Exhausted parents call for jobs for China’s autistic adults: ‘When I die, who will look after him?’

The lack of employment opportunities is a major reason most autistic adults stay home, triggering a cry for government help from worn-out parents

In the Chinese metropolis of Shanghai, 18-year-old baker Lu Xiuqi is a pioneer.

For five or six days a week, depending on his roster, Lu takes a bus and then subway to work at a supermarket bakery on his own.

What might seem like a mundane commute is a huge step in a long life journey for Lu, who was diagnosed with autism as a toddler. And his mother, Chen Jie, could not be happier.

“It’s a return for my years of efforts in training him [to manage his symptoms],” Chen said.

“I am proud of my son.”

Lu is one of an estimated 230,000 people aged over 14 in Shanghai with autism but one of the very few with a full-time paid job.

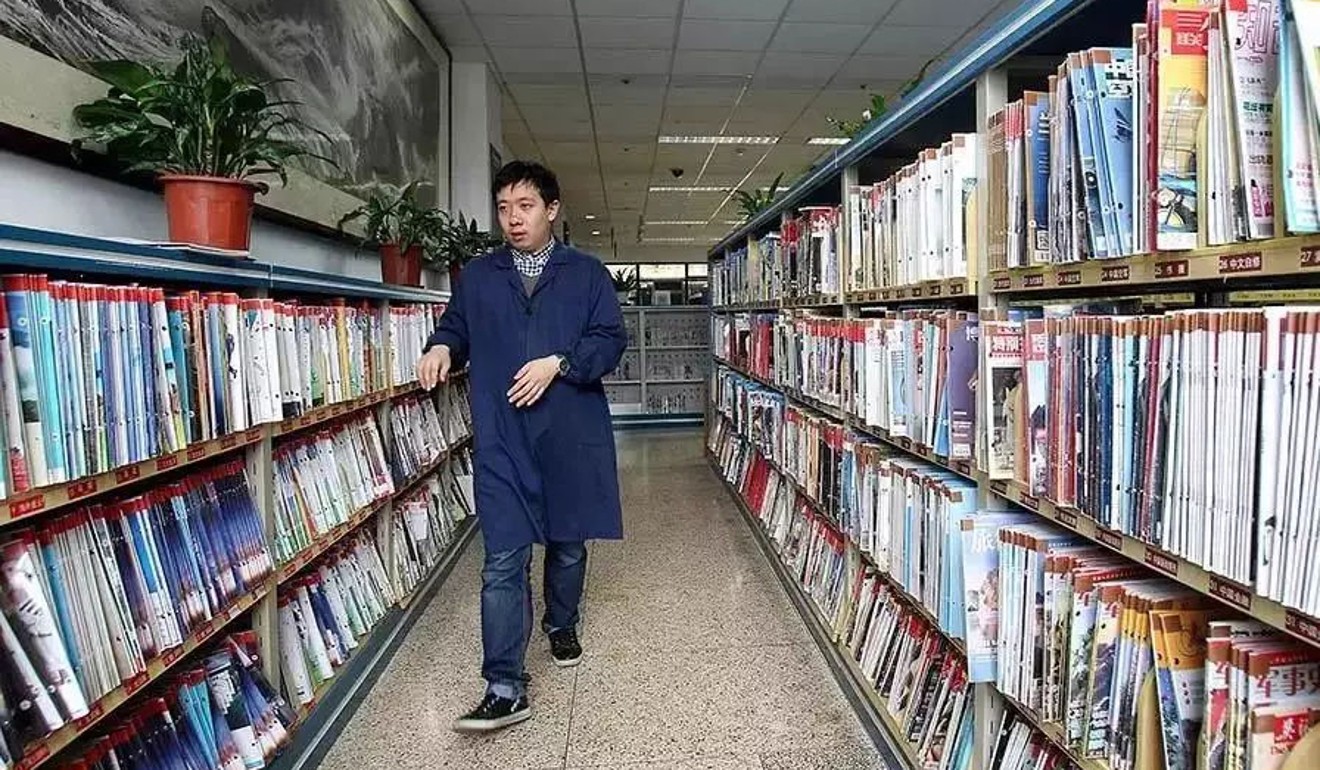

Last year, the city had just one: Gu Jiandong, a book sorter at Shanghai Library, Jiefang Daily reported.

A Hong Kong mother’s struggle to find the right therapist for her autistic son

Chen said that besides Gu and her son, she knew of no one else with autism in Shanghai who was formally employed.

That is why Chen and parents of some of the 10 million people around the country with the condition are calling on governments at all levels to provide facilities – from workplaces to day care centres – to support autistic adults.

“Otherwise, their parents have to stay at home to look after them all the time and can’t do other things,” Chen said. “What’s more, always staying at home is not [a good way] for autistic people to develop their social skills.”

Autism is a disorder that affects how a person behaves and interacts with others, their communication and learning, and it ranges in its severity and symptoms. Specialists are uncertain about its causes but they do know that it is more commonly found in males than females.

When Lu was diagnosed at age two, Chen opened a small learning centre and spent countless hours teaching him and other autistic children to deal with their condition.

How a Chinese mother went back to school to help her autistic son get into university

It was a struggle. She had to repeatedly guide her son on how to follow rules so he could navigate his way through the world around him.

“For the first few years, it was hard [to train him],” Chen said. “I often felt desperate and frustrated, since no matter which method I used to teach him, he couldn’t grasp it.”

Chen’s commitment and her son’s efforts eventually paid off when Lu was accepted by and completed a two-year vocational programme in baking and cooking. The course gave him the skills he needed to get the bakery job.

“My son is very lucky,” she said. “He is in a better position than most of his autistic peers.

“Almost all other [autistic] kids his age or above stay at home, with some helping their mothers making handicrafts and selling their products on the internet.”

Employment rates for autistic adults are low in many countries but in China, the rate ranges from extremely low to zero, according to a report released last year by the Beijing-based Wucailu Children’s Behaviour Correction Centre and Beijing Normal University.

Most people with autism who complete nine years of compulsory education do not go on to further education in China. A small number attend vocational schools for students with special needs, but still struggle to find a job after graduation.

How Google Glass can improve autistic children’s social skills by reading facial expressions

Conditions are a little better in the United States.

A report released last year by the AJ Drexel Autism Institute – a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania autism research organisation affiliated with Drexel University, a private research school – showed that just 14 per cent of people with autism held a paying job in the community. Over half, or 54 per cent, took part in an unpaid activity in a facility where most of their colleagues had disabilities, according to the report.

And in Britain, the National Autistic Society said in a report this year that only 16 per cent of autistic adults had full-time paid employment, a level unchanged for more than a decade.

Lu Xiaotong, an early childhood education and nursing specialist from Teikyo University of Science in Japan, said it was essential for autistic adults to go out to work and be included in society.

Work forms can vary, depending on how severe their disorders are,” Lu said.

“The amount of how much they are paid is not important, but that they have some place to go to, instead of staying at home all day.”

Helen McCabe, co-founder and executive director of The Five Project for International Autism and Disability Support in the US, agreed, saying that when people with autism received some job support, they could be successful employees.

Such support can consist of providing “more understanding and support, like direct instruction or direct advice on how to interact and how to communicate with your colleagues,” McCabe said.

China’s autistic children and a pioneering woman’s model for rehabilitation

Gu Jiandong, the Shanghai Library book sorter, has experienced this need first hand.

Gu’s mother, who would only be identified by her surname Zhang, said that before her son, now 26, got his job in 2012, prospective employers “said hiring him would be a big risk”.

She said the library wanted to know if it would be expected to pay compensation if Gu was hurt at work. “We said we won’t ask for any compensation from the library,” Zhang said.

Zhang said the government could provide insurance to make it easier for enterprises to take on autistic employees. “If the government solves this problem, like buying insurance for enterprises, the enterprises don’t have such concerns,” she said. “It’s more likely for autistic people to have jobs then.”

Once Gu started work, Zhang’s husband took on a role as her son’s job coach. For two months the husband “spent one hour per day at the library, teaching our son how to work and teaching his colleagues how to communicate with him”, Zhang said. “At first, his colleagues were afraid of my son. They didn’t know whether they should talk to him or not.”

Although Gu soon showed he could handle the work, he chatted very little with his colleagues, his mother said.

“I was told that when he was not busy, he just sat in a corner by himself, or walked up and down. Sometimes he smiled for no reason,” Zhang said.

‘They just want to hear them say mum or dad’: parents of Hong Kong’s autistic children struggle to get the support they need

Cao Xiaoxia, founder of Shanghai Angels Salon, a charity that helps autistic children through music education, said education at an early age was key to helping people with the disorder find a job.

Cao said that most autistic Chinese adults in their 20s or older were incapable of working independently owing to not having been trained to manage their disorder when they were young.

“Now that these [autistic] people are older, it’s hard to [get them to] study new things to alter their behaviour,” she said.

But Cao’s organisation and others such as the Blue Harbour Youth Development Centre, a Shanghai-based NGO offering free vocational courses for autistic teenagers, are hoping to make a change.

Blue Harbour starts where the nine-year compulsory education system ends. The organisation was launched four years ago in response to parents’ demand for learning opportunities for their children.

“We teach them to make lipsticks, cakes, red envelopes and jewellery. We also teach them to cook and use sewing machines,” co-founder Chen Lingping said.

The pace of learning is mixed, with some of the 70-plus autistic students learning quicker than others. A challenge for some students was simply learning to obey rules, Chen Lingping said.

“For people without autism, it’s an easy and normal thing,” she said. “But for autistic students, it takes them a lot of time to learn.”

For Chen Jie and other parents the concerns for their children do not stop there.

“When we die, what can my son do? Who will look after him?” she said. “Even if we leave some money for him, he doesn’t know how to use it.”

Lu’s condition is complex and his future is uncertain. But at least for now, Chen Jie is greatly relieved, knowing her autistic son is able to go to work independently.