to West Africa to Latin America.

Chinese rosewood furniture has been meticulously carved by craftsmen since at least the 10th century, but the wood came into its own during the Ming dynasty, when a unique joinery technique was perfected.

According to a collectors guide from Christie’s, rosewood furniture values derives value from both its “beautiful lustrous qualities” and its rarity, since it is “difficult to harvest and mostly found outside China”. Today, new rosewood furniture is valued for the quality of its timber, craftsmanship, nostalgic cultural value and as a collectable investment.

The tree is slow-growing, with a lifespan of several hundred years, and the rise in demand has brought numerous species of rosewood near commercial extinction. Furniture-makers have turned to Siamese rosewood in Southeast Asia, but as these timber stocks fell as well, traders have ventured ever farther afield for related species – to West Africa and, some fear, next to Latin America.

Currently, between 40 and 50 per cent of rosewood timber in the Chinese market originates in West Africa, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a global non-profit that tracks forest crime.

In 2000, the China State Bureau of Quality and Timber Supervision released the “national standard for hongmu”, which regulates the eight timber types that can officially receive rosewood classification.

Today, China is the only country with a specific customs code for the timber, with the eight types falling into 33 species of the dahlbergia family receiving official recognition.

But even this was not able to keep up with demand during the latest period of hongmu speculation from 2005 to 2014. By 2016, UN figures showed that seizures of illegally traded rosewood had reached 35 per cent of the global value of all wildlife seizures, more than elephant ivory and rhinoceros horns combined.

To protect the world’s dwindling supply, in 2016 more than 250 species of the hardwood were added to Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an international treaty of which China is a signatory. As a result, trading in those species requires additional certificates of sustainability to accompany their import and export.

According to the EIA, however, there are loopholes that allow traffickers to work around these requirements.

“You can forge the documents … and when one species is declared as another, you really have to be a timber specialist to recognise [them],” said Lisa Handy, EIA’s forest campaign director. The cut timber is hidden in shipping containers purposefully mislabelled as another product – or from another country of origin, where the wood can still be legally exported.

Exotic animal and plant species have historically fetched high prices in China as delicacies or for use in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

Research by the non-profit Wildlife Conservation Society has found that more than 1,500 animal species have been recorded as TCM ingredients, while 77 plant species – over a fifth of the 388 threatened species listed in the China Plant Red Data Book – are also used.

The world’s most trafficked mammal, for example, is the pangolin, a scaly anteater native to parts of Asia and Africa that is poached for both its meat and use of its scales in TCM. Other ingredients include rhinoceros horns, orchid parts and bear bile.

The difference between China’s historical and current appetite for wildlife, however, is the numbers. The global wildlife trade is worth an estimated US$19 billion a year, according to UN figures, and China is one of its largest markets because of its rapid economic development and new middle class.

The robust pace of China's economic growth between 1978 and 2012 created a massive middle class of 480 million people in 2018, a figure projected to increase to 780 million by the mid-2020s. For these nouveau riche, previously unaffordable products like rosewood furniture have become status symbols.

But along with the rise of conspicuous consumption is ethical consumption. Some conservation groups, like WildAid, which aims to end the illegal wildlife trade, are betting big on this second group of consumers. WildAid China has enlisted celebrities like former NBA player Yao Ming, film star Jackie Chan and actress Li Bingbing to raise awareness against trafficking.

However, Peter Knights, the CEO of WildAid, recognises that consumer demand is just a part of the picture; government regulation also plays an important role. “Sensible and well-enforced regulations provide critical safeguards for vulnerable and threatened wildlife species, and consumer awareness helps reduce overall demand,” he said.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, launched in 2012, showed that government action could decrease trafficking numbers.

The campaign fought conspicuous consumption by government officials – including ostentatious dinner banquets, where foods like shark-fin soup had long been menu staples. And the results have been positive: consumption of fin soup have decreased by up to 70 per cent, according to WildAid.

The CITES treaty also plays a role – but primarily in affecting prices, rather than availability.

“China wants to be seen as an environmental leader and show that it is a responsible country,” said Handy of the EIA. “With regard to CITES, China has taken steps to implement the convention by seizing or excluding some imports from tree species that are protected.”

But implementation is far from perfect, especially given the gap between international treaties and domestic legislation.

“No law exists that allows Chinese authorities to stop any timber that has been harvested or traded illegally outside of China,” Handy said. “This is a serious gap in governance. Even the most egregious cases of illegally logged timber can be laundered because importing illegal timber is not illegal in China.”

This is a major challenge for exporting countries like Guatemala, says Aura Lopez Marina, an environmental crimes lawyer who works for the Guatemalan government. She believes that China should do more to enforce CITES – otherwise the consequences are dire.

Though Guatemala and the rest of Central America account for just a fraction of the global trade of rosewood – less than 10 per cent, according to the EIA – the rarity of the trees means that even a small uptick in harvesting would be devastating. “It’s almost extinct,” Lopez Marina said.

And the increasing market demand, despite the CITES regulation, is already being felt.

Of the five major rosewood seizures by customs officers in Hong Kong this year, yielding a total of 114 tonnes, three shipments are suspected to have originated in Guatemala. And these are only the ones that have been discovered. The rest are bound for China’s high-end furniture markets and, from there, Chinese homes.