Exclusive | Why China is going all out to invent new, stronger, cheaper drugs … it’s not all about challenging the West

China’s big ambitions to become a powerhouse of pharmaceutical innovation is as much about the well-being of its people as it is about narrowing the gap with the West

China, home of Tu Youyou, winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize for medicine, is not known for its prowess in drug innovation.

This is despite it being the world’s second largest pharmaceutical market and owner of the second highest number of biotechnology and pharmaceutical intellectual property rights.

Since Tu and her team made their groundbreaking discovery of an anti-malaria medicine in 1972, only a few domestically developed inventive new drugs have won government approval to be marketed.

In the first 10 months of last year, out of 35 new drugs that received Chinese regulatory approval, just one was developed by a domestic firm, according to a report by business consultancy McKinsey. Three of the 11 drugs given the marketing green light in 2015 and 2016 were developed by local firms.

Keep calm and relax: China’s tech progress is only a national security challenge if we make it so

In the United States – the world’s biggest and most advanced pharmaceutical market – of the 46 new drugs given consent for marketing by regulators last year, 28 were developed by US firms and the realisation of all but four of the rest were led by European firms. None were Chinese.

“Drug innovation is still nascent in China but, following sweeping regulatory reform, it has been moving rapidly in that direction in the past couple of years,” said Marietta Wu, managing director of private equity firm Quan Capital and a co-founder of Shanghai-based drugs developer Zai Lab, which listed on the US’ Nasdaq market last year.

“Compared to the US, the innovation gap is still significant.”

BANKING ON INNOVATION

Beijing is determined to change that.

Its “Made in China 2025” strategy unveiled in 2015 laid out specific five and 10-year targets for domestic firms on drugs innovation, export market development and import substitution.

Being able to produce better drugs domestically is key to China’s ability to lower costs and improve accessibility of medicines – especially for life-threatening cancers – and help shore up social cohesion amid the widening wealth gap between urban and rural people.

The popularity of the tear-jerking film Dying to Survive in July – based on the real-life story of a Chinese leukaemia patient who smuggled cheap but unproven cancer medicine from India for some 1,000 Chinese cancer patients – saw Premier Li Keqiang renew his call on officials to speed up price cuts for cancer treatment.

The elimination of tariffs and drastic cuts to value-added tax on imported cancer drugs in May and June this year reduced drug costs in the short term, but greater self-sufficiency and intellectual property ownership are the longer term answers.

Some domestic firms have already achieved partial breakthroughs on innovative drugs development for cancers that have received endorsement from their industry peers overseas.

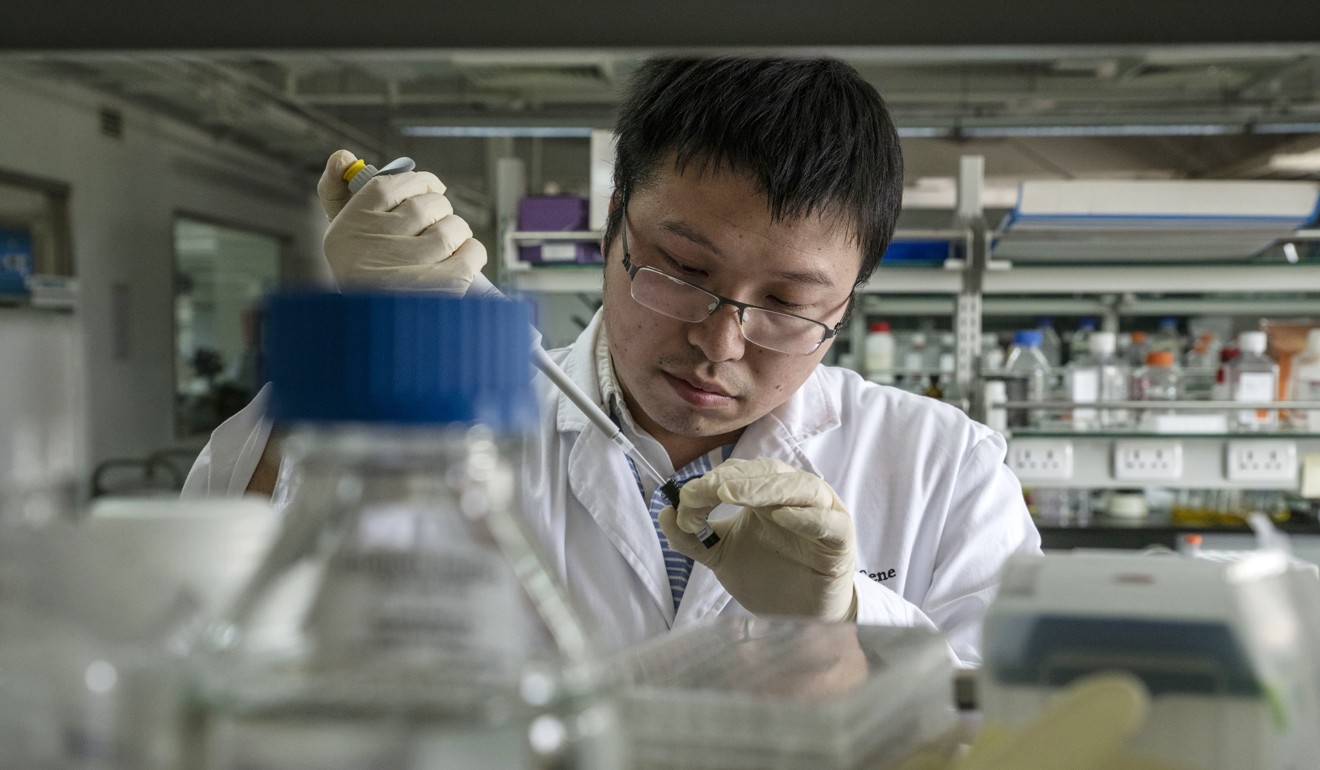

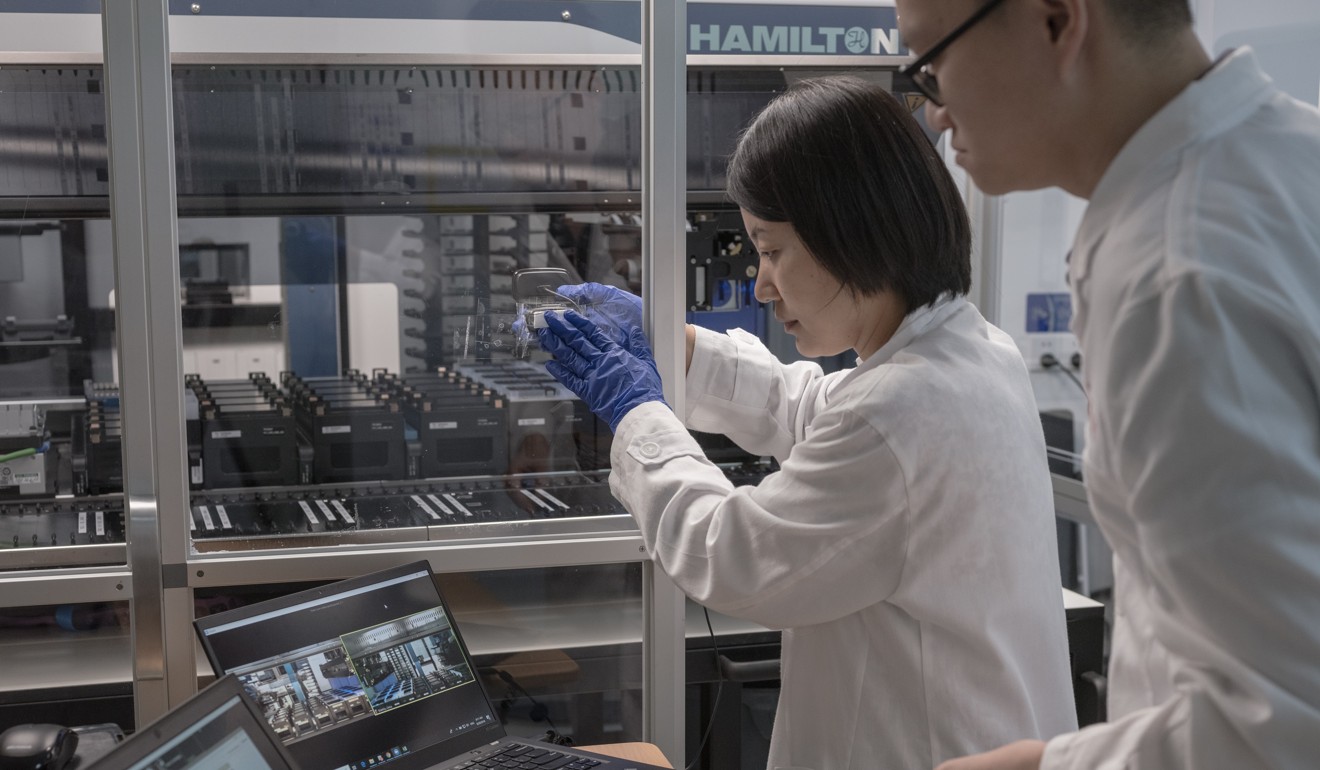

When Nanjing-based Genscript Biotech announced in December that US health care giant Johnson & Johnson’s offshoot Janssen Biotech had agreed to pay Genscript US$350 million upfront to co-develop a blood cancer treatment, it generated a buzz in Hong Kong’s stock market.

The investment deal saw Genscript’s share price jump 31 per cent on the day of the announcement, before surging almost 60 per cent in the next five weeks.

Janssen sent 90 people to Nanjing to examine Genscript’s data in a five-month due diligence exercise before proceeding with the investment in its experimental chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) technology, currently undergoing clinical trials.

China’s latest box office smash highlights plight of cancer patients forced to go underground to buy life-saving drugs from India

Genscript’s innovation last year cured American Craig Chase’s life-threatening multiple myeloma disease, a type of cancer, after six weeks of treatment in a Nanjing hospital, according to provincial news portal Jschina.com.cn.

Chase volunteered to become the first foreign patient to try the experimental treatment in a Chinese institution after three years of conventional methods in the US had failed. He was the sixth patient to be successfully treated with CAR-T therapy in the hospital, the report said.

AMBITIOUS LATECOMER

This success has not changed the fact that China is a latecomer in drug innovation.

Two of only a handful of drugs to make it past the industry watchdog in decades were Shenzhen ChipScreen Biosciences’ treatment for relapsed T-cell lymphoma in 2014, and Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine’s breast cancer novel treatment in August this year.

Last month another approval was announced, by Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing’s Hutchison China MediTech, which has ploughed US$590 million since 2000 into its mainland drug research projects, together with partners including international giants Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca.

The London and New York-listed firm’s capsules won unconditional approval to help extend the lives of colorectal cancer patients, who have failed at least two prior therapies and have an average life expectancy of six months, by an average 3.7 months. It aims to get three of its 11 cancer drug candidates to the market within three years.

China MediTech chief executive Christian Hogg said the sheer size of China’s patient pool – with a third of the world’s cases of colorectal cancer, half for gastric cancer and 40 per cent for lung cancer – is key to its potential as a future power in biopharmaceutical industry development.

“Cancer is extremely clever, it mutates very quickly,” Hogg said. “You try to shut off one switch [to stop cancer cells growth], but they will find another pathway to multiply.

“The future of oncology drugs development is all about combinations of targeted therapies, including those that shut down the blood flow to cancer cells, and immunotherapies which activate the immune system to attack the cancer cells.”

The challenge for drug developers was finding the “really clean” treatments that had the fewest unwanted side effects, he said.

Fierce competition in China’s nascent immuno-therapy cancer drugs market could compromise safety, say analysts

Beijing is keen for its nascent biotechnology industry to take on such challenges, and has not been coy about its ambition.

As part of the “Made in China 2025” national strategy, Beijing wants the Chinese industry to develop 10 to 20 innovative drugs by 2020 and commercialise 20 to 30 by 2025.

It also wants to see at least 100 pharmaceutical firms gaining US, EU, Japanese and World Health Organisation certification.

By 2020, Beijing wants registration completed for five new biological drugs so they can be marketed in developed nations, rising to 10 by 2025.

Other objectives include breakthroughs in 10 to 15 “major core technologies” by 2020, and the ability to produce generic versions of 90 per cent of blockbuster drugs after their international patents expire.

FROM COPYING TO CREATING

To accelerate the industry’s transformation from almost exclusively generic drugs manufacturing to an increasingly innovation-driven model, and to address the huge unmet demand for better drugs, Beijing has announced an unprecedented scale of reforms in the past three years.

They include measures to greatly accelerate new drug approvals through more regulatory manpower and streamlined procedures.

To close the incentive gap with Western nations for drug innovation, Beijing announced in April this year that it would grant patent extensions of up to five years on innovative drugs seeking marketing approval, both in China and abroad.

Chinese doctor’s near-miracle recovery after cancer immunotherapy shows the promise new treatment holds

Patents usually afford owners 20 years of sales exclusivity protection from the filing date and an extension provides key additional incentives, according to Hogan Lovells’ patent and trademark lawyer Andrew Cobden.

That was because the latter part of the exclusivity period was usually when manufacturers made the greater share of their revenue in the drug commercialisation process as their products gained recognition and market share, he said.

Another policy to encourage innovation was the establishment, almost four years ago, of specialised intellectual property courts.

These had enabled more intellectual property (IP) owners to get redress, Cobden said, adding that IP owners were reportedly successful in about 80 per cent of infringement cases decided by the Beijing IP court in its first 2½ years.

Previously, Chinese court decisions tended to favour local defendants compared to other nations, particularly in cases involving foreign IP owner plaintiffs, he said.

China’s pharmaceutical firms have spent a combined US$7.2 billion on research and development in 2016, according to a report by Washington-based non-profit public policy organisation the Brookings Institution.

While modest compared to the US$156 billion spent globally by pharmaceutical firms and the US$93.6 billion outlay of the world’s top 20 drug developers – mostly based in Western nations – China’s spending has jumped 44-fold from US$163 million in 2000.

“There has been a dramatic growth in Chinese R&D – now close to EU levels – indicative of Chinese efforts to become an innovation nation and position itself as a potential first mover in the biotech and green energy fields,” said a report on US technology development strategy by Washington-based international affairs think tank the Atlantic Council.

“The world is now much more competitive, and the United States and European countries risk losing their edge, which has negative national security implications.”

CATCHING UP WITH THE WEST

Western nations’ concern that China may one day catch up or surpass them in biotechnology development is not unfounded.

The global market share of mainland Chinese biotechnology and pharmaceutical patent applications has grown just over three times, to 32 per cent, in the decade to 2016, even though the share of patents granted rose to only 18 per cent from 10 per cent, according to data from World Intellectual Property Organisation and calculations by the South China Morning Post.

In the same time frame and in the same sectors, the US share of patent applications fell from 35 per cent to 28 per cent. US share for patents granted slid only marginally, from 32 per cent to 30 per cent.

China has also made great strides in developing some of the world’s cutting edge cancer treatments, one of a small number of pharmaceutical research areas in which it appears to be neck-and-neck with the developed world.

Of the just over 400 CAR-T clinical trials being conducted globally in late March, 166 were in China, one more than the 165 in the US, according to a Guosen Securities report that cited data from Clinicaltrials.gov.

Tu Youyou’s Nobel Prize for her anti-malaria drug inspires China’s pharmaceutical firms to innovate and improve

China’s advancement in the area is remarkable, considering the country had just 24 CAR-T clinical trials under way in February 2016, exactly half the number taking place in the US at that time.

THE GAP THAT REMAINS

But it is still too early to say who has the upper hand, as it is the quality of, and results from, clinical trials that count.

“Quantity doesn’t necessarily mean quality, the rapid emergence of a large number of players in a way indicates the industry is still emerging … many aspects of the ecosystem are still being established,” Wu of Quan Capital said.

One such aspect is the number of high quality clinical trial sites that can meet the needs of drug developers. There were just over 50 in China, compared to hundreds in the US, Hogg said.

China to speed up approvals for new drugs and plans to accept foreign trial data

Chen Li, chief executive of diabetes drugs developer Hua Medicine and a former China chief scientific officer of Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche, said that while China’s basic medicine research capability had been improving, its scientists had been publishing in leading journals, mostly about non-human research.

There had been only a limited, albeit increasing, number of research papers on clinical trials for human diseases written in China, trailing far behind the West, he said.

Helen Chen, head of LEK Consulting’s China biopharmaceuticals and life sciences practice, agreed there was still much catching up to do.

“As an emerging innovative industry, the achievements in terms of actual output is still limited [even as] China has been rapidly ramping up the number of IP filings and the amount of money spent on R&D,” she said.