After the Doolittle Raid: across the generations, second world war ties that bind China and the United States

- As a museum to the Doolittle Raiders opens, family members visit Chinese villages that rescued the airmen after the 1942 US attack on Tokyo

Weeks ago, in the cool of late October, Thomas Macia finally saw the mountainous land and village homes of Gangfeng county in Jiangxi province he had heard about all his life, territory his father would describe in stories from the second world war.

It was there James Macia, a B-25 navigator, had to bail out and parachute into the rainy night of April 18, 1942 – just hours after bombing Tokyo in the Doolittle Raid, the first-ever air attack on Japan’s home islands, and a turning point in the United States war in the Pacific.

James Macia and his four fellow airmen of Crew 14, including one who was injured, were eventually rescued by local villagers amid bombing by the Japanese army and travelled west until they reached Chongqing, then the capital of Nationalist China.

Thomas Macia, 71, had always been curious about the route his father took through China. He began to identify those locations after James died in 2009, at 93. During a three-day trip in late October, Macia saw the hill where his father landed and spent the night, and spoke with people whose parents or grandparents helped move him to safety.

“It was very gratifying to actually see the terrain and the locations and meet people whose ancestors had protected and assisted my father. Without them, I would not be here today,” said Macia in an email interview from the United States.

Before he left Jiangxi, he wrapped some stones in part of the parachute his father used 76 years ago, and brought them back to his home in Arlington, Virginia.

“I wanted to have a piece of China that represented the area where my father was in 1942. It serves as a tangible connection with the location in China of this very historic and important event in his life, and in the memory of my family,” Macia said.

Thomas Macia is a member of Children of Doolittle Raiders, a group of families of the men who took part in the Doolittle Raid. First the men themselves, and now their families, maintained ties with China over the years, even though the Chinese and US governments had their ups and downs in official relations. For the families, the relations formed through the blood and death of their fathers should continue to be nurtured.

The Doolittle Raid involved 80 airmen aboard 16 B-25s, and 75 crash-landed or had to bail out of their planes in Jiangxi, Anhui and Zhejiang provinces, including three who were killed in action and eight captured by the Japanese troops.

Chinese civilians and soldiers helped 64 of the raiders, using stretchers, jampans, doolees, trucks and trains to move the men through war zones to safety within a month.

US survivors of Doolittle air raid on Japan meet for one final reunion

Over the years, some of the raiders’ children have tried to retrace their steps in China, an act that not only commemorates their fathers’ heroism, but firms their bonds into another generation. Along the way, they lighted the hearts of many Chinese who may not have known the bravery of their own fathers as unsung rescuers.

Last month a museum dedicated to the Doolittle Raid opened in a scenic spot in Quzhou, Zhejiang province. Situated in an ancient courtyard with white walls and dark cornices, the museum featured photographic introductions to each raider and exhibited 200 items from the raid, including wreckage from some of the crashed planes.

Quzhou was home to one of three airstrips the raiders planned to land on, had the operation not started hours earlier and farther from Japan than scheduled because the US Navy had been spotted by Japanese picket boats. The Chinese side was not notified of the change in plans and the airfields, where the planes were supposed to land on April 19 to refuel, were not open the night of April 18.

Short of fuel and with no response from the airfields, the raiders had to bail out or crash-land, not knowing for sure whether the area was controlled by Chinese or Japanese troops. In all, 51 raiders ended up in Quzhou before they were smuggled out to safety.

A delegation of 24 Children of Doolittle Raiders members travelled from the US to take part in the museum’s opening ceremony. Also present was a local historian from Shangrao, who later would inform Thomas Macia about the people involved in his father’s rescue.

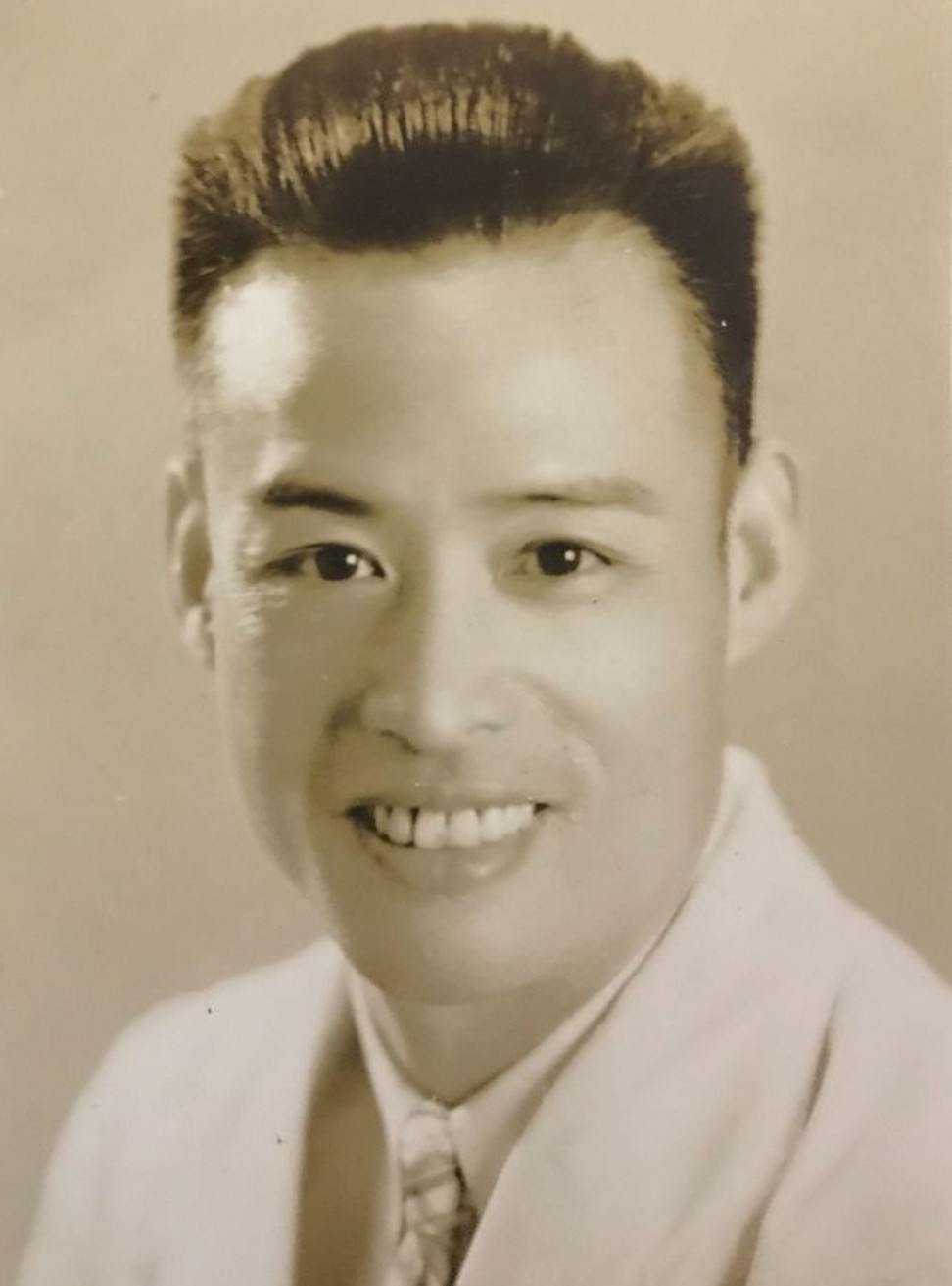

Luo Shiping, a history professor from Shangrao, Jiangxi province, saw the photo album Macia brought along and noticed a name card, which read Dr B C Chen and included an address in Shangrao.

Dr B C Chen was on the list James Macia provided to the US government of those who helped rescue him, but the identity of the man had always been unknown to the son.

With wide connections, Luo sent out a message in his circle and within hours he received word: the card belonged to Dr Chen Baocong, who had been a senior army doctor in the No 3 War Zone Hospital.

Trained in Tongji Medical School in Shanghai, Chen spoke fluent German and English. During the war, he worked as a translator in the hospital and helped treat injured pilots – four crews from Doolittle’s Raid parachuted into the Shangrao area and some had been injured, Luo said.

Last of Doolittle crew celebrates 102nd birthday

Chen was better known as one of the organisers of a student movement in Tianjin in 1925 and was thrown in the same prison cell with Zhou Enlai, later the first premier of the People’s Republic of China.

Chen Kangqian, Dr Chen’s youngest daughter, said she was only three in 1942 and had no memory of her father talking about the rescue. She remembered her father as a warm-hearted man who sometimes did not charge patients for consultation and even gave them rice instead.

“I am not surprised that he could be friends with some American airmen,” Chen, now 81, said.

Professor Luo said the tumultuous political environment surrounding the second world war, and the Chinese civil war that followed it, might have led Chen to be quiet about his experience.

Dr Chen was convicted as an anti-revolutionary and thrown into a labour camp in 1951. His wife, Kong Cangzhen, killed herself after seeing others being tortured; their eldest daughter, a first-year medical school student, killed herself a year later, in 1952.

Dr Chen had his name cleared in 1954. He continued his medical career and died in 1983, a highly esteemed doctor.

Seeing a picture of her father’s calling card, Chen Kangqian said she felt very emotional.

“If I could meet Mr Macia, I would tell him how grateful I was that the card was kept so well. I am very touched that this card has been cherished by them.”

Macia, who maintained an email correspondence with Luo after returning to the United States, sent another photograph of Crew No 14 with three Chinese men before they left Guangfeng county for the No 3 War Zone Headquarters in Shangrao. He asked the professor if he could find the children of those men.

With help of local historians, Luo spent 10 days digging up local archives and was able to identify the men. Wang Fengling was an official in charge of Kuomintang (KMT) party matters; Zhang Renshi, then the Guangfeng county chief; and Zhang Mutao, then the chief of the gendarme regiment.

Wang Fengling died in 1943 and was survived by a son who is now a retired worker in Shangrao. Zhang Mutao followed the KMT to Taiwan in 1949 and died in 1985. He was survived by five children. Zhang Renshi worked in primary school education and died in 1966. Three of his four children have died; the youngest is living in the US.

“The children of the men in this photograph had little memory of their fathers – except that they recognised their father the moment they saw the picture,” Luo said. “Zhang Renshi’s daughter called me from the US and said she had never known her father was Guangfeng county chief and helped save some Americans. She felt so amazed.”

Book review – A Few Planes for China: The Birth of the Flying Tigers unravels the myth behind legendary fighter pilots

Macia, who had not expected to learn about the men in the picture his father had passed to him, said he felt very fortunate to meet Luo, and through him, the stories of these people.

“It has been very important and informative to me to understand exactly who some of those people were and their roles in saving my father,” Macia said.

China paid dearly for the rescue. Japan retaliated with massacres in at least three villages, and villagers who helped the Doolittle raiders were tortured and killed. Airfields in Zhejiang and Jiangxi endured heavy bombing and the Japanese launched a Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign a month after the air attack, which eventually saw 250,000 people in the region killed, according to Zheng Weiyong, a historian in Quzhou and author of Fall in China – Doolittle Tokyo Raid.

Some rescuers were officially recognised by the US government. Dr Chen Shenyan, who ran the Enze Hospital in Taizhou, Zhejiang, treated the injured airmen and escorted five of them from Taizhou all the way south to Guilin, in Guangxi, and Kunming, Yunnan province, was recommended to work as an army doctor and later invited by the US government to study medicine in the States, which he did: and Johns Hopkins and the University of Southern California.

President Harry Truman played Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, the 1944 movie depicting the Doolittle Raid and its aftermath, for Chen; according to Zheng, his eyes brimmed with tears when he saw himself depicted in the film.

After the end of the civil war in 1949, contacts between the raiders, their families and China stopped for decades. After the US and China officially established diplomatic ties in 1979, though, contact resumed when John Hilger, the pilot of Crew 14, sent a letter in 1987 to the Shaorang government to express gratitude. Henry Potter, the navigator from crew 1, revisited crash sites in Jiangxi and Zhejiang provinces in 1990 and met Dr Chen Shenyan again.

Over the years since, several raiders and their families have come to China, and some of their rescuers have visited the US.

In 2015 Jeff Thatcher, son of David Thatcher, engineer and gunner of Crew No 7, attended the grand military parade in Beijing commemorating the 70th anniversary of victory over Japan in the second world war.

Before attending the parade, Jeff Thatcher interviewed his father about his experience in China. David Thatcher recalled that they had been “treated like royalty”.

Plane 7, nicknamed the Ruptured Duck, crash-landed off Zhejiang province’s Nantian Island and all five crew members were injured, including two seriously. They were found by fishermen who would escort them in doolees to Sanmen and, later, Enze Hospital in Taizhou. The crew eventually travelled more than a month before reaching Guilin, Guangxi.

“They did not have anything, but they gave us all they had,” Thatcher recounted his father as saying. “We played a game of basketball with the Chinese one day. They had never played basketball before.”

After the parade, Jeff Thatcher travelled to Ningbo, Zhejiang province, with two Children of Doolittle Raiders to follow the route his father trekked more than seven decades earlier, from the beach where they landed through stops in Sanmen county, Linhai city and then Quzhou. It was an emotional experience.

“My epiphany occurred the morning I was standing on the beach on Nantian Island close to where my father’s plane had crash-landed. Like the waves crashing in from the South China Sea, I was suddenly overcome by emotion and touched deeply by the scene,” Thatcher said.

“I feel a kinship and a huge debt of gratitude to the Chinese people. If they had not rescued my father and the other members of his crew, I doubt that they would have avoided capture by Japanese troops.”

Three of the airmen captured by the Japanese were executed. Five others were sentenced to life in prison, one of whom died in prison, and the remaining four eventually were rescued in 1945.

On Thatcher’s way from the beach to the village above, where his father’s crew spent the night in a hut, an elderly woman came to him and gave him a metal fire suppression rod. It was made from the engine of the Ruptured Duck that her husband found on the beach after the crash.

Thatcher called his father and told him about the visit to the beach that morning.

“Even though we were half a world apart, I could feel his emotion through the phone,” Thatcher said. David Thatcher died a year later at age 94.

One of the few: the remarkable life and times of a former Flying Tiger

That trip prompted an idea between the raiders’ children and the local historians, to build a museum and start a scholarship at a local school. Thatcher wrote to Quzhou municipal officials to consider building a Doolittle Raid Memorial Hall and the project was agreed.

For the past two years pupils of Quzhou No 2 Middle School wrote essays in English about the Doolittle Raid’s impact on China and three recipients were to receive certificate and a cash prize in US dollars. This year all 12 shortlisted received the prize because the essays were all “creative and well-written”.

Thatcher was proud of the two projects because they brought “new chapters in the history of the Doolittle Raid in China”.

“Both of these endeavours represent cooperative efforts on the parts of our two countries to engender the spirit of friendship and gratitude that began when the Doolittle Raiders bombed Japan on April 18, 1942,” he said.

The historians regarded their dives into the archives and the sharing of memories beyond a quest for the past. Their efforts serve as a lesson for the future, especially when the two countries are sliding into a trade war.

Zheng said that the Doolittle Raiders museum reminded people of both countries that the special friendship was formed during a cruel war and that friendly ties must be nurtured.

“The American friends are grateful for the Chinese who helped them and we wanted to maintain the friendship, too. We should remember the lesson of war, not to repeat it and to let future generations continue to keep the friendly relations,” he said.