The emergence and evolution of China’s internet warriors going to battle over Hong Kong protests

- In a series of in-depth articles on the unrest rocking Hong Kong, the Post goes behind the headlines to look at the underlying issues, current state of affairs and where it is all heading

- Here we look at how young mainland Chinese are leaping the Great Firewall to get their patriotic messages across

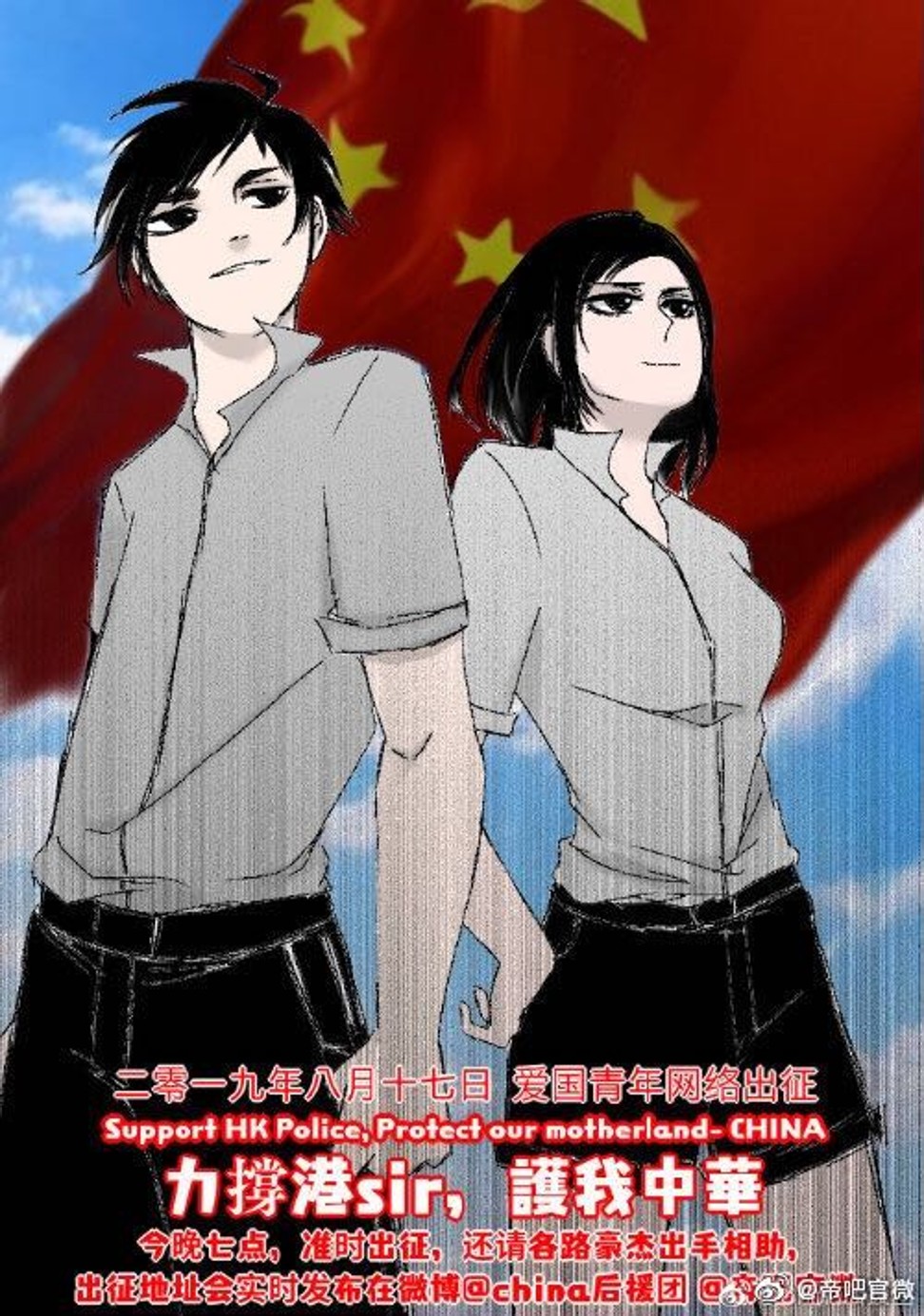

On Saturday, one of the most violent days of the Hong Kong protests so far, a virtual army launched its own attack from behind China’s Great Firewall. Thousands of memes and messages flooded the social media platforms which are banned on the mainland, all with one stated aim – to “protect Hong Kong police, protect our family”.

The action was broadcast live on Chinese streaming platform YY – from the process of getting over the firewall, to regular updates on how many posts had gone up on targeted sites, and regular encouragement to the troops to stay on the attack.

It was the most recent manifestation of a new phenomenon among China’s internet community – an alliance between Diba, the long-standing nationalist online forum whose members have been at the vanguard of the mainland’s online attacks, and its newest recruits, known as the “fandom girls”.

A college student, who goes by the pseudonym Wang Li, is typical of the new breed of internet warrior. She brings all the devotion of the fandom girl – a colloquial term among China’s online community to describe the fans who engage in en masse postings to boost the profiles and reputations of their celebrity idols – to her country, personified as “Brother Ah Zhong”.

In a typical post on Chinese social media platform Weibo, Wang recently wrote about Brother Ah Zhong’s heartbreak over his treatment at the hands of his “ungrateful children” Hong Kong and Taiwan.

“Brother Ah Zhong only has us left. He was high-born but with his fortunes gone he was bullied and his children taken away from him … When he finally fared better, he immediately wanted to take his children home.”

Wang continued – to a parade of “guard the best brother” online cheers: “But who would have thought, his children sucked up to the enemy and broke his heart. We are all he has!”

The presence of the fandom girls is a sign of how China’s online armies are evolving from previous years, when it was frequently reported that the Chinese government was paying people to censor or steer public opinion. This widespread belief led to the coining of the expression wumao or “50 cent trolls” but many of the online army’s latest recruits are young, passionate, patriotic, vocal and, they insist, unpaid.

A united nationalism front

For years Chinese internet attacks have been led by Diba, which started in 2004 as a soccer forum and has more recently become known for its highly organised nationalist “battle missions”. Its troops are divided into groups and assigned different tasks for its actions, which are always advertised in advance on their social networks.

During the attacks, some Diba members translate poems and pro-China slogans into various languages or create memes – the “ammunition” as it is known – while others are administrators, directing the “battle” from headquarters, sending out links and new materials for the troops to copy, paste and spam.

New recruits are taught how to use VPNs and climb the firewall to reach the “battlefield” – the social media pages and websites banned in China.

There is a sense of pride among Diba members. They talk about past glories – how many pages conquered, how many people assembled, how many posts per minute. They firmly believe they are presenting the truth in a united effort as they attack what they see as extremists, separatist forces or malicious rumours.

Examples of their past efforts include the 2016 targeting of Taiwan’s pro-independence pop star Chou Tzu-yu and President Tsai Ing-wen, when hundreds of thousands of Diba users flooded the comments sections of their Facebook pages.

China troll army’s battle expeditions leap Great Firewall

Last year, the group struck a Swedish TV station for hosting a show that “insulted China”, and this April it crashed the Facebook page of the World Uygur Congress.

Diba has most recently targeted prominent supporters of the Hong Kong protests, including Canto-pop singer Denise Ho Wan-sze and pan-democrat lawmaker Claudia Mo Man-ching.

Nationalism in the social media era

As the Hong Kong protests have continued, Diba’s efforts have been joined by a new breed of “patriotic youth” – the fandom girls, who previously stayed away from politics, as well as rappers and overseas students who have taken the battle off the internet and into the streets to disrupt rallies and shout curses at supporters of the Hong Kong movement around the world.

In Canada, convoys of Chinese patriots have turned up at demonstrations in Ferraris and other high-end sports cars decked with Chinese flags.

Convoys of Ferrari-driving pro-China patriots rev up Canada protests

CD Rev, a group of rappers from Chengdu in China’s southwestern province of Sichuan, took things up a notch by releasing a diss track insulting the Hong Kong protesters. The track, titled Hong Kong’s Fall, sampled US President Donald Trump’s comment: “Because Hong Kong’s a part of China, they'll have to deal with that themselves, they do not need advice.”

It went on to warn: “There are 1.4 billion Chinese standing firmly behind Hong Kong police. They will always protect Hong Kong without any hesitation. Planes, tanks and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army all gathering in Shenzhen, waiting for the command to wipe out terrorists.”

“We think the young people in Hong Kong are deluded by anti-China forces to riot on the streets. We feel grieved,” said Wang Zixin, a CD Rev member. “Because we love our country, that’s why we get angry.”

Many of the fandom girls and other new recruits to the online army refuse to be labelled as nationalists, saying they simply want to offer counterpoints to “misinformation” about China, or to protect China from being smeared. Like Diba, they find strength in numbers and work in a similar, coordinated fashion.

I couldn’t help him much but I could help with public opinion

Fandom girl Wang said she had never been particularly political, nor up-to-date on current events. Previously, she would only read news stories when they trended on social media. But this time, Wang said, she felt angry.

“I saw that Global Times reporter being treated violently [at the airport] and there were rumours about him on social media,” she said. “I couldn’t help him much, but I could help with public opinion.”

Wang told the South China Morning Post that defending her country was just like defending her celebrity idols. She did this by trying to drown out other voices with her posts, and highlighting her idol’s backstory to arouse empathy.

She said she joined the fight from time to time, in her homework breaks.

“There are hashtags on social media, such as #HongKong, where they post the bad stuff. We can’t delete that, so we just post good stuff to cover them up, so that when other people click on the tag, all they see is good stuff,” Wang said.

The “good stuff” includes tailor-made propaganda materials, memes, hand-drawn cartoons and pictures with slogans such as “I love HK”, “I love China” and “What a shame for Hong Kong”.

One popular meme reads, “The good-for-nothing youth beat up old people, beat up mainlanders, beat up journalists and are a bad influence to HK development”, while another says “Please get out of HK, please stop your violence”.

Wang refuses to be called a nationalist. “Why put a label on people?” she asked, but she affirmed her deep love for China and the amount of patriotic education she received growing up.

When she was young, Wang enjoyed school trips to the memorials of war heroes. As she grew older, she was touched by the popular web comic Year Hare Affair, which uses animals as an allegory for nations and their roles in political and military history, focusing on China’s achievements since the 20th century.

“He [China] suffered so much, I have to love him well,” Wang said.

Social media changed the symbols and forms of nationalism

One of the first commentators to identify the new breed of patriotic online warriors was Liu Hailong, a communications professor at Renda University. Writing in the Communication University of China’s Modern Communication Journal, Liu said social media had changed the symbols and forms of nationalism, and provided platforms for the mobilisation, organisation and execution of a new generation of nationalism movements.

“New media not only did not diminish differences and misunderstanding between groups, but gave birth to a ‘fandom nationalism’ where you love your country like you protect and cherish your idol,” he wrote.

The new sentiment of “fandom nationalism” makes the output of China’s modern online warriors quite different from the past, when astroturfing by private or government actors – known as “water armies” in China – was used to steer public opinion, according to Gabriele de Seta, an independent researcher based in Taipei.

Chinese police shut down trolls paid US$4.3 million to blitz websites

“Paid posts are often easy to identify, and this has led to other users calling out astroturfers as ‘50 cent’ posters, according to (largely unsubstantiated) rumours about their pay per post,” de Seta said. “In turn, these labelling wars have led a segment of users to self-label themselves as ‘self-paid 50 cent posters’, to emphasise that their positions were sincere.”

Lost in communication

The response to the activities of China’s social media warriors has been starkly divided between opinion at home and abroad. Diba’s “battle expeditions” finally caught the attention of the West, in the form of blocked accounts on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. At home, they have been widely praised by Chinese state media.

The Twitter and Facebook bans infuriated some Diba members, who accused the social media giants of a “double standard”.

“Is it spreading fake information to share mainland news? Is that what the world’s attitude towards China is?” asked one Diba user, who wished to remain anonymous.

One Diba user contacted by the Post was offended when asked what they thought of people who dismissed the group as “brats” and responded in an angry public post, which may indicate growing hostility and suspicion towards outsiders among China’s internet army.

“Why do you frame me, what evidence do you have?” the user asked. “You try to label an ordinary citizen through a coloured lens.” The user also threatened to sue and to contact the Guangdong Journalists’ Association to complain about the reporter’s “breach of ethics”.

In contrast, Diba members were excited to make the prime time news on state broadcaster CCTV, which reported on August 18: “Stopping the riots and chaos is the united demand of 1.4 billion Chinese. More and more people decide not to be silent any more, saying a firm ‘no’ to violence, guarding Hong Kong with their actual actions.”

State endorsement for Diba has been a long time coming. Its past attacks did not generate a great deal of attention from official media, which also struggled to put a name to the phenomenon.

Facebook, Twitter say Beijing backed campaign to disrupt Hong Kong protests

Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of Global Times, said in 2016 – after a Diba attack on Taiwan social media sites – that it was a “special but earnest communication process” between young people across the strait.

“I don’t encourage mainstream media to clap and cheer for Diba’s ‘expedition’, there’s no need,” Hu wrote on Weibo. “But I also oppose the intellectuals who scold and reprimand the young. That kind of suppression is a twist of facts, it’s ugly. We just need to respect their kind of carnival.”

Chinese state media has previously downplayed Diba’s efforts, for fear they would further degrade cross-strait relations and also because authorities tend to keep nationalism in check before it erupts into actual violence, according to de Seta. But, this time, he noted, the situation was different.

Beijing is endorsing the online armies because patriotism works.

Chinese envoy in New Zealand praises ‘patriotism’ of pro-Beijing students

“It helps prop up the [Communist Party’s] legitimacy at home by postulating external enemies or the threat of separatism while also strengthening China’s image in foreign affairs by providing a public opinion profile that fits the official narrative,” he said.

A Chinese internet governance official, who declined to be named because of the issue’s sensitivity, praised Diba as a group of patriotic youth who wanted to tell the world the truth, and which had the support of the Chinese people.

“The Western media has often showed bias and even smeared its image, because that made it politically correct, made it popular, while saying the truth or supporting China was believed to be communist and excluded,” he said.

But whether these groups are creating understanding or, at the least, effectively communicating with their audience outside China has come under question with the rise of the patriotic “fandom girls” and their ilk.

The anonymous Diba user said it was something he had been mulling over recently and suggested that the way the group organised its expeditions in future may change. “Definitely not simple copying and pasting texts any more,” he said.

But he had no doubt the attacks over the Great Firewall would continue. “At the moment, the whole world is fighting for the right to discourse, fighting over public opinion,” he said. “China has stayed quiet long enough.”

Other parts of this series have examined what Hong Kong protesters really want, why protesters view the police as the enemy, how Hong Kong police are holding the city back from the brink, how leaders have spurned the chance to listen to public opinion, how Beijing keeps getting Hong Kong wrong, and the trouble with trying to turn Hong Kong’s young people into ‘patriotic youth’

.jpg?itok=H5_PTCSf&v=1700020945)