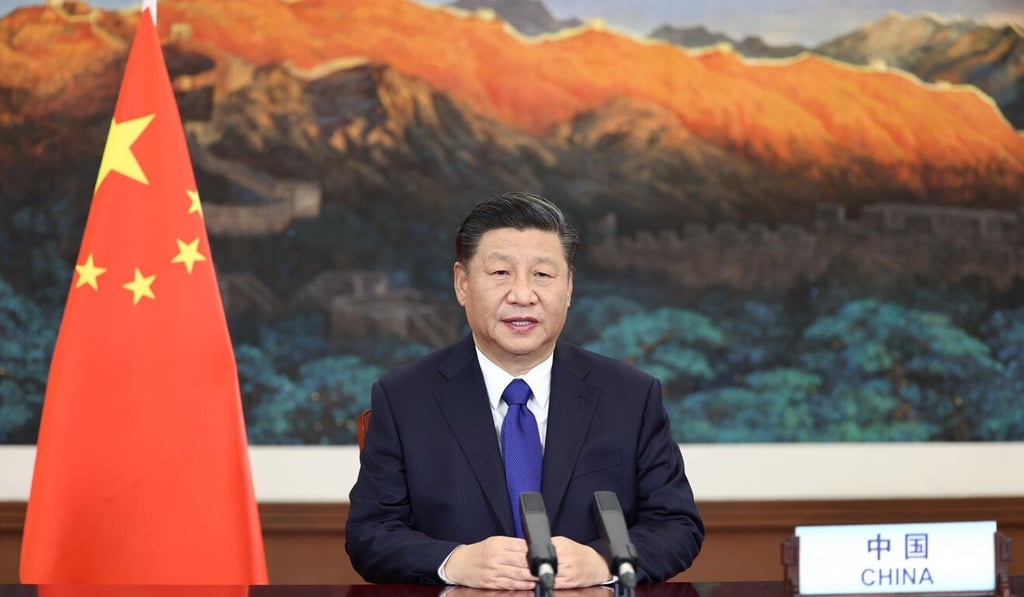

China is global leader in imprisoned journalists for a second consecutive year, watchdog group finds

- China held at least 47 journalists in jail this year, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, just shy of the 48 it had in prisons in 2019

- About half this year are Uygurs reporting on conditions in Xinjiang, a CPJ official says

China has topped the global ranking of imprisoned journalists for a second year in a row, according to new analysis by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a press freedom watchdog.

At least 47 journalists were imprisoned in the country as of December 1, including those jailed this year as well as those serving longer sentences, according to a CPJ report published on Tuesday. Last year, that number was 48, according to CPJ, which is based in New York.

“Many of these journalists [in Xinjiang] are in jail for things like being ‘two faced’, which means, of course, in name supporting the Communist Party but [being] accused of undermining it in secret,” said Butler, the group’s Asia programme coordinator.

China’s place atop the rankings comes as global figures reached a new high, with at least 274 journalists around the world in prison this year for their work, eclipsing a previous record of 272 set in 2016.