Getting to the root of the problem with Hong Kong's trees

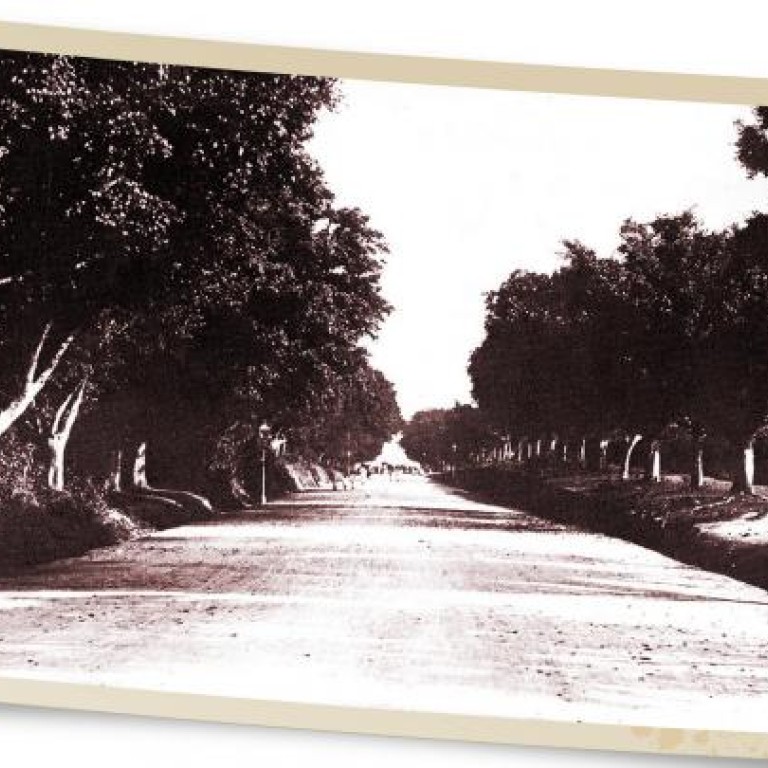

The rickshaws and horses seen in old pictures of Nathan Road are long gone - and unless the city changes its ways, the banyan trees will be too

According to the latest figures obtained from the Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Hong Kong has lost one-tenth of its urban heritage trees in the past eight years. Of the 527 trees listed in the department's register of "old and valuable trees" since 2004, 52 of have been removed because of "natural causes", by which the department means typhoons and disease.

While the government blames the loss on the age of the trees, experts and at least one former official say it is the government's poor maintenance that has weakened the health of them in the first place. Critics say that if the government continues its neglect of the problem, which stems from a lack of vision and qualified professionals, the city could soon lose all its heritage trees.

The issue became a matter of public concern over the past few summers, particularly in August 2008, when a coral tree plagued with fungus collapsed in Stanley Market, killing a schoolgirl. The accident exposed the government's failure at assessing tree risks and triggered a series of follow-up actions taken to improve the system, including setting up a tree-management office two years ago.

A weakness in the city's tree-management system has been a lack of co-ordination among departments. This stems from the government's "integrated" approach, under which the location of a tree will decide which department is responsible for its care.

For example, a tree located on a highway is managed by the Highways Department, while those in public parks are left to the Leisure and Cultural Services Department.

The tree-management office was set up to improve risk assessment and the standards of tree workers. It has issued guidelines and organised training, with More than 14,000 tree workers and supervisors attending its workshops and seminars in the past two years, not including staff from various departments. But a tree professor at the University of Hong Kong, Jim Chi-yung, who is also a member of the office's expert panel, said it had not functioned properly and had failed to live up to public expectations.

"The office, in the face of repeated accidents, was under tremendous pressure to identify risky trees at the time it was set up," he said, "But the brief training sessions given to staff and workers won't turn them into tree scientists."

According to Jim, sessions were held in the form of two days in a classroom and a half-day field trip.

The assessment method adopted by departments is also described as unreliable, because it is based on a common misconception. "The belief is that trees with dense foliage are healthy. In fact, there's no direct linkage between external appearance and structural soundness," Jim said.

"What we need are tree specialists, not a large number of insufficiently trained 'assessors'," he added.

Giving the office's head the most junior rank, D1 in a system that is scaled from one to 10, has also made it more difficult to advise senior officials. This is a serious failing when urban trees are managed by different departments, and co-ordination among officials is essential.

Jim's study of the more than 50 heritage trees lost from 1993 to 2003 showed that their deaths were mainly caused by harm sustained in roadwork and construction activities, which damaged their roots and disturbed the soil. "With tree authorities and responsibilities in the city scattered between 12 departments, among which there is little effective co-ordination or strong leadership, it is not surprising that tree work is commonly pushed to the sidelines," he wrote in a scientific journal.

The government did set up a steering committee comprising 12 department directors and two commissioners in transport and tourism to ensure "seamless integration" from planning to management. But the Development Bureau says members have only met three times since 2010.

Before the expansion of the expert panel - set up under the Tree Management Office - to include more biologists and arborists early last week, Jim was one of only two panel members who did not work in the government. Of the five non-official members, three are former government officials, raising questions about the panel's independence. At the panel's five meetings held in the past two years, Jim said experts were asked to endorse the removal of risky trees, rather than being solicited for advice on preventive measures. "It is disappointing," he said.

Despite the setup of the office, accidents involving fallen trees still occur. The latest injured five pedestrians on Park Lane Shopper's Boulevard in July, when a diseased heritage tree suddenly fell in fine weather. According to the definition of an old and valuable tree, the government's official name for a heritage tree, it should have a trunk diameter of greater than one metre, be from a rare species, be more than 100 years old, be of cultural or historical significance, or have an outstanding form.

Guidelines have been formulated to regulate construction work that may threaten the health of such trees. While the guidelines have offered them some protection from infrastructural works, many of the trees are now threatened by an infectious disease that has ravaged populations in Taiwan and Japan. The disease, brown root rot, is caused by a fungus that eats roots and weakens wood texture. It has already killed at least seven old and valuable trees on the register, including the one that fell on shoppers' boulevard, and is suspected to be the cause of three other suspicious tree deaths. Two infected banyans, in Kowloon Park and on Nathan Road, are also struggling to survive.

The source of the contagion is believed to be the dying banyan tree in Kowloon Park, which was named as the most majestic tree in 1997 in a public vote. Experts say the disease has spread quickly, through the air and soil, due to government negligence.

"The tree office does have guidelines for treating the disease. But who follows them? Are contractors made aware of them?" asked the chief executive of the Conservancy Association, Ken So Kwok-yin. According to guidelines uploaded onto the office's website, the remains of infected trees should be burned and their soil should be replaced. But observations by the and tree experts found that remains had been left uncovered for weeks before removal.

The disease has now spread to trees in the Observatory, a rare oasis in the city next to Nathan Road, but the government has yet to conduct a comprehensive survey on the extent of the city-wide outbreak. And it has yet to be on the agenda of the expert panel.

"The disease is not incurable. The government may not have to remove the trees. They should try to save them first," said Professor Chiu Siu-wai, a fungi specialist at Chinese University. Chiu said the university had already identified a cure in the laboratory, but the city's lack of tree pathologists had forced the government to rely on experts from Taiwan, who visited Hong Kong on request.

"We should train up our own specialists, beginning with university education," Jim said, "When Singapore was determined to embark on their greening plan 50 years ago, they built up their local team by sending it overseas for education. Now they can even export their expertise."

To replenish the lost trees, the leisure department has added 13 trees to the heritage register in the past few years, including banyan trees in Kwun Tong, Yuen Long and Kennedy Town that increased the total number of old and valuable trees to 484 as of last month.

Town Planning Board member Patrick Lau Hing-tat, a veteran landscape architect who chairs the Hong Kong Trees Conservation Association, said the city needed a comprehensive master tree plan, and an element of public scrutiny to ensure that it was realised.

"Hong Kong has developed lots of 'long-term' greening plans, but few are followed up by departments," Lau said, "One of them proposed turning Hennessy Road into our version of Orchard Road in Singapore when redevelopment opportunities arise. But new buildings along the road still leave little room for tree planting."

Lau proposed setting up a forestry commission, like to the Harbourfront Commission, to allow public participation and to monitor government greening plans and tree-management work. It would also co-ordinate the work of various departments.

"The present system hardly works. The handling of infectious tree remains is an example. Although the trees in Kowloon Park are managed by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department, treating contaminated soil falls under the responsibility of the Environmental Protection Department, and clearing the remains of trees is done by the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department," Lau said.

He said the association had started offering accreditation to tree managers, who could assess the risks to trees and supervise construction work, in the hope the government would set an example for developers by hiring these professionals as field officers to supervise public projects.

"We hope similar accreditation would be offered to tree workers by the government, to ensure their quality," he said, "These workers should be well-trained and offered a career with prospects."

A former government official familiar with tree management works said a shortage of manpower and a lack of qualified workers was plaguing the government, which sometimes asked cleaners and security guards to do tree work.

"The risk of climbing up a tree is no less than that of workers erecting scaffolding. Why do only the latter require examinations and qualification?" the former official asked.

A spokeswoman for the Development Bureau said the government aimed to introduce a qualification framework for tree specialists, managers and skilled tree workers, meaning they would be required to obtain qualifications. As the first step, the bureau is reviewing the need to tighten the technical and management criteria for government landscape contractors.

But Jim said the city needed a serious discussion about new laws for tree protection. Former development chief Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, now chief secretary, told lawmakers in a debate on tree management last year that the government would consider a study on introducing a bill for trees.

"I hope she will honour her words," Jim said.