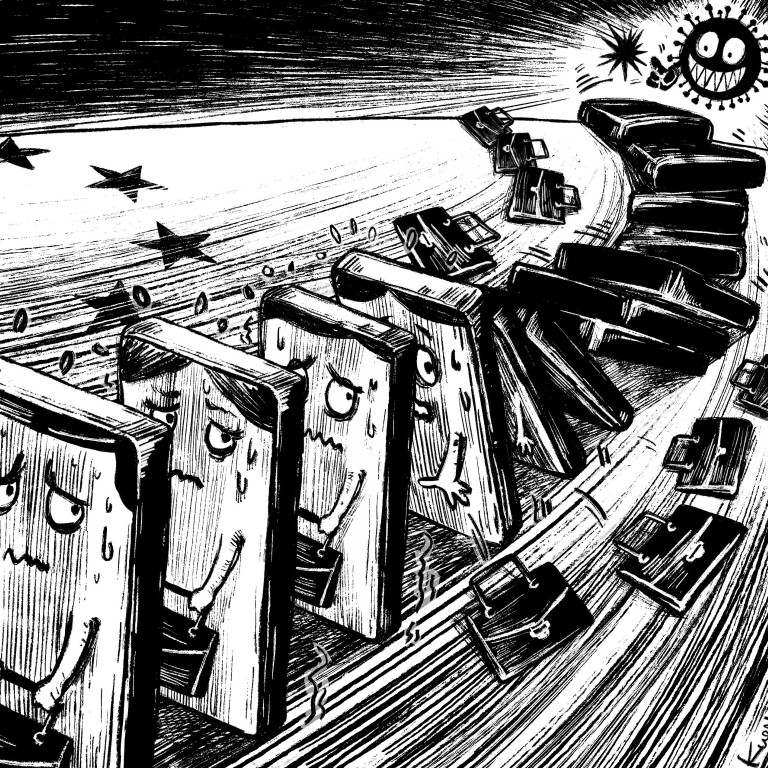

Class and the coronavirus: as China’s wealthy cut back on life’s luxuries, the nation’s poorest are in a fight for survival

- Migrant workers and the residents of rural areas are bearing the brunt of the employment crisis in China caused by Covid-19

- And while many factories in the nation’s industrial heartland have reopened, a slump in global demand for Chinese goods has dimmed hopes of a swift end to their problems

This is the fifth in a series of six stories exploring the causes and consequences of the unemployment crisis China may face following the coronavirus pandemic. This instalment looks at how people are coping in different parts of the country.

Li Ming, a 36-year-old marketing manager for a car company in Beijing, is feeling the pinch for the first time in her life.

“Suddenly half of our household income evaporated,” Li said. “I haven’t had a decent sleep for months. We have a mortgage to pay and two children. They are a heavy burden now.”

Li was able to save 12,000 yuan (US$1,700) a month by sacking the family’s domestic helper.

“After a long pause, she agreed. She didn’t say anything else but sent her love to my kids whom she has been with for three years.”

Besides the human cost of the Covid-19 pandemic, economies have stalled and few people are likely to come out of it unscathed. But while middle class families face the prospect of giving up their luxuries, those already at the bottom of the income pile are facing potential disaster.

But economists say the worst has yet to come for China’s massive labour force.

According to a report by The Economist Intelligence Unit on April 22, China’s unemployment rate could reach 10 per cent this year, with the loss of a further 22 million jobs in urban areas.

UBS estimated in a report published last month that 50 million to 60 million jobs had been lost in the services sector, and a further 20 million in the industrial and construction sectors.

While China’s official unemployment rate is based on data collected from 31 major cities, the situation in smaller inland cities and rural areas is believed to be worse, where social distancing measures could be the last straw for ailing businesses in vulnerable industries and the service sector.

“China’s regional disparity is huge,” Hu Xingdou, an independent political economist in Beijing said. “While people in big cities and coastal regions are struggling to maintain their normal life, those in inland provinces and poverty-stricken areas risk losing their lifelines or already lost them.”

Peng Lixiang, a 38-year-old from the village of Dayi in Shandong province, used to work at a hotpot restaurant in Heze, one of the poorest cities in the east China province, earning about 1,000 yuan a month.

But the business took such a blow from the health crisis that the owner decided to shut up shop in February, and Peng found herself out of a job.

As the family’s main breadwinner – her husband is an odd-job man who works only occasionally – Peng said she was struggling to find the money she needed to raise her eight-year-old daughter and repay the loans they took out to build their home.

She said she had applied for jobs at factories and restaurants in the city but faced nothing but rejection.

“I didn’t expect it would be so difficult,” she said. “I’d take a low salary, hard work or anything else, as long as I don’t have to work at night because I have to take care of my daughter. I just need a job.”

Peng is not alone in finding work hard to come by in China’s less affluent inland towns and cities. That is why millions of migrant people, like 39-year-old Cao Jin, are heading back to the coast after months of living in lockdown.

On April 1, Cao set out from Suizhou, a city in northern Hubei province on a high-speed train to Guangdong, the country’s manufacturing hub, where he hoped to resume his work as a production line supervisor for a company in Foshan that makes heating plates for electrical appliances.

But after spending 12 days in precautionary isolation in the factory dormitory, Cao was told the only job available to him was on the night shift – working from 6pm to 4am, five days a week for the government-stipulated minimum salary of 2,000 yuan a month – or about a quarter of what he used to earn.

“It’s far from enough to cover my living costs in Foshan, let alone support my family in Hubei,” he said.

Wuhan orders coronavirus tests for all residents as second wave fears grow

Cao said he tried to reason with his boss but was told that because of a 50 per cent slump in orders the factory owners had decided to cut its production lines from 10 to five. The size of the workforce had also been halved, to about 300.

“I was left with no choice but to resign,” he said.

Cao said he spent the next few days looking for work in Foshan but without success. Friends and former workmates told him the dip in foreign demand for Chinese goods had affected the entire supply chain.

Foshan is home to scores of household appliance manufacturers that rely on foreign markets for much of their sales. One of them, Midea Group, reported a 23 per cent drop in revenue in the first quarter of the year, while Gree Electric Appliances, based in Zhuhai – a city about 120km to the south – saw its revenue fall by almost 50 per cent in the same period, mostly due to weak exports.

April saw a 3.5 per cent year-on-year gain in exports, as some of the country’s trading partners emerged from lockdown, but much of that was attributed to a low base from last year.

Rosealea Yao, an analyst with Gavekal Dragonomics, said the trajectory of China’s recovery would remain “fairly shallow” due to knock-on effect of weaker global demand.

“Exports were better than expected in April, but new orders are plunging and the full hit from the collapse in growth in the US and Europe has yet to materialise,” she said.

“Job losses in export manufacturing are likely to worsen rather than improve.”

A report by Fitch Ratings this week said that the impact on the global economy of the health crisis was adding to the pressure on China’s labour market.

Even though Beijing has tried to shift the domestic economy more towards consumer spending and the service sector, a large proportion of Chinese jobs are still linked directly to foreign demand. Based on figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the company put the absolute figure at 87 million in 2019, of which 61 million were in manufacturing or services.

“The authorities’ policy steps to accelerate infrastructure projects may provide some domestic employment offset for the potential job losses associated with the sharp decline in external demand in 2020, but this is unlikely to neutralise these losses entirely,” the report said.

The impact on the labour market was likely to be worse than suggested by the official unemployment figures, and the situation was unlikely to improve for some time, it said.

“China’s various household income aggregates (household disposable income, migrant worker incomes, personal business income), many of which turned negative during the first quarter of this year, could remain so for yet another quarter.”

Migrant worker Cao, who has spent more than a decade in manufacturing, said he had never before encountered such a difficult jobs market.

“I don’t know if the economy will get better next year, but I definitely won’t be working in manufacturing again this year after seeing so many jobs and production lines cut at factories.

“I’ll probably go to some northern city and get a job as a decorator,” he said.

That might be a wise choice, as the property sector has shown signs of an upturn, thanks to cheaper and more readily available loans, coupled with government policy changes.

“The recent hukou [household registration system] and land reforms may bring additional property demand and construction, along with the government’s plan to double old town renovation,” Wang Tao, an economist at UBS, said.

However, the outlook was clouded by the impact of Covid-19 on household income, Wang said.

According to the figures from the National Bureau of Statistics, urban residents’ disposable income in the first quarter fell 3.9 per cent year on year to 11,691 yuan, while the figure for rural residents dropped by 4.7 per cent to 4,641 yuan.

The final instalment in our series looks at the technology sector and how the global health crisis has affected the flow of foreign talent into China.