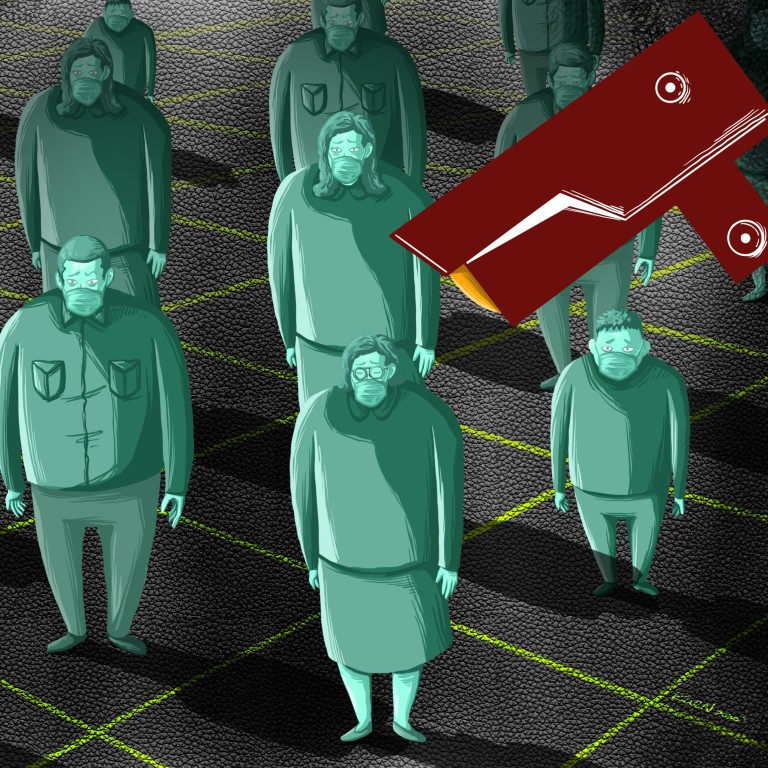

Street by street, home by home: how China used social controls to tame an epidemic

- Neighbourhood monitoring system is at the heart of restrictions imposed ‘at the expense of public autonomy and vitality’

- Chinese city has eased restrictions, but measures remain in place for community ‘cells’

One of them, 75-year-old Jiang Hong, said the last three months had been just like life in the Mao Zedong era.

“It’s déjà vu really – a throwback to the 1960s when we lived in the people’s communes and everything was taken care of but you didn’t have much choice,” the retiree said.

But in 2020, she said officials used smartphones instead of loudhailers to get their message across. And people no longer relied on the food coupons widely used in China in the ’60s to buy essentials.

Like many elderly residents, Jiang had to learn to use social media app WeChat to adapt to her “new collective life”. All the residents in her community “cell” are connected through a WeChat group where they receive government messages and make payments online. These cells make up a grid-based neighbourhood monitoring and management system that exists across China.

Jennifer Pan, an assistant professor of communication at Stanford University, described it as an “upgrade of the urban household unit management system” that has been in place since the Mao era.

According to independent political analyst Chen Daoyin, the model is “a modern version of the centralised autocratic controls that have been in place in China since the Qing dynasty”.

He said it brought together the household registration system and network of neighbourhood committees that were introduced soon after the founding of communist China in 1949 – and internet technology had taken it further.

“[China can do this because] it is a centralised autocracy, otherwise such a system would be very difficult to manage,” Chen said.

“In addition, [this pandemic] is a national crisis that has allowed [the state] to justify its draconian controls,” he said. “But this comes at the expense of public autonomy and vitality.”

‘Waterproof surveillance’

Like 11 million other people across Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, the Jiang family have been under “grid management control” since January 23.

That means “waterproof surveillance” and monitoring within their community, or xiaoqu. Jiang said the apartment blocks in her compound were sealed off and all residents had to enter or leave via a single gate that was guarded around the clock.

Although Wuhan ended its lockdown early this month and reopened its borders, community control measures have remained in place.

The measures are wide-ranging. Every day, residents like Jiang must report their temperature to the official in charge of their community and provide updates on their whereabouts.

The “grid controllers” are under strict orders to monitor all residents and report anything unusual. But they are also supposed to provide supplies for residents, meaning those who do not comply with the rules could miss out on grocery orders.

Jiang’s daughter, Dorothy Wang, spent a lot longer with her parents than she was anticipating after she travelled to Wuhan for the Lunar New Year holiday in January. The 45-year-old has only just made it back home to Beijing.

She said the first month under lockdown was “chaotic”.

“No one knew what to do after [the lockdown] was announced,” said Wang, an admin manager for a medical equipment supplier in the capital. “Most people in this community are retired and they had no idea what was going on.”

All under control

That started to improve in mid-February, according to Wang, when the Wuhan government sent some 44,500 civil servants to more than 7,000 residential areas across the city. Their job was to help the 12,000 grass-roots officials managing the mass quarantine effort.

The city’s new Communist Party boss, Wang Zhonglin, also told the cadres to locate all suspected Covid-19 patients and get them into isolation as Wuhan struggled to contain the crisis.

Build-up to coronavirus lockdown: inside China’s decision to close Wuhan

Dorothy Wang said the change was noticeable when the civil servants were brought in.

“It was like something out of a prison drama,” she said. “Every family had an allotted time to take a stroll in the garden of the compound. People from the estate management and the residential committee were watching to make sure only one family was out for a walk at any given time.”

Community officials also organised patriotic activities such as virtual flag-raising ceremonies and online karaoke and fitness contests in a bid to boost morale.

Such officials are crucial to the success of the system, according to Pan from Stanford University.

“In some neighbourhoods, the grid controllers are very good at their jobs, but some are terrible,” she said. “How well these cells function varies widely across the country.”

While some international epidemiologists have questioned the effectiveness of the largest quarantine in human history – it was extended to nearly 60 million people across Hubei as well as other parts of the country – Chinese health authorities have reported few or no local transmissions of the virus since March 17. Most new Covid-19 cases have been imported since then.

The World Health Organisation praised China’s measures after a joint mission to the country on February 28. “China’s bold approach to contain the rapid spread of this new respiratory pathogen has changed the course of a rapidly escalating and deadly epidemic … this decline in Covid-19 cases across China is real,” the WHO said in a report.

As the virus has rapidly spread across the globe, similar lockdowns have been imposed in many other countries. But China’s system of neighbourhood control and surveillance enabled a more extreme response.

Jeremy Wallace, an associate professor of government at Cornell University, said the system had been “integral to China’s massive data gathering response to the crisis, mainly through fever checks and monitoring compliance with severe social distancing policies”.

‘Uniquely Chinese’ response

Observers said the draconian measures taken in Wuhan played a key role in China’s containment of the virus, but the “uniquely Chinese” controls were not possible elsewhere.

Without the social controls that exist in China, Pan said countries like the United States relied on institutions such as “neighbourhood watches, schools, churches and community non-profit organisations that can help mobilise the population to fight a pandemic such as Covid-19”.

Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, also noted that most Western countries did not have Beijing’s top-down governance structure, and that Chinese culture emphasised the collective good rather than individual freedom and privacy.

Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London, agreed.

“It would be very difficult to [make this] work in a democracy. The implications on the intrusion against individual rights and privacy are serious and few democracies would accept such a system except as an emergency measure for a very clearly defined limited period,” he said.

No lockdowns: how Hong Kong and South Korea are beating Covid-19

Wu noted other countries had managed the crisis without a full lockdown.

“South Korea has done extensive testing like China. South Korea was quick to tap its mobile communication technology to avoid a costly full lockdown,” he said. “Another key point is sharing information regarding all cases in a timely and transparent fashion.”

South Korea had reported more than 10,600 infections and 236 deaths as of Tuesday, with new daily cases continuing to fall below 100.

“Apart from the China way, there are better models with less economic and social cost,” Wu said. “It is just a matter of what’s doable and suitable.”

This is one in a series of articles that examine the early lessons learned from the Covid-19 pandemic.