Legendary journalist Clare Hollingworth, who broke the news of the beginning of the second world war, dies in Hong Kong at 105

The war correspondent reported on conflicts around the world but her biggest story was her scoop on the start of the second world war in 1939

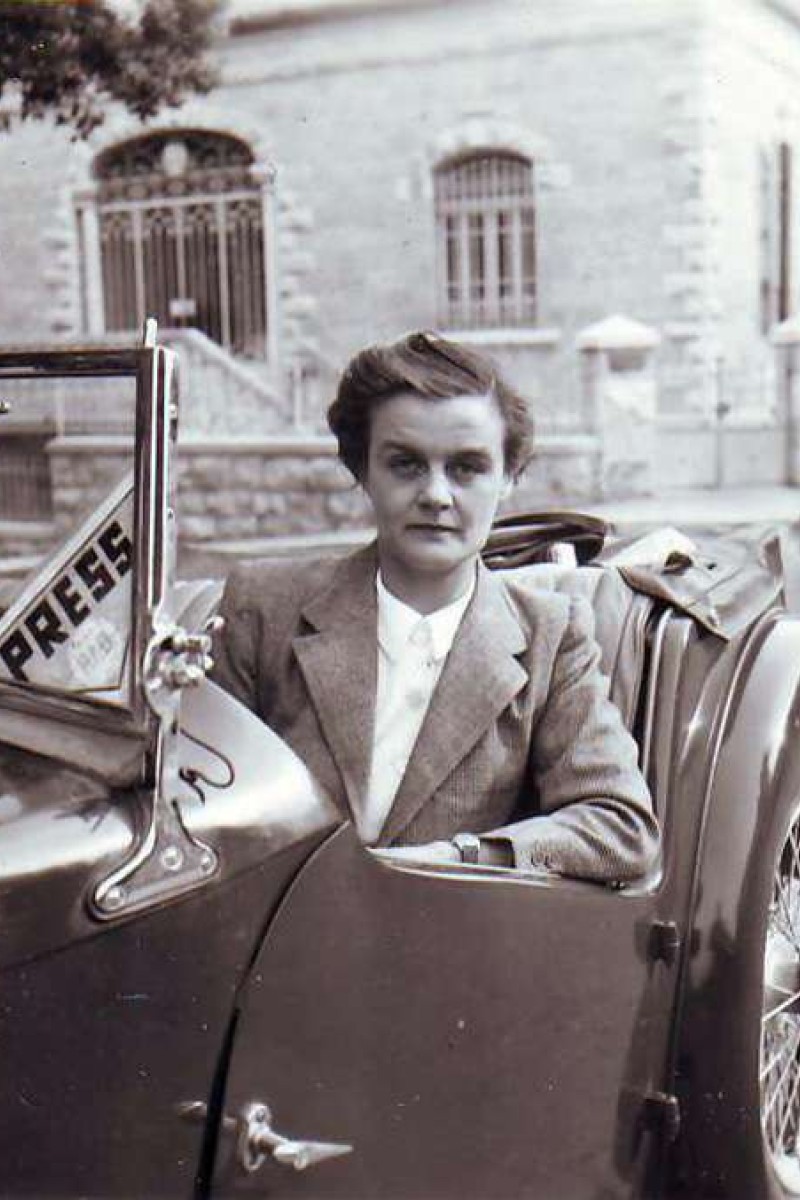

Journalist Clare Hollingworth in a press car.

Journalist Clare Hollingworth in a press car. Famous journalist Clare Hollingworth has died at her home in Central. She was 105.

Hollingworth was a war correspondent. She covered conflicts in Vietnam, Algeria, the Middle East, Pakistan and India. She also covered the mainland’s Cultural Revolution.

Her biggest story, however, is her scoop on the start of the second world war. She was the reporter who broke the story of Germany’s invasion of Poland.

Hollingworth, who spent her final years in Hong Kong, was born in Britain. She cheated death a few times during her career, but on Tuesday night she was found by her domestic helper to be not breathing. She was taken to hospital and declared dead.

When she was 27 in 1939, Hollingworth had just started to work for Britain’s Daily Telegraph newspaper when she filed her major scoop. As can be imagined, there were not many female journalists at the time and even fewer who were willing to be war reporters.

In fact that wasn’t what she had in mind when she was hired by the Telegraph. She was in Poland to write about refugees. She had worked with a charity there for five months, helping thousands of refugees trying to flee the Nazis.

She was in Poland when the border was closed to everyone except diplomatic vehicles. The plucky woman borrowed a British consul-general’s car and headed to Germany. When she told him where she wanted to go, he laughed. “You’re a funny girl,” he said. The border guards even saluted her when she passed.

There, according to a story in the Post Magazine, she decided to do some “retail investigation”.

“In a chemist’s shop where I tried to buy some soap,” she wrote later, “I was told they had to send the entire stock to Berlin.”

Then, as she drove between the towns of Hindenburg and Gleiwitz, she was passed by scores of official messengers on motorbikes.

A massive screen of sacks had been built to shield the valley below. She wrote in her biography that the sacks had been blown by the wind and she could see what was going on below. There were the tanks, armoured cars and weapons that were being massed in readiness for the invasion.

“I guessed that the German Command was preparing to strike to the north of Katowice and its fortified lines and this, in fact, was exactly how they launched their invasion in the south.”

The story was published, but her byline was not.

Three days later she was woken by the sounds of the Luftwaffe, the German air force, bombing the town. She called the British Embassy in Warsaw, but the person she spoke to wasn’t sure she was telling the truth.

“ ‘Listen!’ I held the telephone out my bedroom window. The growing roar of tanks encircling Katowice was clearly audible,” she recounted in her autobiography. “Can’t you hear it?”

She hated being treated differently for being a woman, but at the same time hated it when women demanded they be treated differently. She found that if a woman stopped to do her make-up or her hair, it made it more difficult for others who were just there to work.

During her career she would speak to spies and shahs, kings and presidents, and she would treat them all the same.

She liked and respected the British generals Wavell and Auchinleck, but she hadn’t much time for Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, the most famous of them all. That was because Monty hadn’t too much time for her, believing women reporters should be kept away from the front.

At the end of the desert campaign, shortly after he captured Tripoli in Libya in 1943, Montgomery ordered Hollingworth, by then working for the Chicago Daily News and following him with the rest of the press pack, back to Cairo. So she went to join US Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower and the Americans in Algiers. “I said, I can do anything a man can do: use a man’s loo, sleep on the floor.”

From her base in Cairo, Hollingworth travelled widely during the war: to Palestine, Iraq and Persia (where she got the first interview with the new shah, 21-year-old Mohammed Reza Pahlavi). She got a pilot’s licence – “to help me understand air warfare” – and learned to parachute jump (though it was too safe and controlled, she said, to be terribly exciting).

While covering the Algerian war for independence in 1962, Hollingworth stood up to members of a French far-right group who rounded up foreign journalists and threatened some of them with execution. The rebels were hunting an Italian journalist.

“I was extremely annoyed at this treatment and I told their commander in French, ‘Go away at once, monsieur, or I will have to hit you over the head with my shoe, which is all I have.’ ”

The rebels then bundled the Daily Telegraph reporter John Wallis into the back of a jeep to be driven off to his near certain execution. Journalist biographer and historian Tom Pocock was there too. “Clare turned like Joan of Arc to the rest of us standing with our hands up. ‘Come on!’ she said, ‘We’re going too! They won’t shoot all the world’s press!’ So we all marched out and started climbing into the jeeps.” The rebels let them all go, he said.