So many Indians and Pakistanis, why so few Chinese in British politics?

- Despite their educational and economic success, ethnically Chinese people are still underrepresented in the British parliament

- Nicolas Groffman examines the reasons why this may be the case

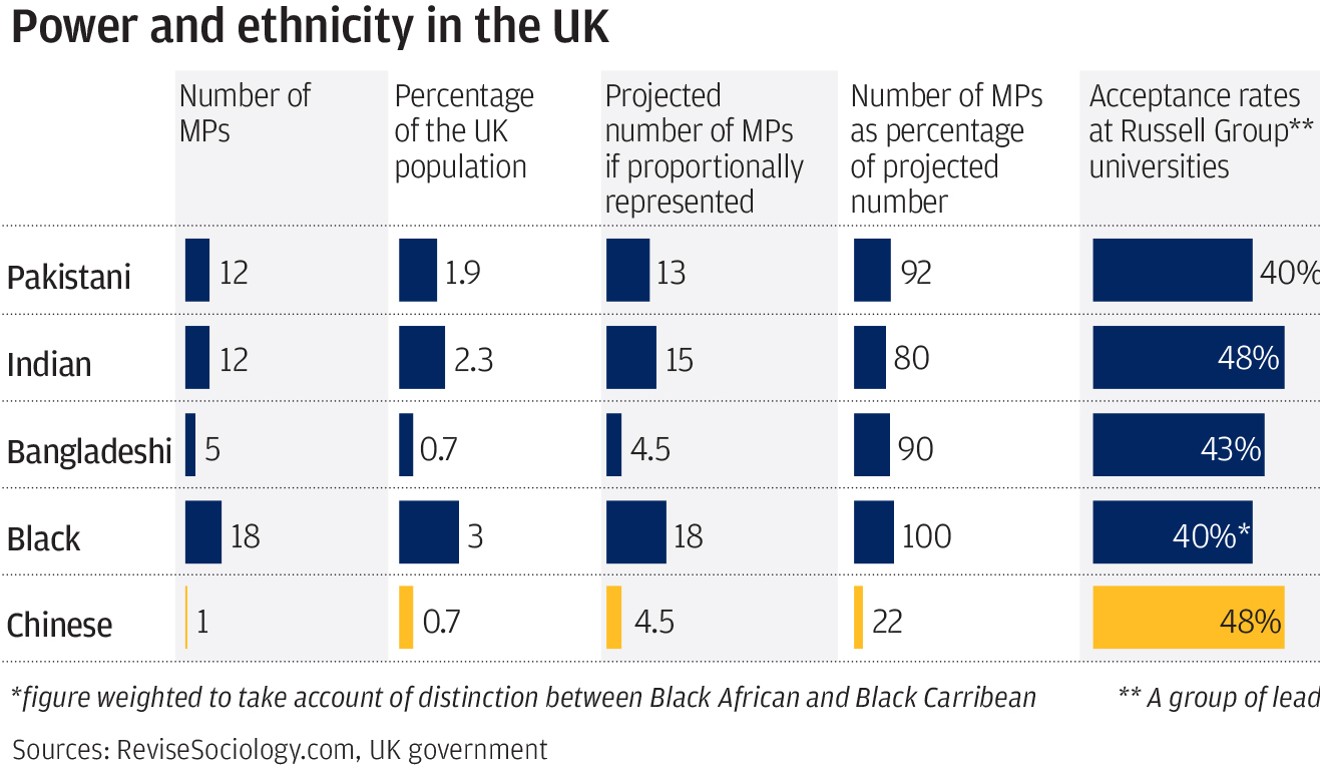

The Chinese are greatly under-represented in British politics. According to the last census, there are 433,150 ethnic Chinese in Britain, 0.7 per cent of the population, around 40 per cent of whom were born in mainland China.

If they were proportionately represented in parliament, one would expect four or five MPs of Chinese ethnicity.

If we take representation in the House of Commons as a guideline, all other ethnic groups do better in politics than the Chinese. There are, for example, 29 MPs of South Asian origin.

As the chart above shows, the Chinese community in Britain is financially and academically a net contributor to society and scores above average compared with other ethnic minority groups, but it is the weakest link in politics.

Incidentally, the Chinese are also under-represented in the performing arts, the military and the police.

What is it about Chinese ethnicity that brings about this disparity? It is clearly not educational attainment or wealth, which are both above average for Chinese Britons.

The Chinese are good tax payers, and get involved in community activities as volunteers and workers. But it does appear that cultural and behavioural factors are restricting them from standing for election. Is it because they are selfish? Timid? Uninterested in politics?

Liberal Democrat peer Clement Jones, deputy chair of the all-party parliamentary group on China, puts it differently: “The Chinese in Britain tend to take a Confucian approach to politics, preferring gradual change to firebrand oratory.”

The fact is that when Chinese people do make an effort, they tend to do reasonably well even if they do not get voted in.

Back in 2010, a mainland Chinese-born candidate stood as a Conservative in Liverpool Riverside and got a respectable 10.9 per cent of the vote.

This was despite having a strong Chinese accent and standing in a constituency that traditionally votes Labour by a huge majority.

The candidate, Wu Kegang, actually increased the Tory share of the vote by 2 per cent.

Now chairman of the BCC Link to China, an organisation dedicated to building partnerships, he looks back on that election as a significant learning experience.

“I would never suggest the system is rigged against Chinese candidates,” he told me recently.

“No one attacked me because of my race. In politics, it’s not a question of whether the system is fair or unfair.

“It’s about whether you can connect with your electorate. You can do that any way you like.”

Alan Mak, who was born and brought up in England, is not eager to talk about ethnicity.

He wants to be – and generally he is – liked or disliked on the basis of his politics and his manner rather than his Chineseness.

Mak has observed growing numbers getting involved in grass-roots politics and community campaigns, and says he hopes this will translate into more elected Chinese representatives in the future.

In his own constituency of Havant, on the south coast of England, the population is 98.5 per cent white. There is nothing Chinese about Mak’s campaign or his politics.

The story could not be more different for Yang Jian, an MP in New Zealand who has a whole website in Chinese complete with WeChat accounts and teams of Chinese volunteers working on his campaign.

For Chinese immigrants to the UK, Brexit is a faint beacon of hope

His political work was of course related to his constituency and its local issues, but the overtly mainland Chinese nature of some of his campaigning and the fact that he had worked in China within the intelligence services before he moved to New Zealand prompted accusations he had helped train spies before he moved to New Zealand.

Yang’s story is savoured by some of Britain’s intelligence wonks, who think it is an example of cunning Chinese infiltration into free-world politics.

It isn’t – it’s an example of how wafer thin Chinese political influence really is.

Even intelligence insiders like Yang can shrug off mainland Chinese doctrine with little effort after a few years in the Anglosphere.

Some point to the traditional unwillingness of Chinese people to stick their heads above the parapet. “A gun shoots at the leading bird” is an old Chinese saying on the dangers of standing out.

Yet it would be beneficial for the UK as a whole if more Chinese were involved in its politics.

Chinese people bring their traditional virtues of diligence and intelligence, and in a well-administered society, they can develop these virtues for their own benefit of and for society. ”

In the case of immigrants turned citizens, they bring a strong objectivity. Second-generation Britons of any ethnicity tend to be carried along with mainstream opinion, but first-generation immigrants are more resistant to local groupthink.

This was particularly evident in the Chinese immigrant response to Brexit, which has been phlegmatic and, indeed, optimistic.

There has been a marked improvement in Chinese participation in other forms of politics. For example, many universities have had Chinese leaders in their student unions, and many town councils have Chinese members.

University of Birmingham opens door to students with top grades in Chinese gaokao entrance exam

These are feeble beginnings, and some of the student leaders are simply people who have been asked to put their names forward by the Chinese Students and Scholars Association in the belief that this will somehow forward China’s interests in Britain. But it is better than nothing.

It is perhaps unfair to be too demanding of the Chinese community while its numbers are small. The Indo-Pakistani-Bangladeshi population, if taken as one group, amounts to nearly 5 per cent of Britain’s population, so it is perhaps not surprising that it feels more at home and participates more in public life.

The answer, according to Wu Kegang, lies not with the electorate but with Chinese people themselves. You can’t force people to become public servants.

They need to make the effort to communicate outside their own circle of friends, and to care enough about local politics to use their skills and experiences to help the wider community.

When this happens, it will benefit not just British Chinese, but the wider UK.

Nicolas Groffman, who practised law in Beijing and Shanghai, is a partner at law firm Harrison Clark Rickerbys in London