Chinese clients of New York ‘asylum mill’ lawyers face deportation threat

Fear and confusion as US cracks down on thousands who may have heeded advice to exaggerate or fabricate their asylum claims

A crackdown by US immigration authorities on thousands of potentially fraudulent asylum applications is reverberating throughout the Chinese immigrant community in New York, causing anxiety and confusion as applicants rush to find legal strategies to avoid possible deportation.

The US is reviewing more than 13,000 cases handled by immigration lawyers, agents and others convicted after a 2012 investigation called Operation Fiction Writer. Those who were found guilty helped more than 3,500 immigrants, mostly Chinese, win asylum status, US authorities said.

The current inquiry was first reported by National Public Radio’s Planet Money on September 28.

The 2012 investigation involved about 3,500 asylum grants, and the number of “derivative applications” submitted by family members now exceeds 10,000, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) told the South China Morning Post.

The agency said that some 13,500 Chinese immigrants who were granted asylum before December 2012 could lose their status and potentially face deportation. Immigration judges have the authority to terminate grants of asylum, ICE said.

The reviews – which are being conducted by the US Departments of Justice and Homeland Security – began in 2014 during the Obama administration, according to the agency.

It can be a challenge for immigrants to meet the US asylum criteria, but for those who are eligible, asylum is a faster and easier route to permanent residency and eventually citizenship compared with other, more restrictive immigration programs. An applicant can obtain a work permit soon after an asylum application is submitted. Once asylum status is granted, recipients may file for green cards and bring family members to the US.

During the 2012 fraud investigation, immigration officials determined that thousands of Chinese asylum applications contained fictitious details of persecution and had been prepared by a small number of law firms caught up in the sweep.

Chen Yonghui – an immigration lawyer in Flushing, Queens, a New York City neighborhood with a large Chinese immigrant population – has taken on more than 10 cases since the Planet Money report was broadcast. Chen’s new clients all obtained asylum with the help of people convicted in Operation Fiction Writer.

“The news has blown up in the Chinese community in the past five days,” Chen told the Post.

The new crackdown is having a profound impact on Chinese immigrants, said Muzaffar Chishti, director of the Migration Policy Institute's New York office. The MPI is an independent, non-profit think tank in Washington dedicated to immigration analysis.

“It's messy. It's anxiety-creating. It’s upending the lives of people who have lived here for a very long time,” Chishti said.

Lawyers, immigration scholars and people involved with the Chinese immigrant community said it was unclear how many of the cases filed by the convicted lawyers were fake, but said the sweeping investigation could also upend the lives of innocent people who obtained asylum legitimately.

The revisiting of cases “will have a discriminatory impact upon the Chinese who have filed record numbers of successful asylum cases but who will bear the brunt of those who filed fraudulent asylum claims,” said Stanley Mark, senior staff lawyer at the Asian American Legal Defence and Education Fund.

During the Obama years, it was primarily lawyers, agents and those who made fraudulent claims on behalf of their clients who were prosecuted, Chishti said. But the Trump administration has stepped up the targeting of clients who won legal status through the use of so-called asylum mills.

Chen said that last year, he successfully defended a client who was facing deportation because she was granted asylum through John Wang, an immigration lawyer in Manhattan’s Chinatown who was convicted in the Operation Fiction Writer round-up.

After being granted asylum, Chen’s client applied for permanent residency in 2013, and received no updates until 2016. She then got a notice from US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) that she had been placed in deportation proceedings and that the government was seeking to rescind her asylum status, Chen said. The government said it believed it had been fraudulently obtained because of who represented her.

“You can’t rely on the unethical attorney representing a petitioner as a reason to terminate a bona fide asylum case,” Chen said of his defence. “The government has a burden to prove the case was fabricated.”

On her application, Chen’s client said she had been persecuted by the Chinese government because of her religious beliefs. Chen declined to comment on the validity of the claim.

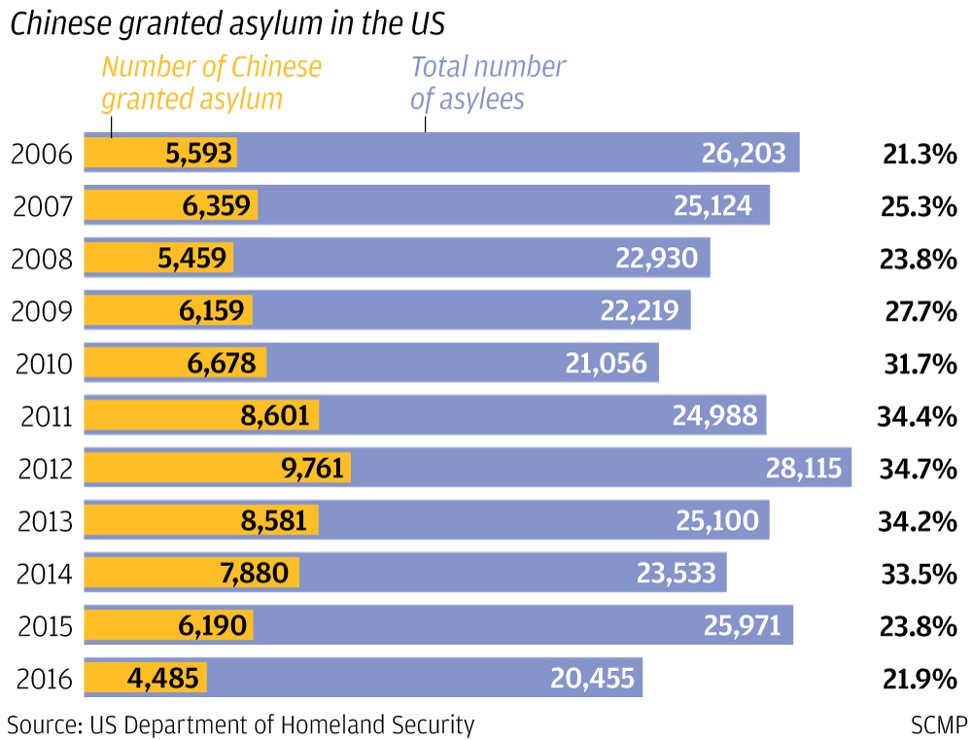

Immigrants from mainland China have long been the top group of US asylum recipients in terms of numbers, according to the Department of Homeland Security. And that trend has continued even after the Operation Fiction Writer sweep.

Chishti said that historically, the Chinese have been more successful than other nationalities partly because American asylum law uses criteria based on race, religion, national origin, political opinions and social groupings.

“There were inherent factors in the Chinese asylum cases that made them sort of fit the narrative that the government wanted to hear,” Chishti said.

Such factors include pressure to terminate pregnancies under Beijing’s recently abandoned one-child policy, religious persecution and prosecution for fighting for democracy under a Communist regime.

Although authorities are investigating cases handled by lawyers convicted after Operation Fiction Writer, other law firms could be implicated, Chishti said. He anticipates that the federal government will turn many affected immigrants into cooperating witnesses, which could entitle them to apply for a U visa, a type of nonimmigrant visa for victims of certain crimes, as a form of relief.

Teng Biao, a Chinese human rights lawyer who is a visiting scholar at the New York University School of Law, said future asylum seekers could also be affected.

“Immigration policies under Trump have tightened, and if fake applications from a particular country are found to be particularly common, I’m afraid the procedure for future applicants might be more tedious and the bar could be higher,” he said.

Teng, who testified at an asylum review hearing in March, said the similarity of the stories told by Chinese asylum seekers and the “almost identical language” in them has created suspicion.

“Some of them returned to China, some more than once, in the middle of their asylum application,” he said. “I think that showed they were not persecuted in China.”

Although some asylum seekers were coached by unethical lawyers, Chishti said, they were not entirely innocent because they had lied on their applications. But Chishti emphasised that the immigrants were far more vulnerable than those in the legal profession who facilitated their cases. For the immigrants, prosecution could mean not only a jail term but deportation. The lawyers, who most likely are US citizens, would not face that threat.

Jennifer, a 34-year-old businesswoman in Iowa who asked that her full name not be used, was granted asylum about five years ago in California. Someone at the Chinese family hotel where she was staying in Los Angeles had directed her to an agent, she said, who guaranteed her a green card for less than US$3,000.

“Instead of taking a risk, seeking asylum rather feels like counting on luck,” Jennifer said.

Because of restrictive immigration policies and prolonged waiting periods, Jennifer said that 80 per cent of her friends in situations similar to hers – neither rich nor skilled – sought asylum to be able to stay in the US.

“People aren’t really proud of what they did,” Jennifer said. “On the one hand, you are defaming China, and on the other, you are sort of lying to America. It’s not an ideal solution.”

Jennifer was granted asylum on the basis of religious persecution. She identified herself as a Christian but said she was “not so devoted”. The case writer from her lawyer’s office embellished Jennifer’s story with details about persecution by Chinese authorities, which she had to memorise and rehearse before the asylum interview.

“Not all of the claim was fake,” she said. “Part of it was true. It was just exaggerated.”

Immigration experts acknowledge that a certain percentage of asylum applications are fabricated, but say it’s unfair to generalise that the practice is rampant within the Chinese immigrant community. They say what’s more obvious and troubling is that the system is ripe for abuse by unscrupulous lawyers and others who prey on lower-income immigrants who are not proficient in English and lack an understanding of the US immigration system.

“I can’t tell you how many times that has happened to my clients, where they innocently thought they were applying for a work permit, and then they later come to find out that the attorney had basically made up the story about them being persecuted and had actually filed an asylum instead of a work permit application,” said New York-based immigration lawyer Tsui Yee.

Yee is now representing a Chinese client facing deportation after using a lawyer convicted in Operation Fiction Writer. The hearing for the client, who claimed religious persecution, has been set for January 2020.

For many Chinese asylum seekers, they were simply convinced by their countrymen that asylum was an affordable and fast way to a better life in the United States, so they went along with the fabricated cases without considering the possible severe legal consequences.

“If the government wants to rake up the past in order to kick people out, I could well be that person who can help them jack up the number,” Jennifer said. “There’s nothing I can do about it.”