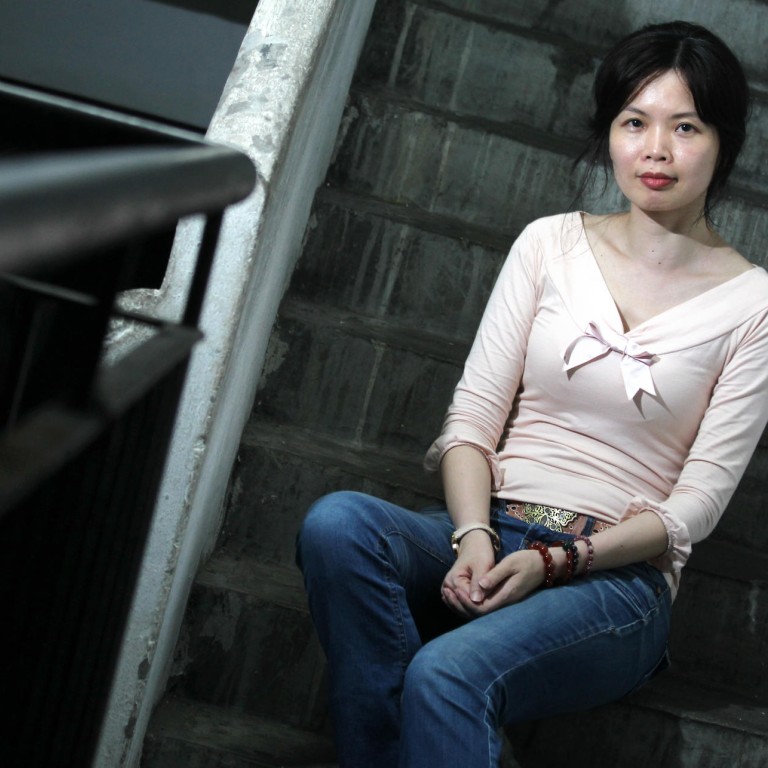

Fighting poverty and prejudice on behalf of migrants

Sze Lai-shan came to the city as a child with virtually nothing. Now she uses her personal experiences to help migrants find their feet

Sze Lai-shan came to Hong Kong as a child from the mainland, so she can empathise with the new immigrants with whom she works these days and the difficulties they face. Sadly, though, Sze reckons there is more prejudice nowadays than in her childhood.

Sze, a community organiser for the Society for Community Organisation (Soco), runs its new immigrants project. She's also known for her campaigns for more accommodation for the homeless and her efforts to eradicate cage homes - an issue that has gone to the UN.

"We were particularly concerned about children living in these conditions," she said.

Cage homes still exist in Hong Kong despite negative press coverage because, says Sze, the government insists that there is market demand for this kind of accommodation.

Sze also knows what it is like to grow up in a low-income family.

"I grew up in a 'cubicle' - we would share the kitchen and toilet with other residents. We lived like that for at least six years after I arrived. I would work after school doing handicrafts," she said.

That involved putting little crystal "diamonds" onto watch faces for decoration.

Lack of housing is still a chronic problem in Hong Kong, says Sze. With recent reports showing that 1.16 million people live in poverty in the city, the rate at which public housing is being built is too slow, she says.

Sze has a degree in social work from Baptist University, which she followed with a master's degree in human rights law.

As a child she wanted to be a businesswoman, or maybe a journalist to highlight injustices. But then she was inspired by social workers who not only would help people in dire need, but empower them and give them a voice.

There needs to be more work done on providing mainland immigrants with equal opportunities, says Sze, and ensuring that the law recognises that they are being discriminated against and protects their rights.

Sham Shui Po has an immigrant mutual aid association, which has its own leader, says Sze. It is open every day and is a venue and opportunity for immigrants to help one another. Sze is also proud of a children's rights association that has been set up.

"It has nearly 2,000 child members who choose their own leader. All the children are from poor, underprivileged families."

Volunteers take some of the poorer children to visit other parts of Hong Kong to broaden their knowledge of their home city.

"We also advocate women's rights," says Sze. "There is a lack of childcare services in Hong Kong."

The more projects there are, the more Sze is involved. It is her life. Perhaps it is difficult to say no. But Sze sees it in a different way - as preparing for the future.

"We cannot foresee how the future will be, but I think we will make that future better if we prepare well," she said.

She loves to see the empowerment of new immigrants, women and underprivileged families and feels she can act as a role model - if they are working hard, then so should she.

"These are quite hard times, so every year there is an extra workload. But I'm still young and healthy so I do as much as I can. I consider it a blessing. Sometimes I'm quite angry with the government and the lack of resources.

"We need to change a lot of things, but our clients also come out and help," she said. "These volunteers work so hard. So I have no excuse."