‘Dying to Survive’ gets real: China cuts price of life-saving cancer drugs

Costs slashed by over half on average, in wake of hit movie featuring the plight of those unable to afford prohibitively priced medicines and forced to look abroad

China has included 17 life-saving cancer drugs in its national public insurance after negotiations drastically cut their prices, in response to their cost fuelling the smuggling of cheap drugs from abroad in an echo of the popular Chinese film Dying to Survive.

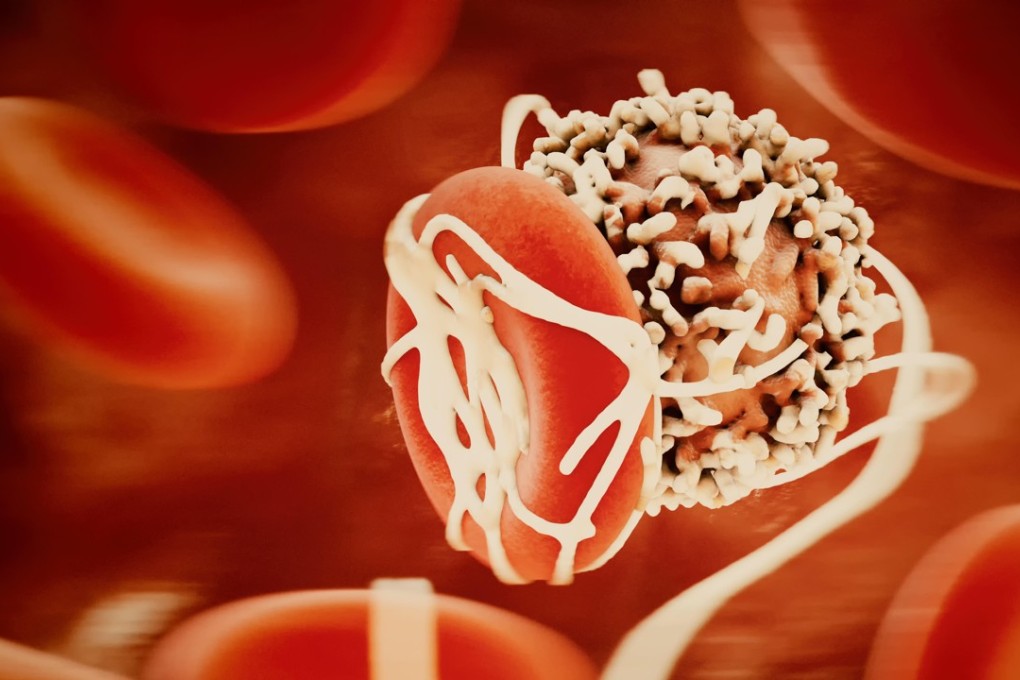

All of the drugs – 12 for treating solid tumours and the others for blood tumours – are considered clinically necessary, effective and urgently needed for patients suffering from non-small-cell lung carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, melanoma, lymphoma and other types of cancer, according to a statement by the State Medical Security Administration.

Most of the drugs are produced by international pharmaceutical giants such as Novartis, Pfizer and Merck and are far from patent expiration. The prices have been brought down 56.7 per cent on average, with imported drugs 36 per cent lower than in neighbouring markets, the administration said.

“We have more power in price negotiations and achieve the target of more quantity for lower price,” Hu Jingling, head of the administration, said in an interview with China Central Television.

The administration was set up in March and oversees insurance for both rural and urban residents, instead of two agencies previously.