Advertisement

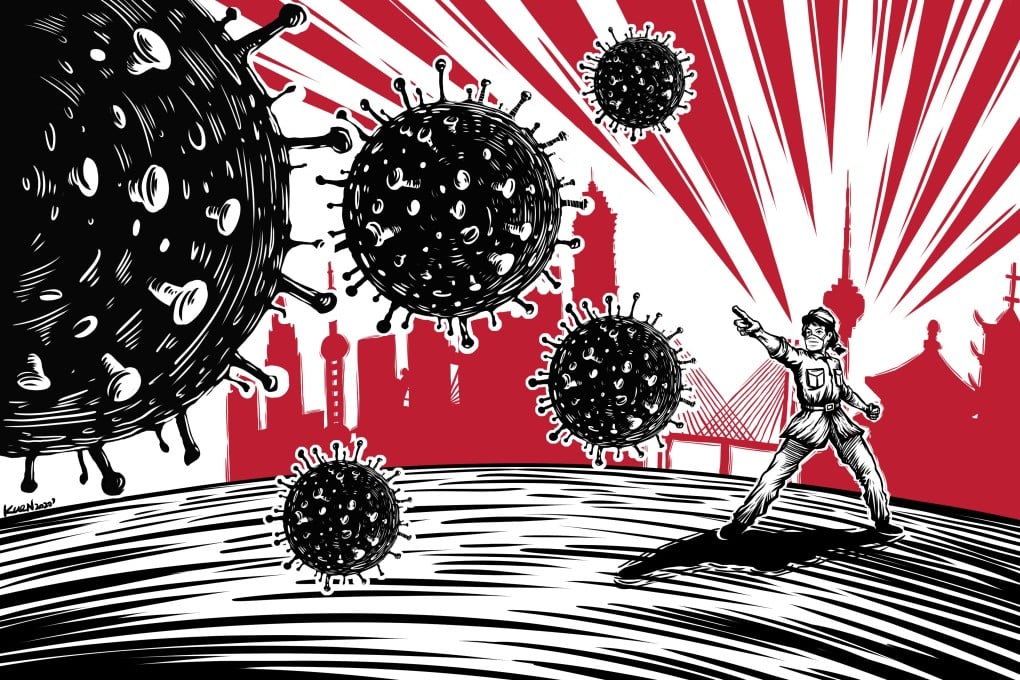

In the firing line: the women in China’s war on the coronavirus

- Vice-Premier Sun Chunlan has been the face of the Politburo in Wuhan for more than a month, and she’s under mounting pressure

- She may be seen as more able to win trust in a country that usually ‘relies more on the men for their aggression and confidence to rule’

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

China’s former leader Mao Zedong famously declared that “women hold up half the sky” – a propaganda slogan first used in 1955 to encourage more of them to work in rural cooperatives, plough the fields, plant rice and help boost agricultural output.

In the country’s war on the coronavirus, women are taking on the tough jobs and holding up half, or even more, of the sky, analysts and feminists say – though they are also in the firing line for blame, and at the centre of a controversial state media campaign.

The highest profile is Sun Chunlan, vice-premier in charge of culture, education and public health and the only woman in the ruling Communist Party’s 25-member Politburo. The 70-year-old has spent more than a month on the front line in Wuhan, Hubei province, where the new virus strain first emerged in December, leading the government’s response on the ground.

Advertisement

She has been the stern face of the Politburo in the crisis, seen in state media talking to medical staff, stressing the importance of admitting patients to hospital and treating them as quickly as possible, checking on progress of new facilities being built, and warning local officials that “there must be no deserters, or they will be nailed to the pillar of historical shame forever”.

Advertisement

Ding Xiangyang, deputy secretary general of the State Council, China’s cabinet, reinforced Sun’s message to Hubei officials at a press conference in Wuhan on February 20.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x