How China’s Penis Monologues are trying to detoxify masculinity

- Male counterpart to The Vagina Monologues aims to challenge traditional Chinese gender stereotypes and tackle domestic violence

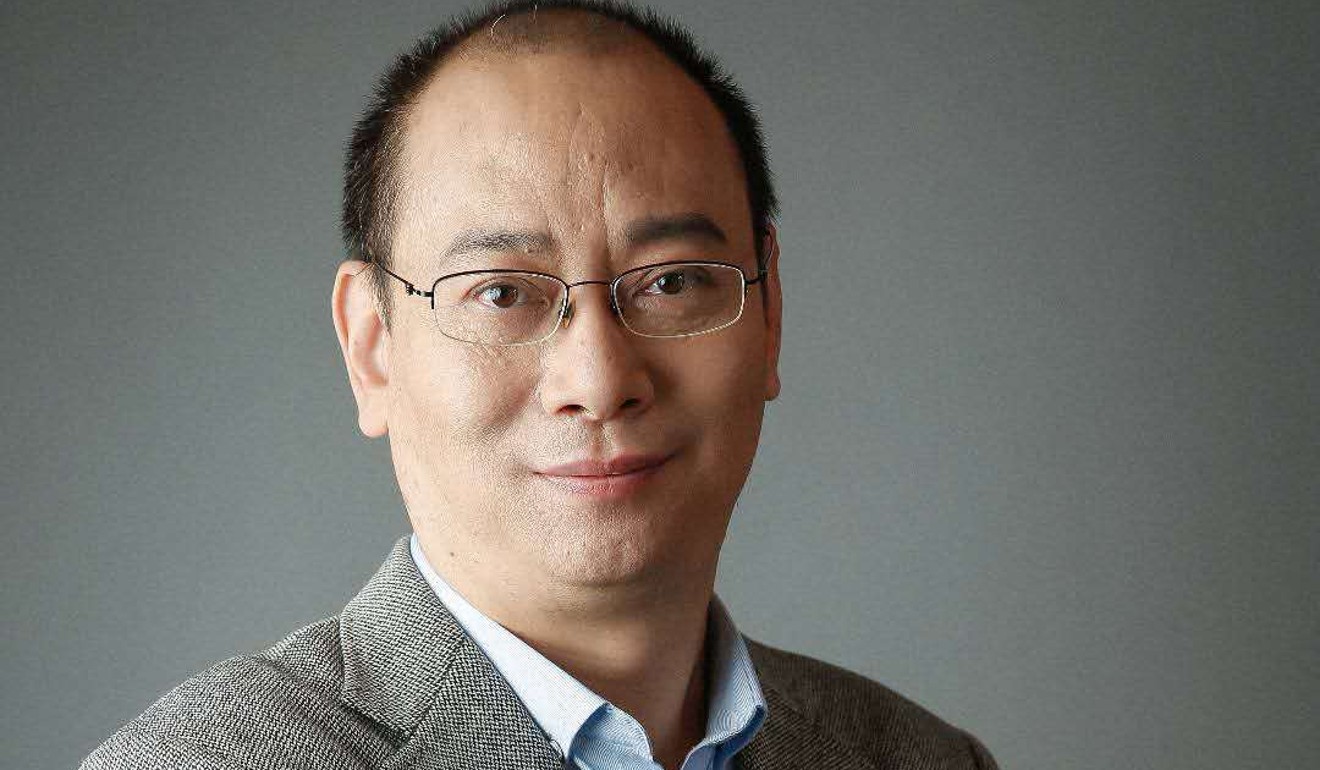

- Work was written by Fang Gang who founded a group that provides counselling for wife beaters in the hope of reforming their behaviour

“What's the symbol of man?” one man asked on stage.

“The penis!” nine men answered together.

“What do you call your penis?” the man asked again.

“Birdie.” “Tea kettle.” “My precious.” “Cock.” “The thing.” the other men answered one by one.

There was not a single sound in the audience. They held their breath, listening intently.

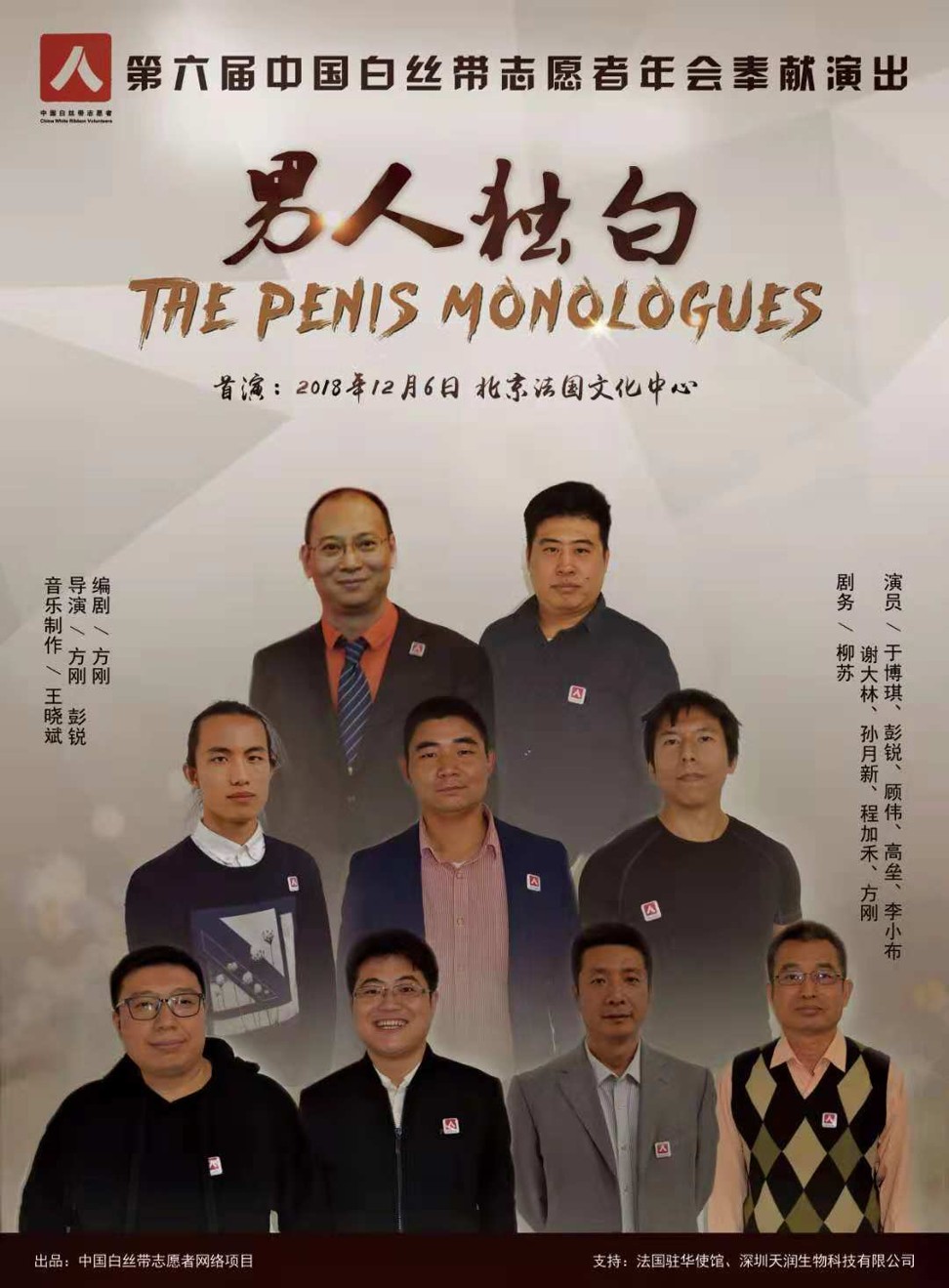

The scene took place at the French embassy in Beijing on Thursday, at the opening of The Penis Monologues, a play written by Fang Gang, a renowned sexologist and professor at Beijing Forestry University.

The play was presented during the annual meeting of China White Ribbon, a group Fang launched in 2013 to provide counselling to domestic abusers to stop the problem at its root.

For years, Fang has been working on changing men’s role in Chinese society as well as traditional views of masculinity.

He watched Eve Ensler’s play The Vagina Monologues more than 10 years ago and was blown away. Since then, he wanted to do a male version that tackled violence and discrimination by men towards women from the perspective of men and finally got around to doing it this year.

“I hope this play can prompt men to reflect and grow,” he said.

The scenes of the play are intended to challenge traditional Chinese views on masculinity and promote gender equality by tackling issues such as date rape, homophobia, impotence and domestic violence.

The monologues are mostly based on true stories that Fang has heard over years of research and interviews with men.

One by one, the actors present the solo scenes on stage. Then at the end of each story, there are a few lines of reflection.

I thought I loved her, but I didn't respect her choices

“When my penis entered her body, I was overcome with ecstasy. She is finally mine … it's like I put a stamp on her body, a label that marked my sovereignty.” one actor says, recounting the story of a date rape.

"[Years after] I realised that I had date raped her … when I was raping her, I satisfied my need for control, occupancy and conquest, not love. I thought I loved her, but I didn't respect her choices.”

One of the actors, Zhuchuan, told the real story of his own life on stage. He identifies himself as “queer”; he has loved wearing skirts from a young age but was bullied at school.

“My classmates used to call me a sissy, an idiot, a nut job,” he said.

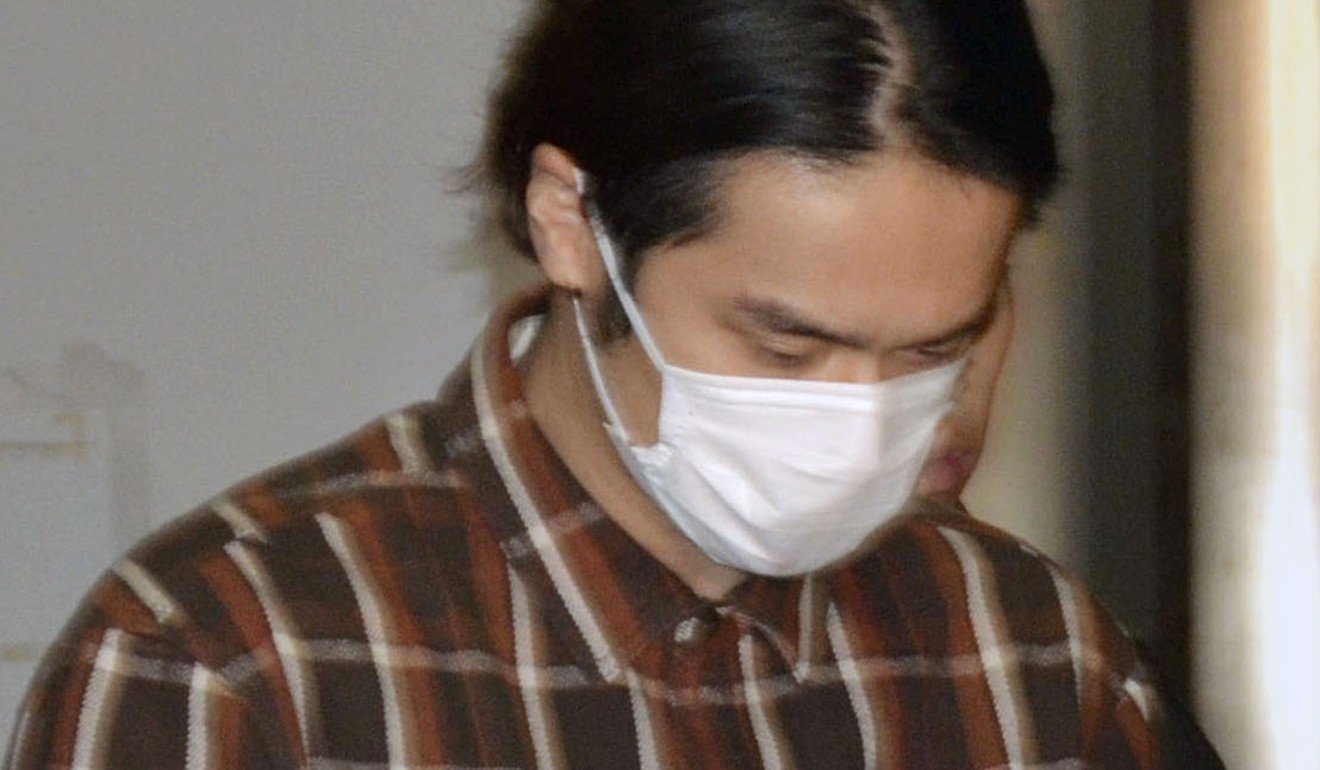

Chinese actor Jiang Jinfu ‘admits charges’ in Japan over Haruka Nakaura domestic abuse

“I never told my parents that I like to wear dresses, I could only wear them in secret, such as at dress-up parties.”

He had communicated with Fang extensively beforehand, so the playwright could produce a scrip based on Zhuchuan’s story.

In the play, he talks about how he came to question the so-called “male role”. He asks whether one needs to fit into that role as long as one has a penis, eventually concluding there does not have a be a single rule about gender.

“I hope more people, especially men, can rethink themselves as well as society's culture after watching the play,” he said.

Fang first started work in this field in the 1990s. Before becoming a sexologist, he worked as a journalist in the northern city of Tianjin and started interviewing gay men in Beijing.

At that time, homosexuality was regarded in China as a disease and the LGBT community remained hidden.

One of the main meeting places for gay men at the time were little-used public lavatories, so Feng contacted a group of men at one such place and arranged to go to dinner with 10 of them.

He recalls they talked about sex in an open manner – something that was largely taboo at the time.

Chinese mum fakes son’s kidnapping to test husband’s love

He said he felt discomfited and could only laugh awkwardly when one man picked up a chopstick and asked: “Mr Fang, is your cock as long as this?” – but in retrospect he found their openness liberating.

“It challenged the societal oppression people faced,” he said. “I had never thought you could talk about sex so freely and openly.”

He became close with the group and many others. In 1995, he published a series of books on sex, homosexuality and Aids in China. Soon after their publication he was fired by his employers.

Fang used this time to explore more into gender theories and sexology and became inspired by reading Western feminist theory.

Much of his and the White Ribbons' work have been dedicated to challenging traditional masculine stereotypes, with activities such as teaching men to do housework and learning how to care for their children, but the most import focus is on stopping domestic violence.

This year, during a marathon, the White Ribbons arranged for more than 10 volunteers to run in red high heels – an event inspired by the worldwide charity event ”Walk a Mile in Her Shoes”.

Falling sperm counts in China may hurt effort to boost birth rate

But changing men's roles and self-image in Chinese society is not easy – a problem illustrated by a slew of high-profile domestic violence cases.

In the most recent example the Chinese actor Jiang Jinfu admitted to beating up his Japanese girlfriend Haruka Nakaura and has since been charged by police in Tokyo.

Nakaura said that Jiang had hit her with a hammer and kicked her in the stomach, causing her to miscarry their child, but the reaction of most fans on Chinese social media was to excuse Jiang’s actions.

Some justified his behaviour by saying Nakaura had cheated on him, with others said he had showed his “manliness” by taking control of his woman.

The White Ribbons tries to tackle such attitudes one man at a time.

One of those who sought help from its hotline was Gu Wei, now 35, who contacted the group in 2014 after his wife filed for divorce as a result of his violent and abusive behaviour.

He was copying the example of his father and uncles, who also beat their wives, but he had started wondering whether his behaviour was wrong after his wife left him.

Eventually counsellors from the White Ribbons showed him how his actions had been shaped by societal and family traditions and how it was possible to change.

Gu, who learned how to take care of son by himself and carry out domestic duties, now volunteers for the helpline and has become a vocal critic of domestic violence and supporter of male participation in housework.

Chinese wedding day violence forces groom into car’s path

Fang hopes that his play will help promote this message and plans to stage it in other cities and put it online to help spread the word.

It ends with a clear message recited by all nine actors in unison: “The symbol of a man isn't the penis. The pride of a man isn't an erection. 'Man' shouldn't mean 'violence.

“A good man doesn't need to be macho and hegemonic, doesn't need to be sexually active. They can do housework, can take care of their children, can say no to violence and can respect diversity and promote gender equality.

“Only by making changes as a man, can I bring the kind of life I want.”

.jpg?itok=H5_PTCSf&v=1700020945)